Doing Our Best To Understand

When a written language stops being read, surviving texts can’t be understood without a translation method. Decipherment compares signs, sounds, and repeated phrases, often using bilingual inscriptions as a guide. Unfortunately, for some of these languages, we’ve yet to be able to bridge that language gap.

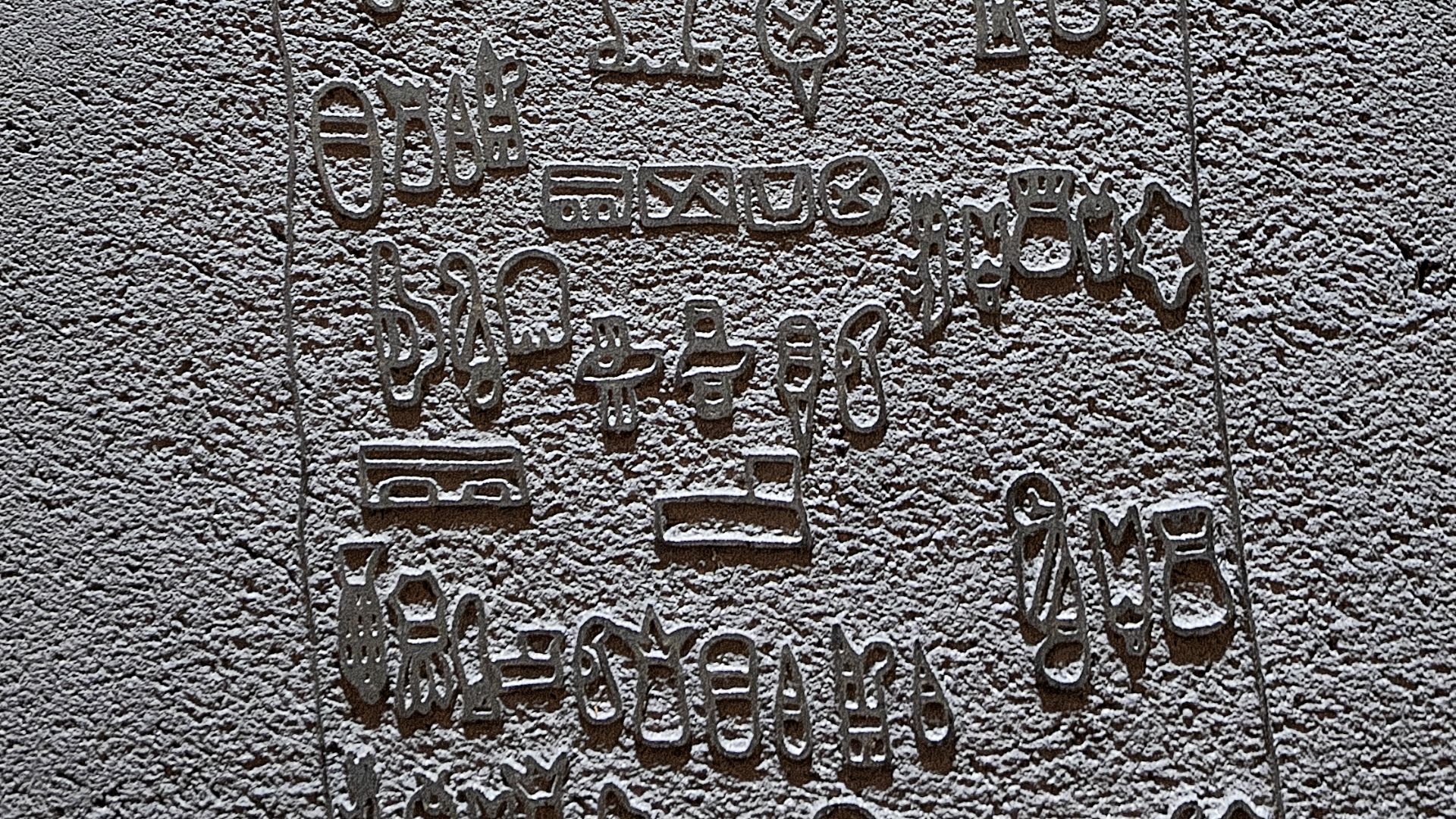

The Cleveland Museum of Art on Unsplash

The Cleveland Museum of Art on Unsplash

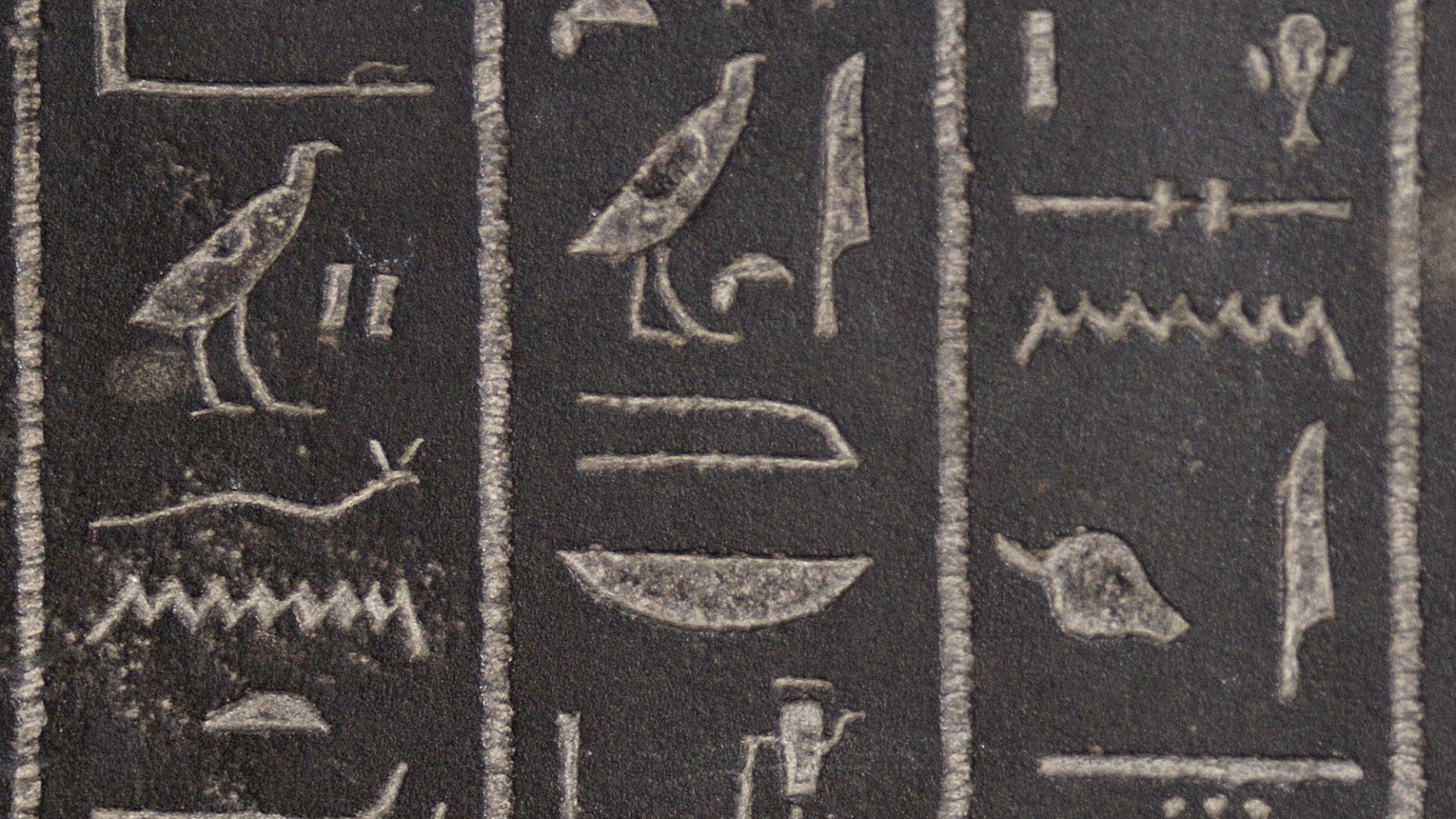

1. Egyptian Hieroglyphs

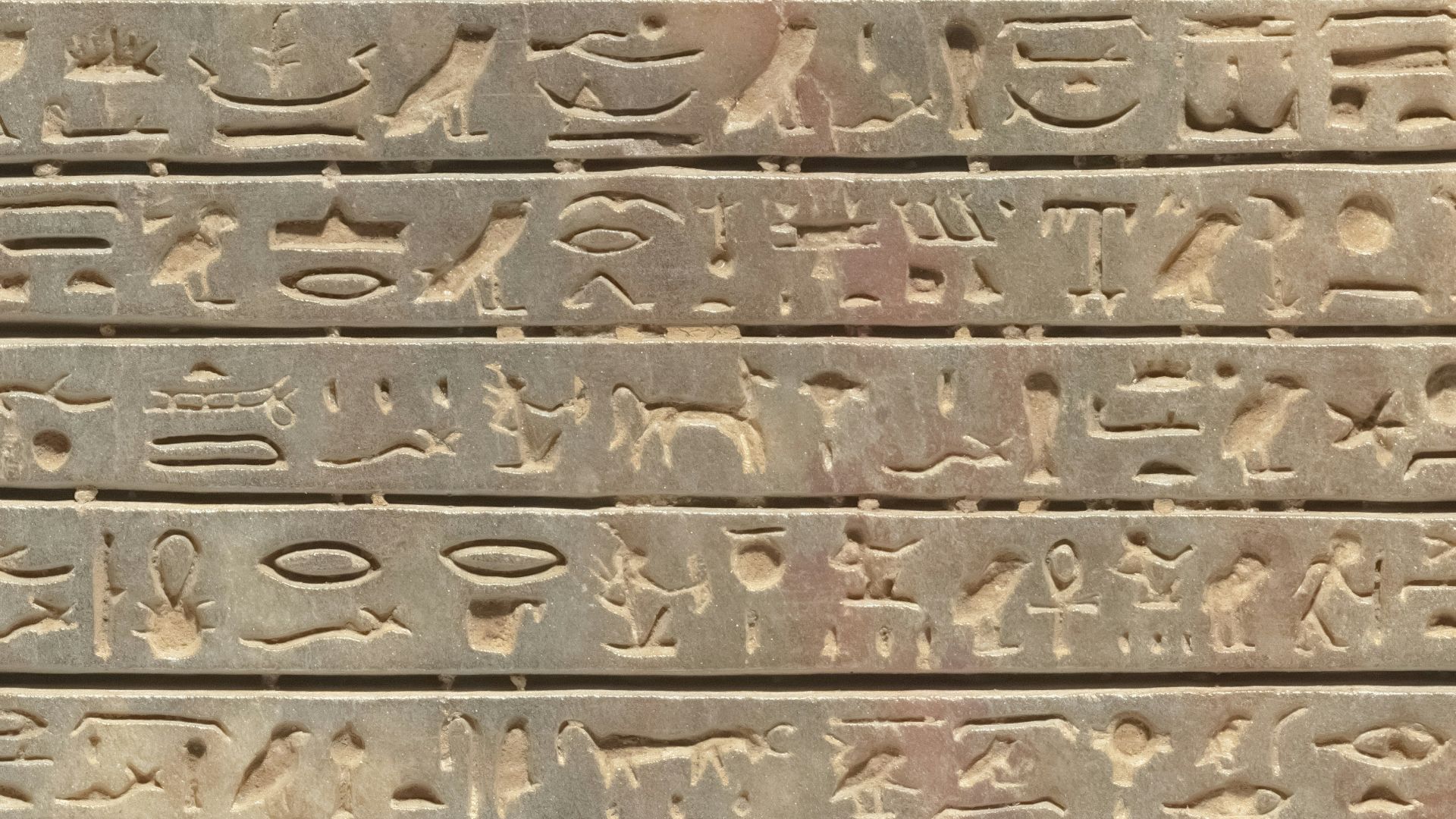

Hieroglyphs were used across ancient Egypt, but later readers couldn’t interpret them once the tradition ended. In 1822, Jean-François Champollion announced and explained core phonetic principles using the Rosetta Stone and related evidence. After that, longer religious and historical texts became translatable.

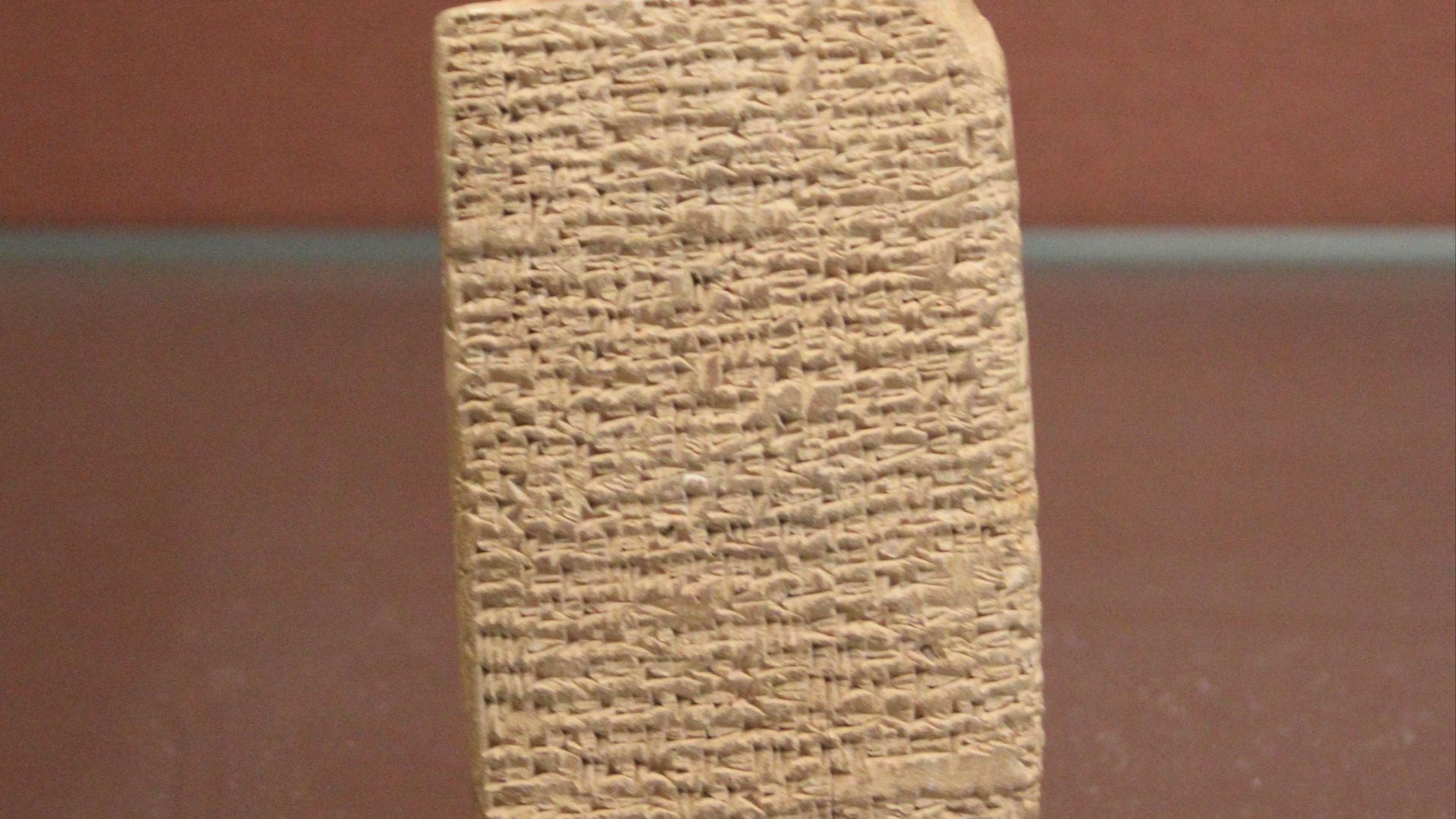

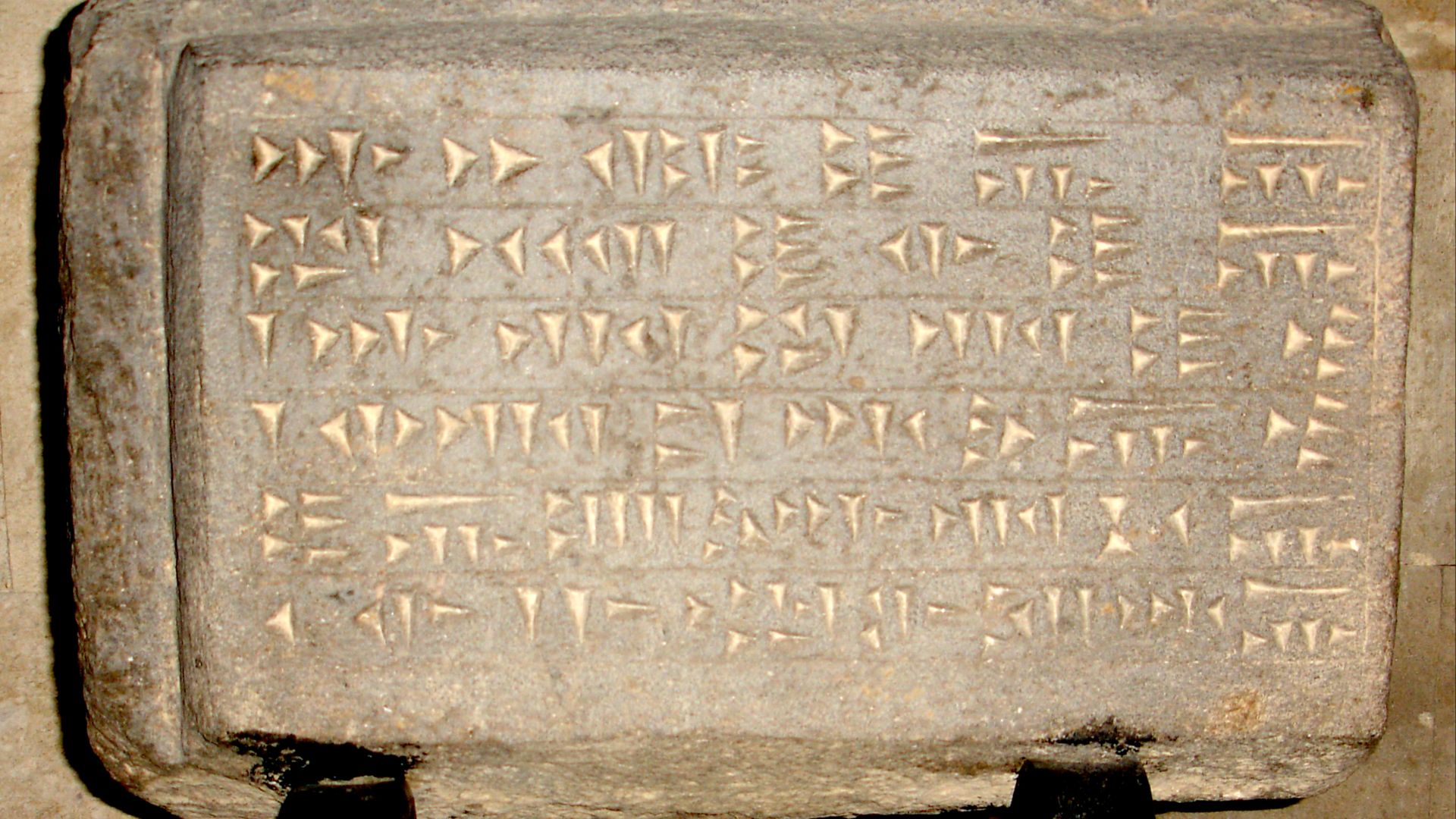

2. Old Persian Cuneiform

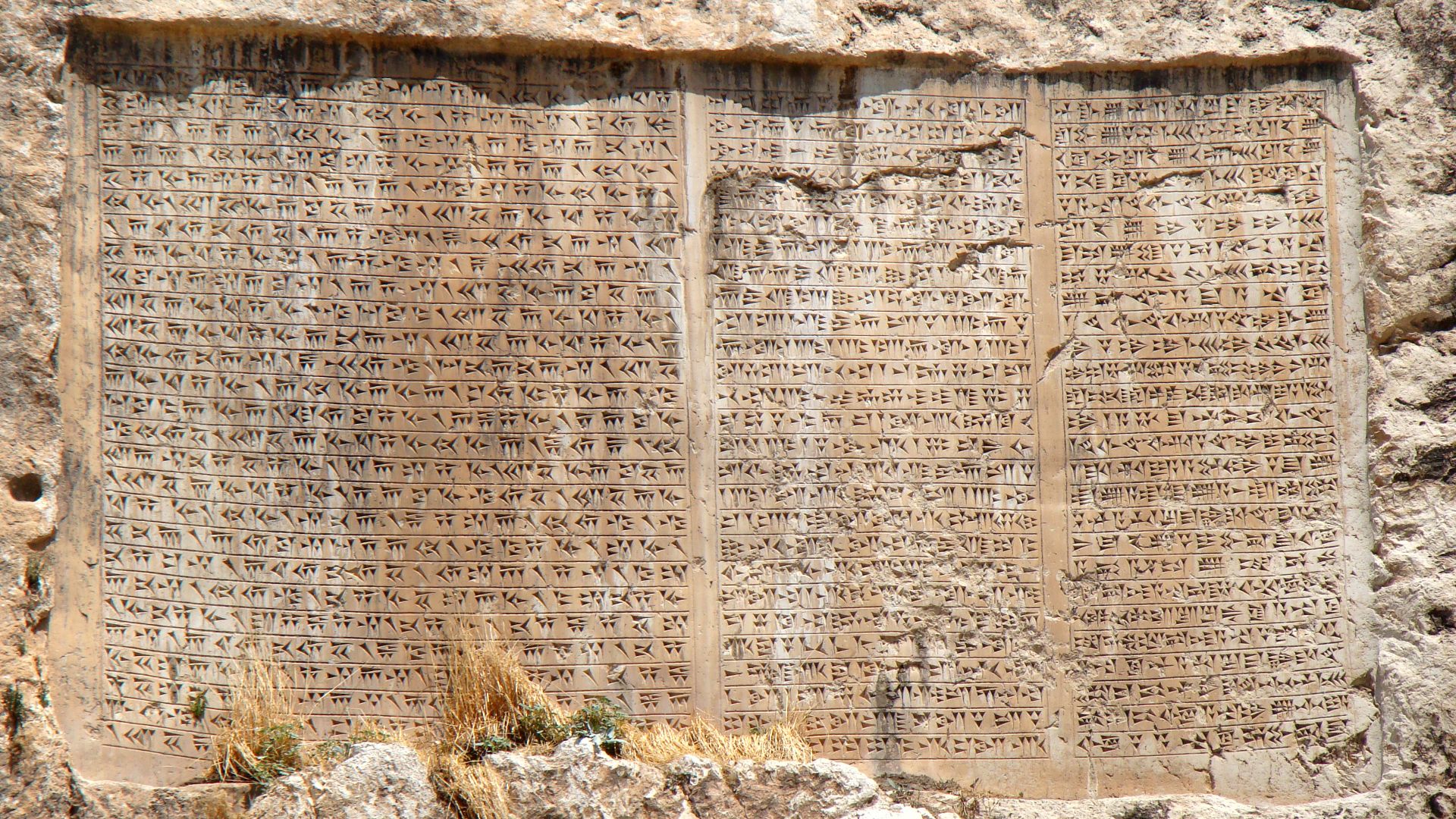

Old Persian appears on Achaemenid royal inscriptions and uses a relatively small sign set. Georg Friedrich Grotefend made a breakthrough in 1802 by matching repeated patterns to known royal names and titles. Henry Rawlinson’s work on the trilingual Behistun inscription later confirmed readings and supported broader cuneiform study.

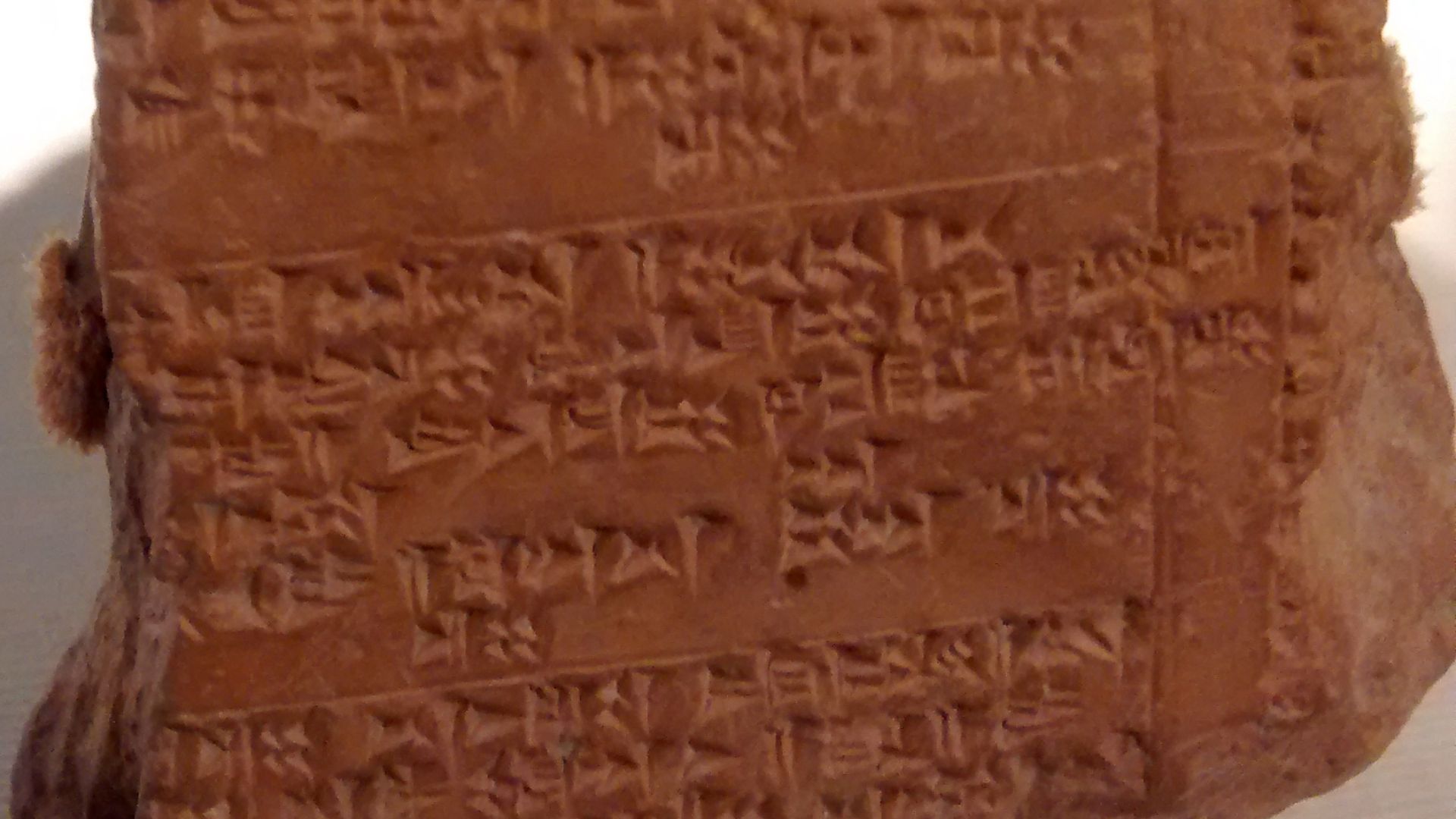

3. Akkadian Cuneiform

Akkadian was written with cuneiform signs that can be tricky because one sign may have multiple values. In 1857, the Royal Asiatic Society asked four scholars to translate the same Assyrian text independently and then compare their sealed results. The close agreement helped convince the public that Akkadian cuneiform had been deciphered.

Bjørn Christian Tørrissen on Wikimedia

Bjørn Christian Tørrissen on Wikimedia

4. Sumerian

Sumerian texts were written in cuneiform and preserved in scribal schools alongside Akkadian, which is why bilingual word lists survived. Researchers recognized a non-Semitic layer in the 1800s, and Jules Oppert identified it in 1869 as the Sumerian language. Those bilingual tablets then helped scholars develop grammar and vocabulary over time.

5. Hittite

Clay tablets from Hattusa revealed the Hittites’ laws, treaties, and royal letters, but the language was unknown at first. In 1915, Bedřich Hrozný published a breakthrough showing that Hittite was Indo-European and offered workable readings. That made it possible to study Hittite diplomacy in the Bronze Age.

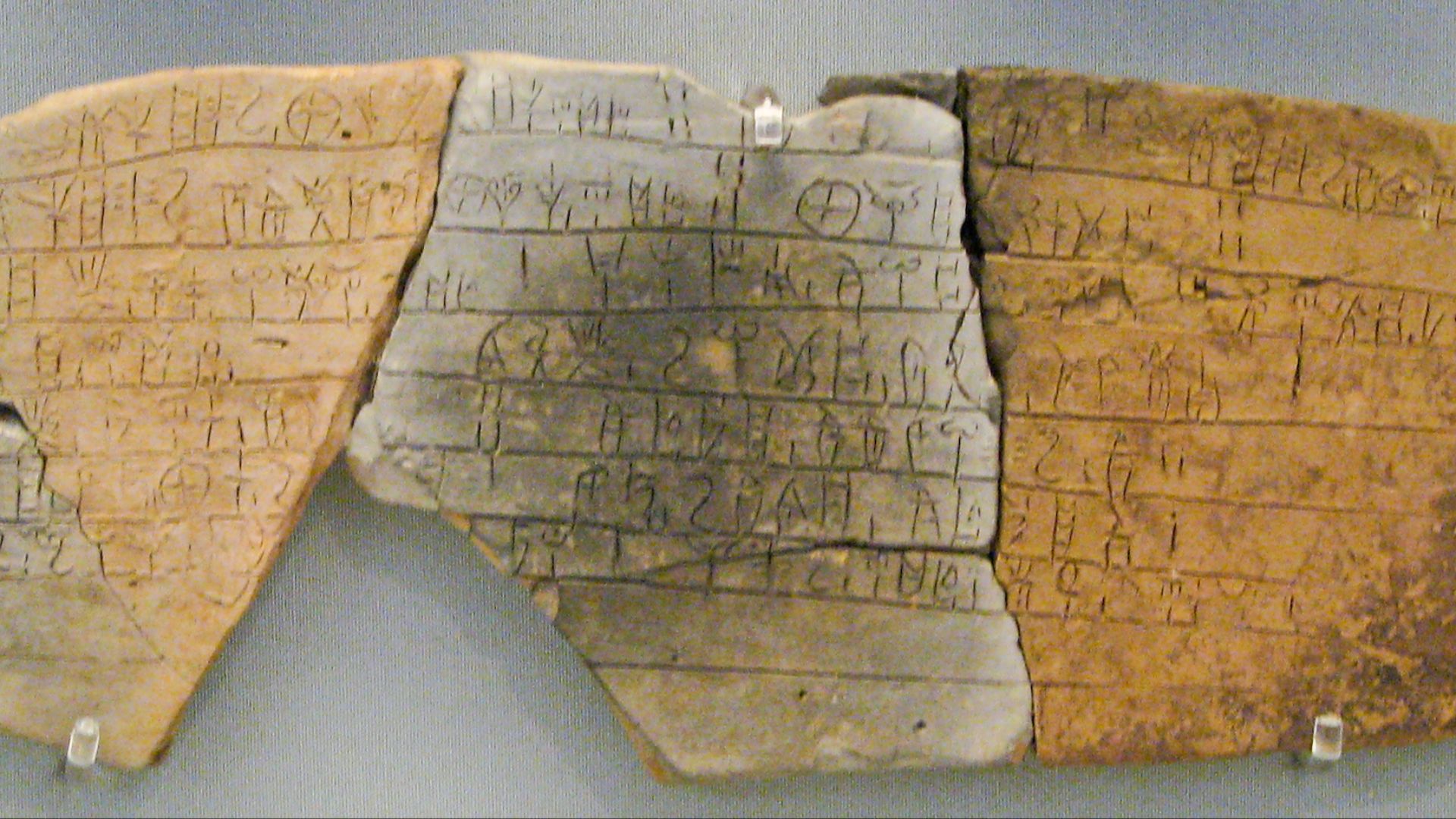

6. Linear B

Linear B tablets come from Mycenaean palaces and mostly track supplies, land, and workers. In 1952, Michael Ventris demonstrated that the script recorded an early form of Greek, with John Chadwick helping strengthen the linguistic case soon after. You can now read many tablets and see how palace administrations operated.

7. Ugaritic

Ugaritic was found at ancient Ugarit in Syria, written in an alphabetic cuneiform script rather than the usual syllabic system. By 1930, scholars including Hans Bauer, Edouard Dhorme, and Charles Virolleaud had deciphered enough signs to read the tablets. Their progress made myths, rituals, and letters from Ugarit accessible.

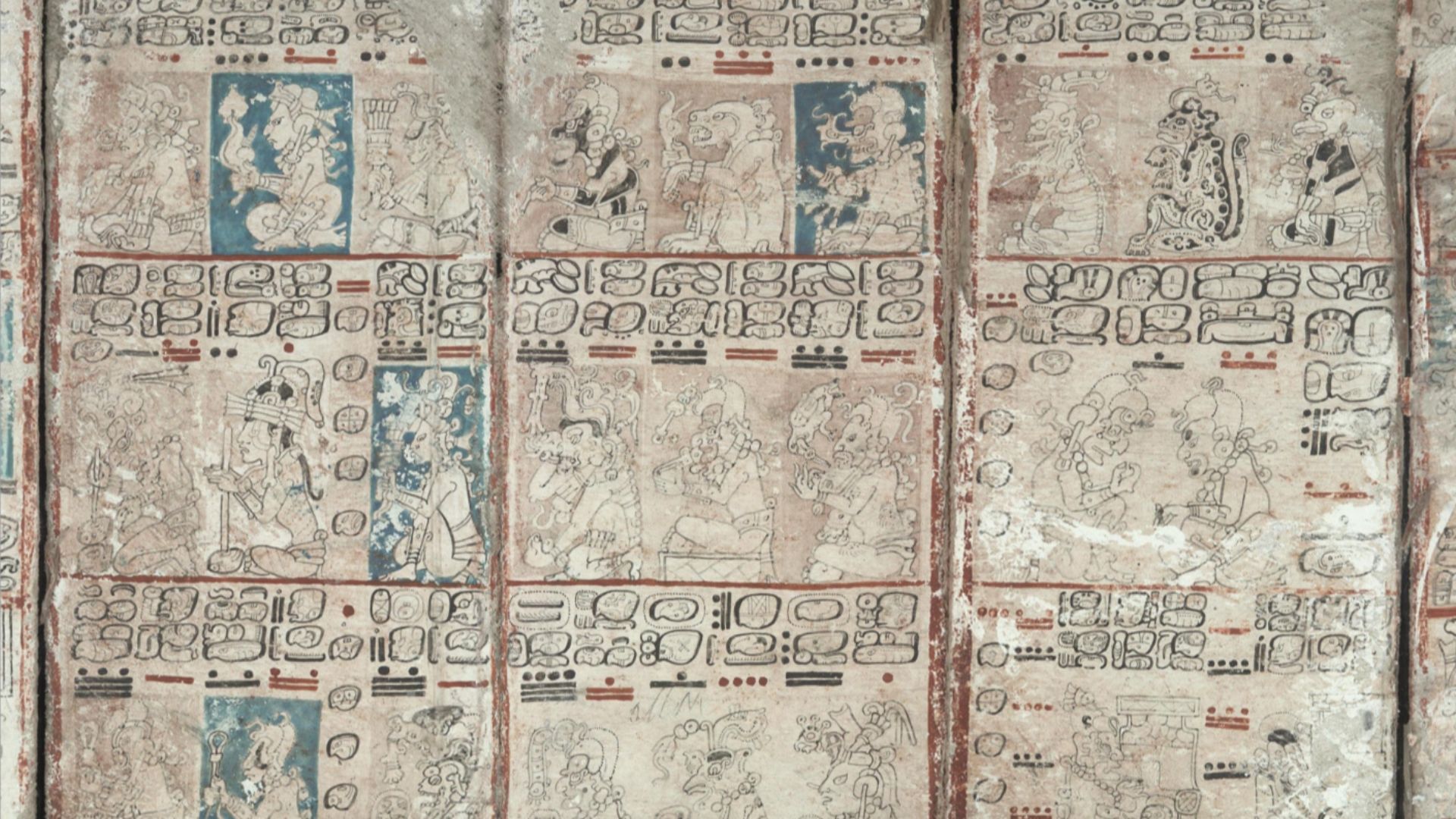

8. Maya Script

Maya writing mixes sound-based and meaning-based signs and appears on monuments and a few surviving books. In 1952, Yuri Knorozov argued for phonetic readings, and later researchers built on that approach across many inscriptions. Today, you can follow rulers, wars, and alliances through Maya texts.

Unknown authorUnknown author on Wikimedia

Unknown authorUnknown author on Wikimedia

9. Lycian

Lycian was spoken in southwestern Anatolia and written with a Greek-related alphabet plus extra letters. Scholars made tentative progress in the 1830s using short Lycian-Greek bilingual texts. Real advances came toward the end of the 1800s, which is why translations became far more consistent.

Laszlovszky András at Hungarian Wikipedia after Unicode Standard on Wikimedia

Laszlovszky András at Hungarian Wikipedia after Unicode Standard on Wikimedia

10. Urartian

Urartian was used around Lake Van and survives mainly in official inscriptions written with cuneiform. In 1882, Archibald H. Sayce published a major decipherment and translation of the “Van” inscriptions. Later discoveries refined readings and expanded what could be translated.

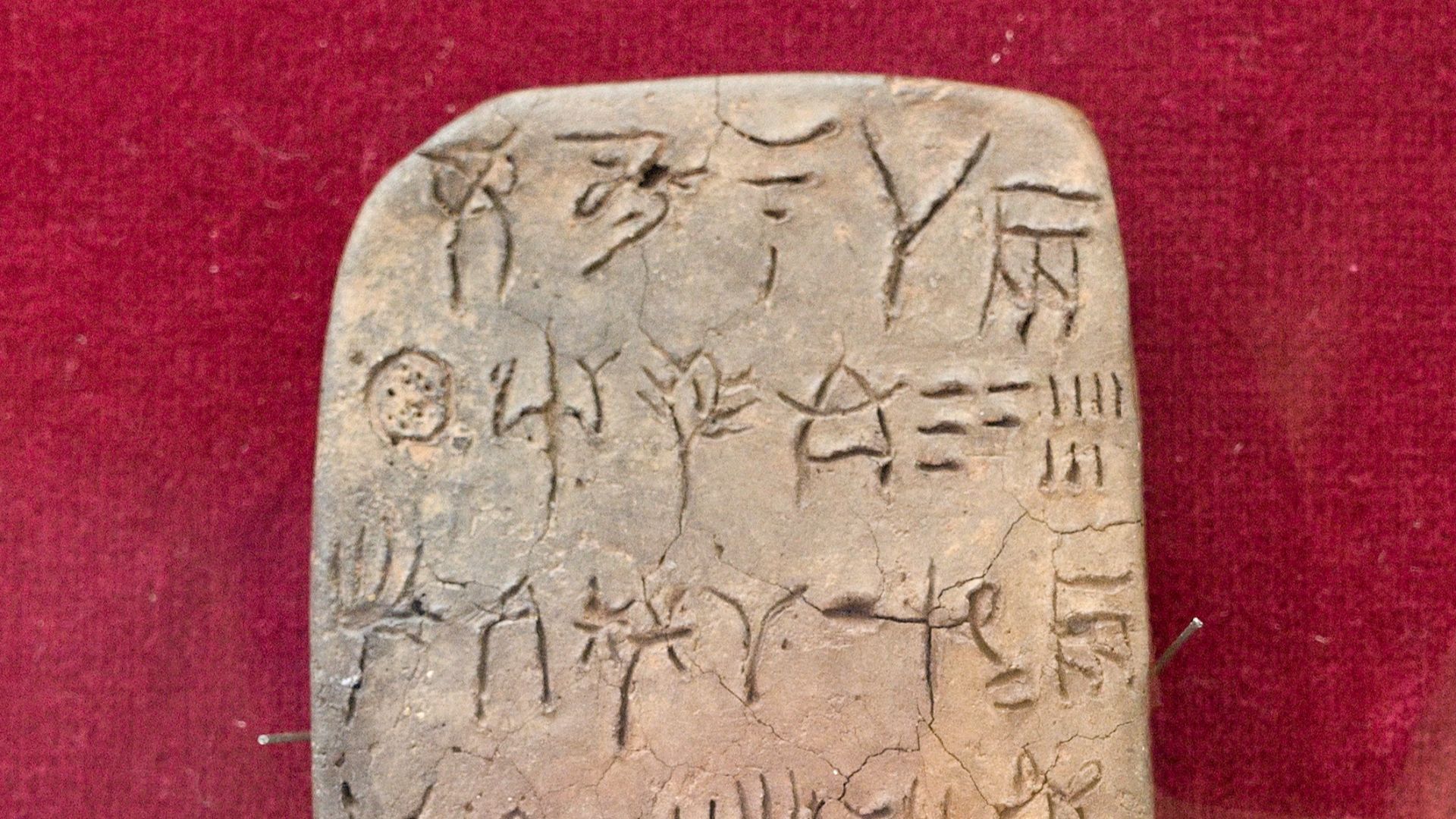

1. Indus Script

The Indus script comes from the Indus Valley Civilization in what’s now Pakistan and northwest India. Most inscriptions are extremely short, often appearing on seals, so there’s not enough text to confidently identify grammar or vocabulary. Researchers keep building sign lists and testing theories, but the lack of a bilingual text and the unknown underlying language continue to block consensus.

PHGCOM IndusValleySeals.JPG on Wikimedia

PHGCOM IndusValleySeals.JPG on Wikimedia

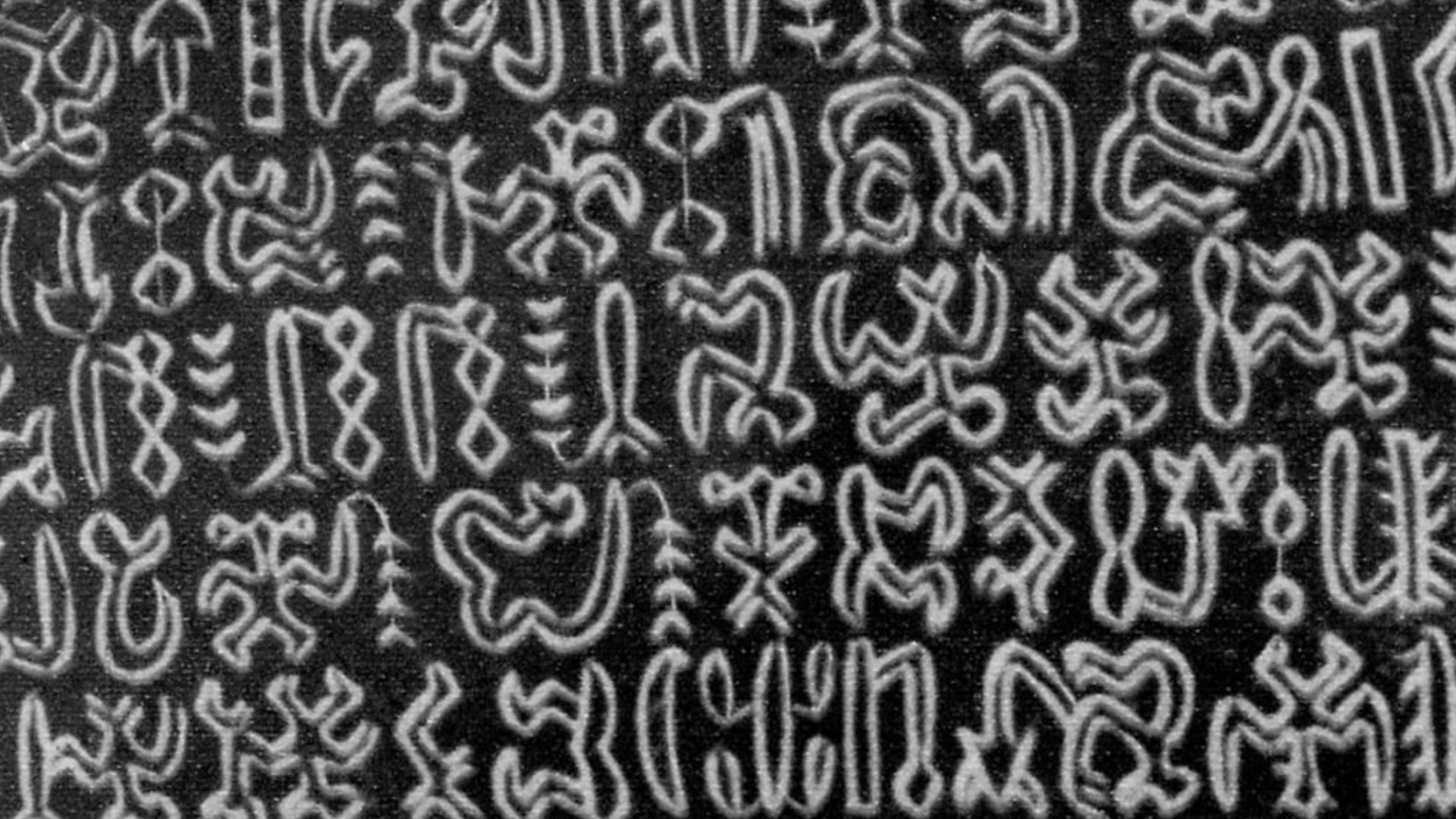

2. Rongorongo

Rongorongo is a set of carved glyphs from Rapa Nui (Easter Island), preserved mainly on wooden tablets and other objects. Many pieces were lost or destroyed in the nineteenth century, which means today’s corpus is small and often damaged. Scholars have cataloged signs, compared repeated sequences, and debated reading direction, yet there’s still no widely accepted way to turn the glyphs into readable sentences.

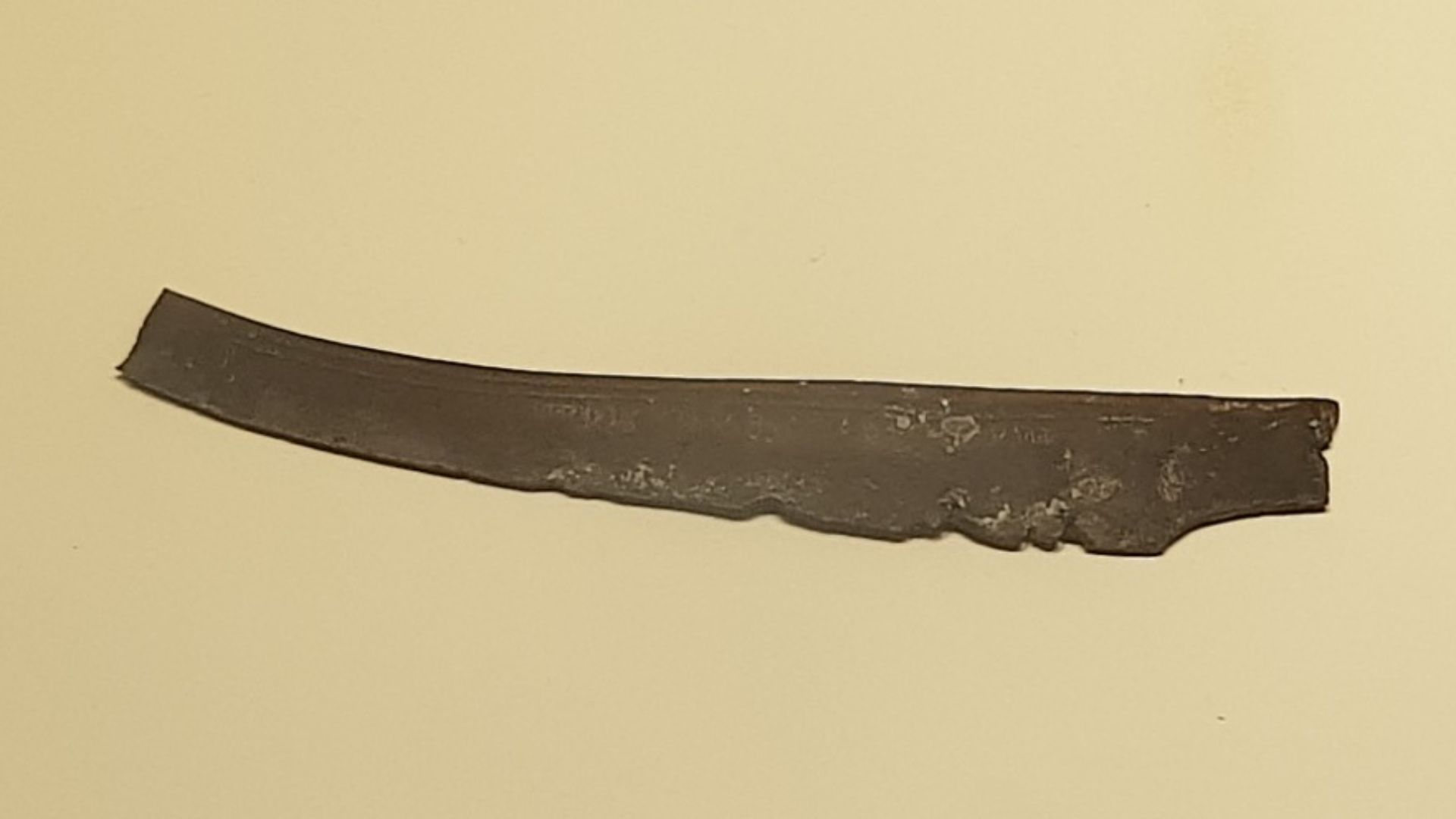

3. Linear A

Linear A was used by the Minoans on Crete and nearby islands during the Bronze Age. Even though many signs resemble Linear B, and approximate sound values can be suggested, the language underneath does not match known Greek or other well-documented tongues. Because most surviving texts look like administrative records, you’re stuck with repetitive accounting that doesn’t offer much context for translation.

4. Cretan Hieroglyphs

Cretan hieroglyphs appear on seals, sealings, and tablets from early Minoan Crete. The script’s small body of texts makes it hard to prove whether signs represent sounds, whole words, or a mix of both. Academics use improved photography, standardized sign catalogs, and archaeological context to narrow options, but no interpretation has persuaded the field.

5. Phaistos Disc

The Phaistos Disc is a fired clay disc found at Phaistos on Crete in 1908, stamped with a spiral of repeating signs. Since it’s essentially a one-off artifact, researchers can’t compare it to a larger set of documents to confirm patterns. People have proposed many readings, but without additional examples, it’s still unclear what language it represents, or even whether it’s a true text.

6. Proto-Elamite

Proto-Elamite is an early writing system from ancient Iran, with many tablets found at Susa and a few other sites. Parts of the numerical system can be handled, but the non-numerical signs remain largely unread. Specialists are publishing clearer tablet images and refining sign lists, yet inconsistent scribal habits and the absence of a translation aid keep the core language out of reach.

7. Cypro-Minoan

Cypro-Minoan is an undeciphered script from Late Bronze Age Cyprus, also found at a few sites beyond the island. Its inscriptions appear on different object types, and scholars suspect multiple regional or chronological varieties, which complicates “one-size-fits-all” readings. Work tends to focus on sorting the corpus, comparing it to related Aegean scripts, and isolating repeated strings that might be names or titles.

Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China on Wikimedia

Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China on Wikimedia

8. Byblos Script

The Byblos script, sometimes called “pseudo-hieroglyphic,” is known from a small number of inscriptions found in Byblos, in modern Lebanon. The limited corpus, uncertain sign values, and unclear links to Egyptian or Semitic writing traditions make the script hard to place. Researchers keep revisiting old readings with better documentation and looking for parallels, but there still isn’t a dependable decoding method.

Vyacheslav Argenberg on Wikimedia

Vyacheslav Argenberg on Wikimedia

9. Cascajal Block

The Cascajal Block is a stone object from Veracruz, Mexico, associated with the Olmec world and often discussed as very early New World writing. A major complication is that it wasn’t recovered through controlled excavation, so dating and context have been debated. Even if you accept it as writing, the current evidence is thin, and scholars rely on imaging, material analysis, and cautious pattern study rather than translation claims.

10. Khitan Small Script

A Khitan small script was used in the Liao Empire (in parts of today’s northeast China) to write the now-extinct Khitan language. Many surviving texts are epitaphs and monumental inscriptions, which provide names and dates but not an easy bilingual key. Linguists keep compiling and rechecking the corpus, matching known historical references, and testing structural hypotheses, yet full reading and confident translation are still works in progress.

KEEP ON READING

10 Lost Languages We've Been Able To Decipher & 10…

Doing Our Best To Understand. When a written language stops…

By Elizabeth Graham Jan 28, 2026

10 Noble Knights Who Defined Chivalry & 10 Infamous Ones…

A Code With Consequences. Chivalry was a moving target, shaped…

By Cameron Dick Jan 28, 2026

20 Lesser-Known Mythical Creatures No One Ever Talks About

A Bestiary Beyond the Usual Suspects. Everyone’s heard of dragons…

By Annie Byrd Jan 28, 2026

20 Everyday Objects That Have a Surprisingly Dark History

When Familiar Objects Carry Uncomfortable Origins. Everyday objects feel neutral…

By Rob Shapiro Jan 28, 2026

Pooches Of The Past: Extinct Dog Breeds

Unknown authorUnknown author on WikimediaDogs have been showing up in…

By Elizabeth Graham Jan 27, 2026

20 Brilliant Inventors Who Made Others Rich And Died Poor

Genius Doesn’t Always Pay the Bills. History likes to remember…

By Sara Springsteen Jan 27, 2026