Some people are born to be great explorers. Salomon August Andrée was not one of them. One of many explorers who attempted to claim the North Pole at the turn of the 20th century, Andrée is remembered, not for his success, but for his spectacular failure.

You see, Andrée wanted to fly a balloon to the edge of the map. But, before we get ahead of ourselves, we have to set the scene for this tale of hubris and ambition.

The Final Frontier

The late 19th century gave rise to a period known as the Heroic Age of Polar Expedition. The rest of the map had already been filled in; the Poles were the last great push any country could make for eternal glory. The Poles, not space, were the final frontier, and Andrée wanted to claim the North Pole for Sweden.

As a bonus, whoever reached the North Pole would likely discover the Northwest Passage, a mythical trade route from North America to Asia. The Passage was as elusive as it was deadly. It would be a worthy consolation prize if Andrée failed to land on the Pole.

Previous attempts at reaching the Pole had been disastrous to say the least. Ships were destroyed, scurvy carved threw crews like a hot knife through butter, and more than 200 lives had already been lost in the quest for the Pole.

Ships were subject to the whims of the ice. Hauling sledges was absolutely brutal on the crew. Why not try sailing a hydrogen balloon?

Sweden's progress was next to nothing in terms of polar exploration. This was extra embarrassing as their politically subordinate neighbor, Norway, was leading the pack. If Sweden wanted to claim the Pole, they had to act fast.

An Amateur Aeronaut

Gustaf Vilhelm Emanuel Swedenborg on Wikimedia

Gustaf Vilhelm Emanuel Swedenborg on Wikimedia

Enter S. A. Andrée. On paper, Andrée was the ideal candidate for an expedition. He was a scientist with a keen interest in aeronautics and previous experience living and working in the Arctic Circle. Andrée was also a persuasive speaker who managed to get Alfred Nobel and King Oscar II on board.

Funding and crew secured, Andrée approached his project with a near-delusional level of optimism. This was where the problems started. Andrée was, for all intents and purposes, Sweden's first balloonist; nobody in his inner circle knew any better to question him.

Andrée's expectations for the expedition were full of more hot air than his balloon. He assumed he could simply fly over a polar desert, drop a buoy, and claim eternal glory. When experienced balloonists explained their concerns, he refused to listen.

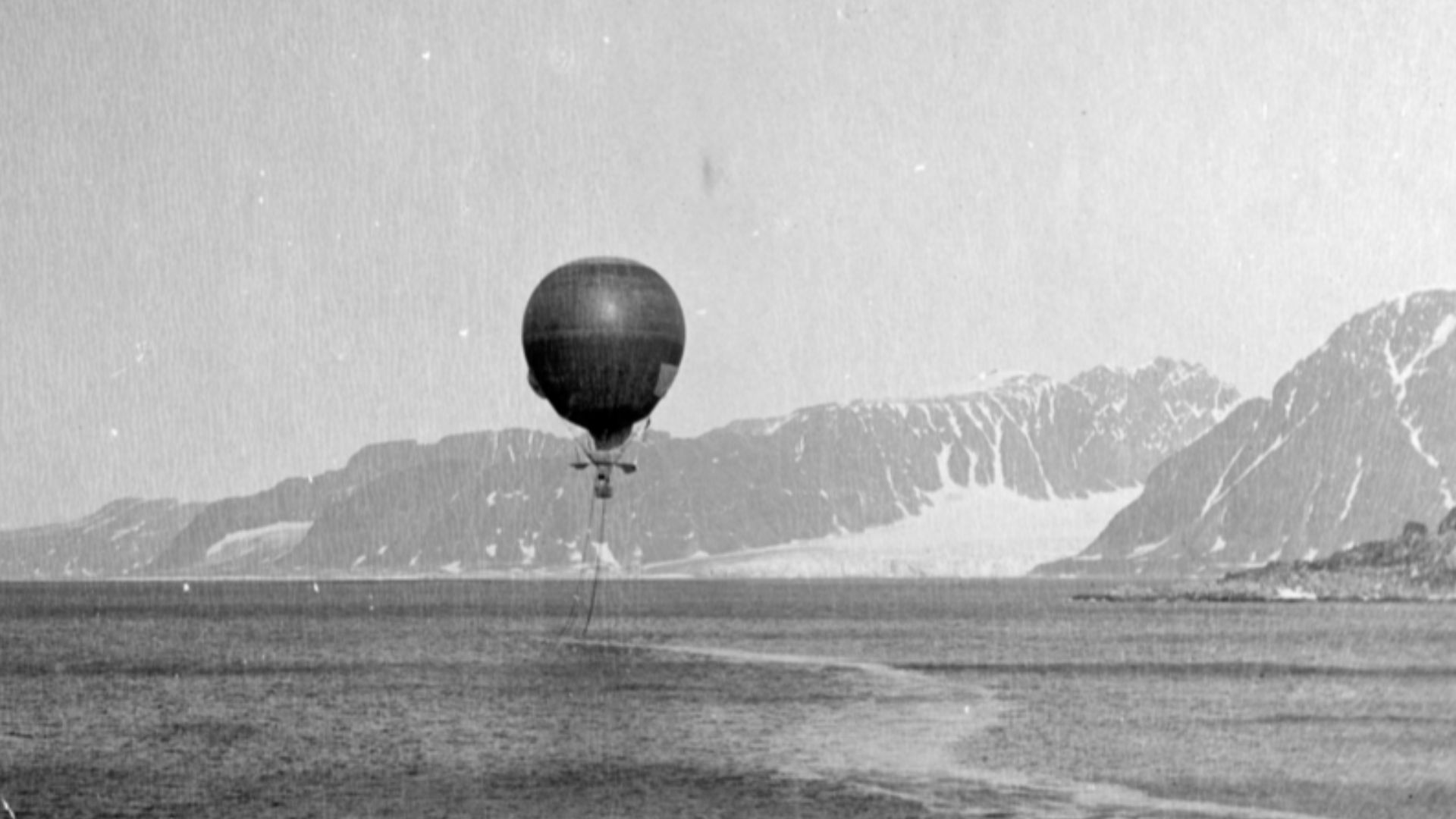

Andrée commissioned a custom balloon named the Eagle. Unfortunately, the balloon was better suited for a sedate voyage over the countryside than the unforgiving Arctic. And that was without getting into the crew's lack of survival skills.

Undeterred, Andrée and his companions took to the skies in summer 1896. The Eagle had not been tested prior to take-off; safety and technical issues quickly became apparent. This initial attempt was, as you may imagine, a colossal failure.

What Comes Up Must Come Down

Despite being labeled a fraud, Andrée persisted with his idea, trying again the following summer. On July 1897, S. A. Andreé, engineer Knut Fraenkel, and photographer Nils Strindberg made lift-off. They were never seen again.

Problems arose almost immediately. First, they lost steering capabilities; then, they were caught in a windstorm; then, they crashed. Instead of flying for a month as planned, they were airborne for only two days.

When they crashed, the men were aware that they would never reach the Pole. Their new objective was to return to civilization. Unfortunately, their landing supplies were not chosen with much care.

Miraculously, the men survived for three months, hauling sledges across uneven ice in the middle of nowhere. Despite their lack of survival skills, they had good luck with hunting, and the fresh meat from seals and polar bears helped stave off scurvy.

The exact cause of death is still unknown over a century later. Exposure, overdose (they carried opium and morphine with them), and a parasitic infection from undercooked meat are all given as potential factors.

The wreck of the Eagle along with the remnants of the crew's final resting place were discovered in 1930. Their stunted progress and grueling final days were meticulously documented in diary entries and photographs. Their bodies were returned to Sweden, where they were regarded as martyrs for science.

KEEP ON READING

The Clueless Crush: How I Accidentally Invited a Hacker Into…

Fluorescent Lights and First Impressions. My name is Tessa, I'm…

By Ali Hassan Nov 4, 2025

The History Of Your Favorite Dog Breeds

Hannah Lim on UnsplashFrom vicious wolves to our furry friends,…

By Breanna Schnurr Nov 13, 2025

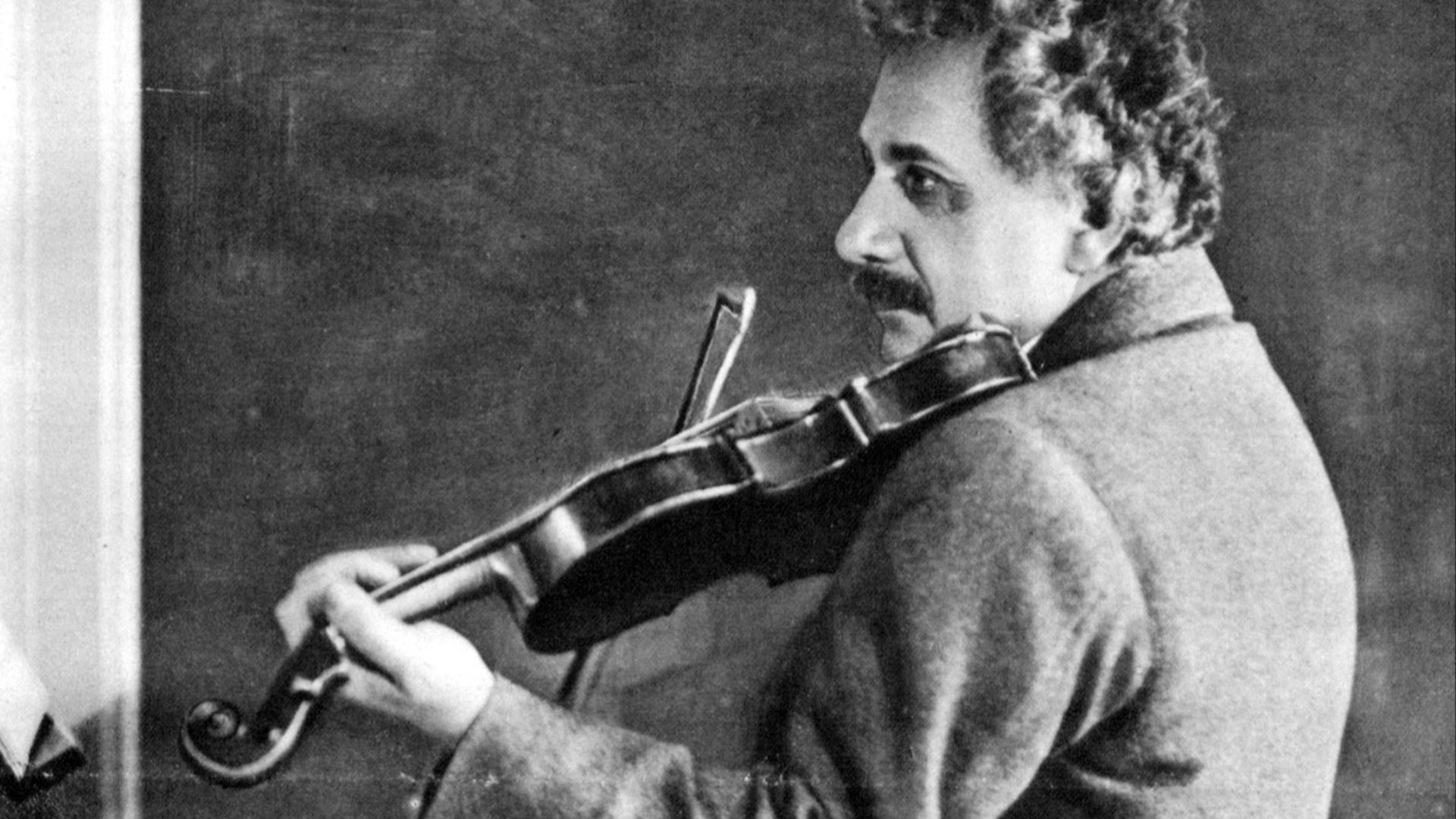

Einstein's Violin Just Sold At An Auction—And It Earned More…

A Visionary's Violin. Wanda von Debschitz-Kunowski on WikimediaWhen you hear…

By Ashley Bast Nov 3, 2025

The Mysterious "Sea People" Who Collapsed Civilization

3,200 years ago, Bronze Age civilization in the Mediterranean suddenly…

By Robbie Woods Mar 18, 2025

20 Inventors Who Despised Their Creations

Made It… Then Hated It. Inventors often dream big, but…

By Chase Wexler Aug 8, 2025

20 Incredible Items In The British Museum People Say Were…

Mystery In History. The mighty halls of the British Museum…

By Chase Wexler Sep 8, 2025