When archaeologists discuss ancient Chinese civilization, the conversation typically gravitates toward the famous Shang, Qin, or Tang dynasties. There's another fascinating culture that doesn't get nearly enough attention, though, and it thrived in what's now central China around 1600 to 1400 BCE. The Erlitou culture gets its share of academic focus, and the Sanxingdui site has become something of a media sensation in recent years with its bizarre bronze masks, but sandwiched between these better-known civilizations were the Erligangs, a Bronze Age culture that left behind remarkable evidence of sophisticated metalworking, massive urban planning, and what might've been one of ancient China's earliest attempts at territorial expansion.

The Erligang culture takes its name from a type site discovered in 1951 near Zhengzhou, Henan Province, where excavations revealed a massive walled city that would've been one of the largest urban centers of its time anywhere in the world. What makes this culture particularly intriguing is how it represents a transitional period in Chinese history, potentially bridging the gap between the legendary Xia Dynasty and the historically verified late Shang Dynasty. Archaeological evidence suggests the Erligang culture wasn't just a local phenomenon but rather an expansive civilization that influenced a huge swath of ancient China, reaching as far south as the Yangtze River valley through trade networks, military outposts, or cultural exchange.

The Discovery and Massive Scale of Erligang Sites

Prof. Gary Lee Todd on Wikimedia

Prof. Gary Lee Todd on Wikimedia

The primary Erligang site at Zhengzhou was discovered in 1951, though the significance of what archaeologists had found took time to be fully appreciated. Early excavations revealed bronze vessels, pottery, and architectural remains that seemed stylistically distinct from both earlier Erlitou finds and later Shang artifacts from Anyang. Researchers realized they'd found part of a substantial city wall in 1955 during surveys of Zhengzhou, and local archaeologists gradually understood the scale of what lay beneath the modern city. After decades of careful study and radiocarbon dating, scholars now generally place the Erligang culture between approximately 1600 and 1400 BCE, making it contemporary with what traditional Chinese histories describe as the early Shang Dynasty.

The city of Zhengzhou was enclosed by massive rammed-earth walls with a perimeter of about seven kilometers. Archaeologists estimate these walls would've been 20 meters wide at the base and originally rose to heights of eight meters, representing an enormous investment of labor that suggests a highly organized society capable of mobilizing thousands of workers for large-scale public projects. The rammed-earth construction technique involved packing layers of earth so tightly that sections have survived for over three millennia. Inside these walls, large workshops were discovered outside the city walls, including a bone workshop, a pottery workshop, and two bronze vessel workshops, indicating specialized craft production on an industrial scale.

Beyond Zhengzhou, archaeologists have identified Erligang-style artifacts and architectural features at sites scattered across central China. In its early years, the culture expanded rapidly, reaching the Yangtze River, and then gradually shrank from its early peak. This geographic distribution has sparked considerable debate about whether the Erligang culture represented a single political entity, a trading network, or perhaps multiple related chiefdoms that shared cultural practices and technological innovations. Some sites show evidence of local adaptations of Erligang material culture, suggesting that the relationship between the core area and peripheral regions was complex and probably involved varying degrees of political control, economic exchange, and cultural influence.

Bronze Technology and Artistic Achievement

What really sets the Erligang culture apart is its advanced bronze metallurgy, which represents a significant technological leap from earlier Chinese Bronze Age cultures. Erligang was the first archaeological culture in China to show widespread use of bronze vessel castings, and bronze vessels became much more widely used and uniform in style than at Erlitou. The bronzes produced during this period include ritual vessels like ding tripods, jue wine vessels, and gui food containers that feature elaborate designs incorporating animal motifs, geometric patterns, and occasionally taotie masks with their characteristic large eyes and frontal animal faces. These weren't just functional objects but rather items imbued with ritual significance, likely used in ceremonies related to ancestor worship or communication with spiritual powers.

Chinese bronze workers used piece-mold casting techniques, where clay section molds of two or more parts were assembled around a core. This technique involved the use of clay models and complicated piece molds, which were never reused, meaning every vessel was made from an original clay model and an original mold. This method allowed artisans to create complex shapes and intricate surface decorations that would've been impossible with simpler techniques, and it represented a distinctly Chinese approach that differed dramatically from the lost-wax methods used in the Middle East and Europe. The quality and quantity of bronze production during the Erligang period suggest that metalworkers had achieved a level of expertise that required years of training and experimentation, with specialized foundries producing bronzes on what scholars have described as an industrial scale.

The earliest form of the taotie motif on bronzeware, dating from early in the Erligang period, consists of a pair of eyes with some subsidiary lines, and the motif was soon elaborated as a frontal view of a face with oval eyes and mouth. Erligang bronzes show both continuity with earlier Erlitou traditions and innovations that would influence later Shang Dynasty styles. Certain vessel forms and decorative motifs can be traced back to Erlitou prototypes, while other features appear to be Erligang innovations that became standard elements in later Chinese bronze art. This pattern of technological and artistic development supports the interpretation of the Erligang culture as a crucial bridge between earlier Bronze Age societies and the mature civilization that would eventually flourish at Anyang during the late Shang Dynasty.

Territorial Expansion and Resource Networks

Ismoon (talk) 18:54, 16 July 2014 (UTC) on Wikimedia

Ismoon (talk) 18:54, 16 July 2014 (UTC) on Wikimedia

The archaeological evidence reveals that securing metal resources was likely a driving force behind the Erligang expansion. The large site at Panlongcheng, on the Yangtze River in Hubei, is currently the largest excavated site associated with the Erligang culture, discovered in 1954 and excavated in 1974 and 1976. Panlongcheng is located approximately 500 kilometers south of Zhengzhou and shows the southernmost reach of the Erligang culture at its peak. Since Zhengzhou lacked direct access to copper and tin deposits needed for bronze production, archaeologists have long theorized that southern sites like Panlongcheng functioned as resource extraction outposts. Carbon dating of wood samples from copper mines at Tonglu Mountain in Hubei showed that the mineral elements of Panlongcheng bronzes were the same as those from Tonglushan, indicating that copper originated from these mines.

The expansion and retraction of Erligang culture appears to have taken place over about 200 years, and this rapid rise and fall, together with the assumed need to secure natural resources, has been taken as evidence for a military occupation and an empire model. The tombs and bronzes at Panlongcheng closely resemble those at Zhengzhou, with elite burials containing bronze ritual vessels, jade objects, and even human sacrificial victims that demonstrate the wealth and status of the upper classes. The construction and bronze casting techniques at Panlongcheng are identical to the techniques employed at Zhengzhou, though the pottery style is different, suggesting that while metalworking remained standardized across the Erligang world, local populations maintained some cultural autonomy.

More recent scholarship has proposed alternative explanations for the Erligang expansion beyond simple military conquest. Some researchers suggest models of local lordships, trade diaspora, or ritual landscapes rather than direct imperial control. At distant sites, local populations appear to have adopted Erligang bronze casting techniques while maintaining their own pottery styles and burial customs, suggesting selective cultural borrowing rather than wholesale domination. Understanding these patterns of interaction helps illuminate how complex societies emerged and spread in ancient China, creating the foundations for later imperial civilizations that would dominate East Asia for millennia.

KEEP ON READING

The story of Ching Shih, the Woman Who Became the…

Unknown author on WikimediaFew figures in history are as feared…

By Emilie Richardson-Dupuis Dec 29, 2025

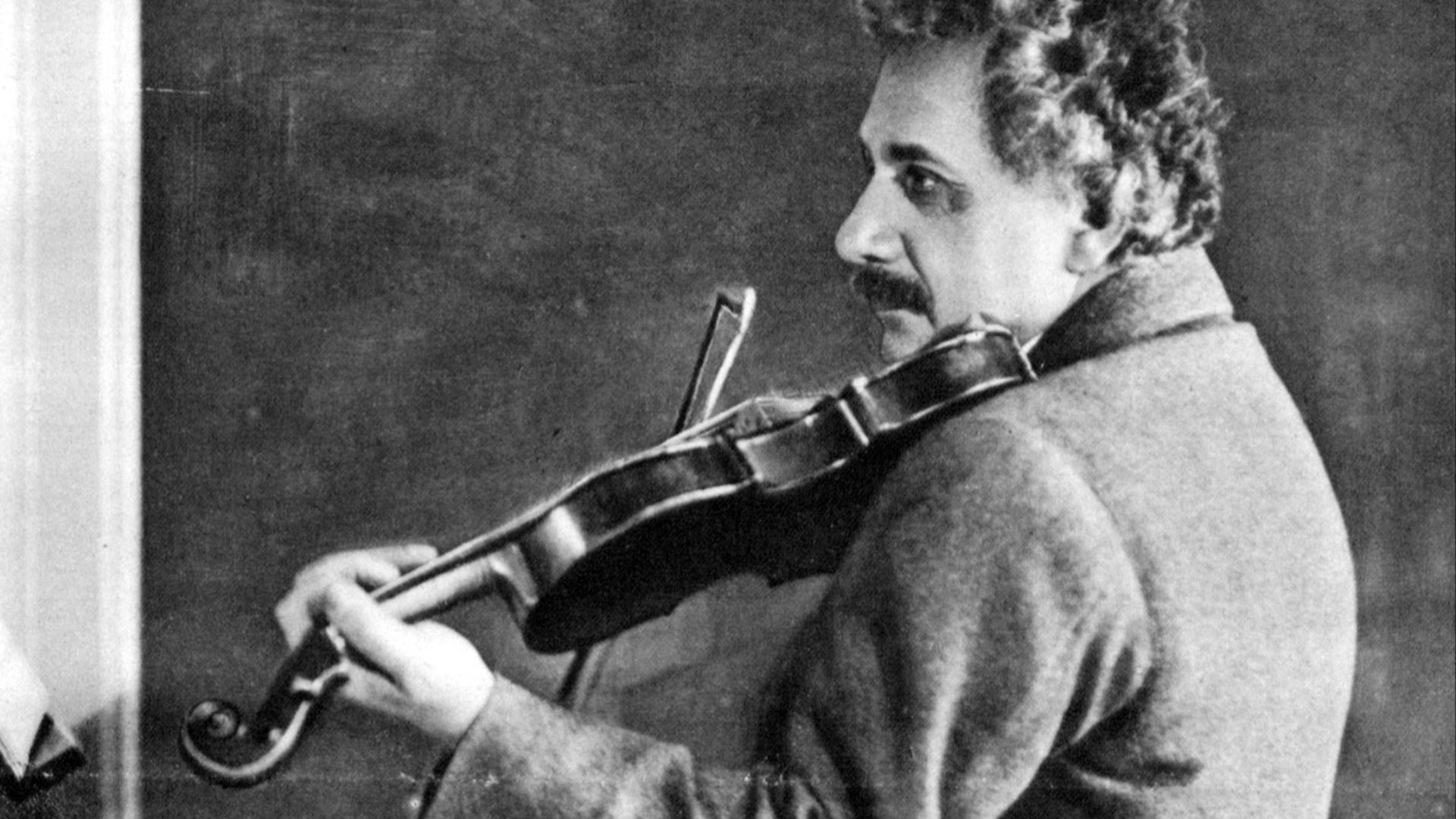

Einstein's Violin Just Sold At An Auction—And It Earned More…

A Visionary's Violin. Wanda von Debschitz-Kunowski on WikimediaWhen you hear…

By Ashley Bast Nov 3, 2025

This Infamous Ancient Greek Burned Down An Ancient Wonder Just…

History remembers kings and conquerors, but sometimes, it also remembers…

By David Davidovic Nov 12, 2025

The Mysterious "Sea People" Who Collapsed Civilization

3,200 years ago, Bronze Age civilization in the Mediterranean suddenly…

By Robbie Woods Mar 18, 2025

20 Inventors Who Despised Their Creations

Made It… Then Hated It. Inventors often dream big, but…

By Chase Wexler Aug 8, 2025

20 Commanders Who lost Control Of Their Own Armies

When Leaders Lose Their Grip. Control is what makes a…

By Sara Springsteen Feb 5, 2026