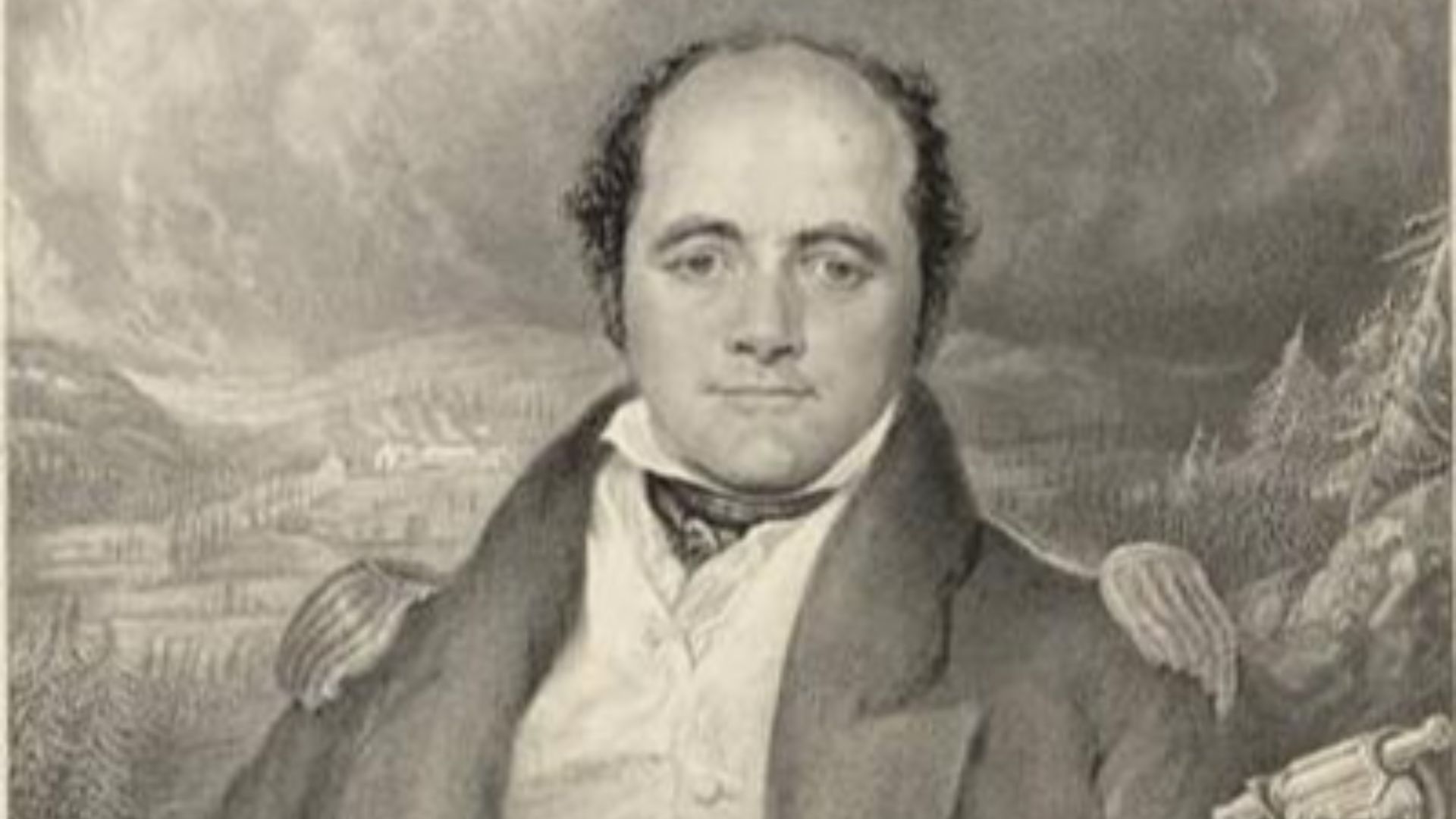

The history of Arctic exploration reads like a catalog of human suffering, but few stories capture the desperation of survival quite like John Franklin's first overland expedition. Before Franklin became famous for his doomed final voyage in search of the Northwest Passage, he earned the nickname "the man who ate his boots" during an 1819-1822 expedition across northern Canada. The moniker wasn't metaphorical. When provisions ran out and the land offered nothing, Franklin and his men literally boiled and consumed their leather footwear to avoid starvation.

This wasn't romantic adventure. The expedition deteriorated into a nightmare of starvation, murder, and possible cannibalism that killed 11 of the 20 men who set out. Franklin survived, but only barely, and only through measures that stripped away any pretense of civilized dignity. The boot-eating incident became a defining moment in the annals of polar exploration, representing both the extreme lengths humans will go to survive and the catastrophic failures of preparation that made such extremes necessary.

A Mission Built on Optimism and Ignorance

Franklin's 1819 expedition set out from England with the goal of mapping the northern coast of Canada and reaching the polar sea. The Royal Navy dispatched Franklin with instructions to chart unknown territory and advance British claims in the Arctic. Naval leadership assumed the expedition would rely on British supply lines supplemented by local resources and indigenous knowledge.

The optimism proved wildly misplaced. Franklin and his men knew virtually nothing about survival in the subarctic wilderness. They brought inadequate supplies for the journey's length and difficulty. The expedition relied heavily on pemmican and other provisions they expected to obtain from Hudson's Bay Company posts and through hunting, but these sources proved unreliable or insufficient.

By the summer of 1821, the expedition had pushed far beyond its supply lines. Franklin's party found themselves attempting to return to Fort Enterprise, their winter base, across a landscape that offered almost no food. The caribou migrations they'd counted on didn't materialize. Fishing produced meager results. Starvation began to take hold as the group struggled through the barren lands south of the Arctic coast.

When Leather Becomes Food

The descent into desperate hunger happened gradually, then catastrophically. The men first exhausted their remaining pemmican and portable soup. Then they began scraping lichen called tripe de roche from rocks and boiling it into a barely digestible paste that caused severe intestinal distress. Hunting parties ventured out but returned empty-handed more often than not.

Franklin documented the progression toward eating their leather goods in his published narrative of the expedition. The men started by consuming old leather scraps and spare shoes. They discovered that burning the leather to remove the hair, then cutting it into small pieces and boiling it for hours, produced a gelatinous substance that could be swallowed. The soles of boots, being thicker, required longer boiling but yielded more sustenance.

The actual nutritional value of boiled leather is minimal. Leather consists primarily of collagen that breaks down into gelatin when boiled extensively. This provides some protein and perhaps a psychological sense of eating, but nowhere near enough calories to sustain men hauling sledges across frozen terrain. The boot-eating bought time more than it provided real nourishment. Still, when the choice is between eating boots and eating nothing, leather becomes cuisine.

The Darkest Measures

As starvation deepened, the expedition fractured. Franklin sent ahead a group of voyageurs and indigenous guides with whatever strength remained to reach Fort Enterprise and bring back help. This group, led by officer George Back, eventually made it through and organized a rescue. Meanwhile, Franklin's main party struggled on, growing weaker daily.

The rear party, which included voyageur Michel Teroahauté and several others, faced the worst conditions. Evidence suggests that after one member died, some resorted to cannibalism to survive. Michel appeared to have more strength than the others and brought meat he claimed came from hunting, but circumstances suggested a more horrific source. Eventually, Michel shot and killed one of the British officers, and was himself shot by another expedition member who believed Michel had been killing and eating their companions.

Franklin's published account of the expedition carefully obscured the darkest details, but the implication of cannibalism hung over the story. Of the 20 men who set out, only nine survived to return to England. Those who lived did so through boot leather, lichen, scraps of animal hide, and in some cases, measures Franklin chose not to specify in his official narrative.

Legacy of Failure and Fame

The expedition accomplished almost nothing in terms of its geographical objectives. The maps produced were limited and the cost in human life was appalling. By any rational measure, the venture was a disaster that exposed the folly of sending naval officers trained in discipline rather than wilderness survival into one of Earth's harshest environments.

Yet Franklin returned to England as a hero. Victorian society valorized suffering in service of empire and scientific knowledge. The fact that Franklin had endured such extremes and survived made him famous rather than infamous. Publishers rushed his account into print, and readers devoured the tales of hardship. The boot-eating became a symbol of British determination and resilience rather than a warning about poor planning.

This celebration of failure would have deadly consequences. Franklin's fame led to his appointment to command the 1845 expedition to find the Northwest Passage. That voyage ended with the loss of both ships and all 129 crew members in what became the worst disaster in polar exploration history. Franklin's earlier survival had taught him that British willpower could overcome Arctic conditions. The frozen graves scattered across King William Island proved otherwise. In Franklin's case, eating his boots kept him alive just long enough to make an even more fatal mistake.

KEEP ON READING

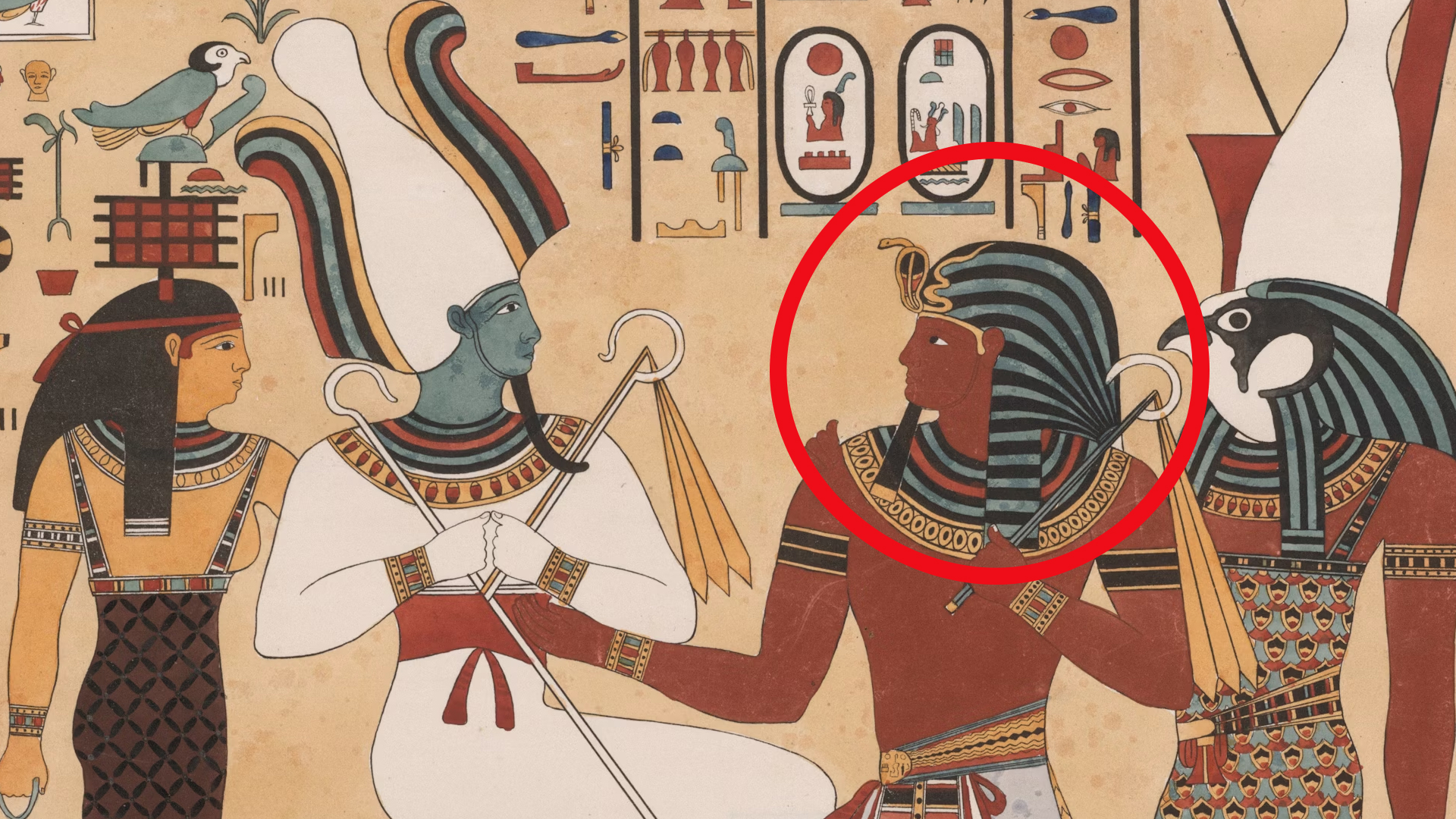

The story of Ching Shih, the Woman Who Became the…

Unknown author on WikimediaFew figures in history are as feared…

By Emilie Richardson-Dupuis Dec 29, 2025

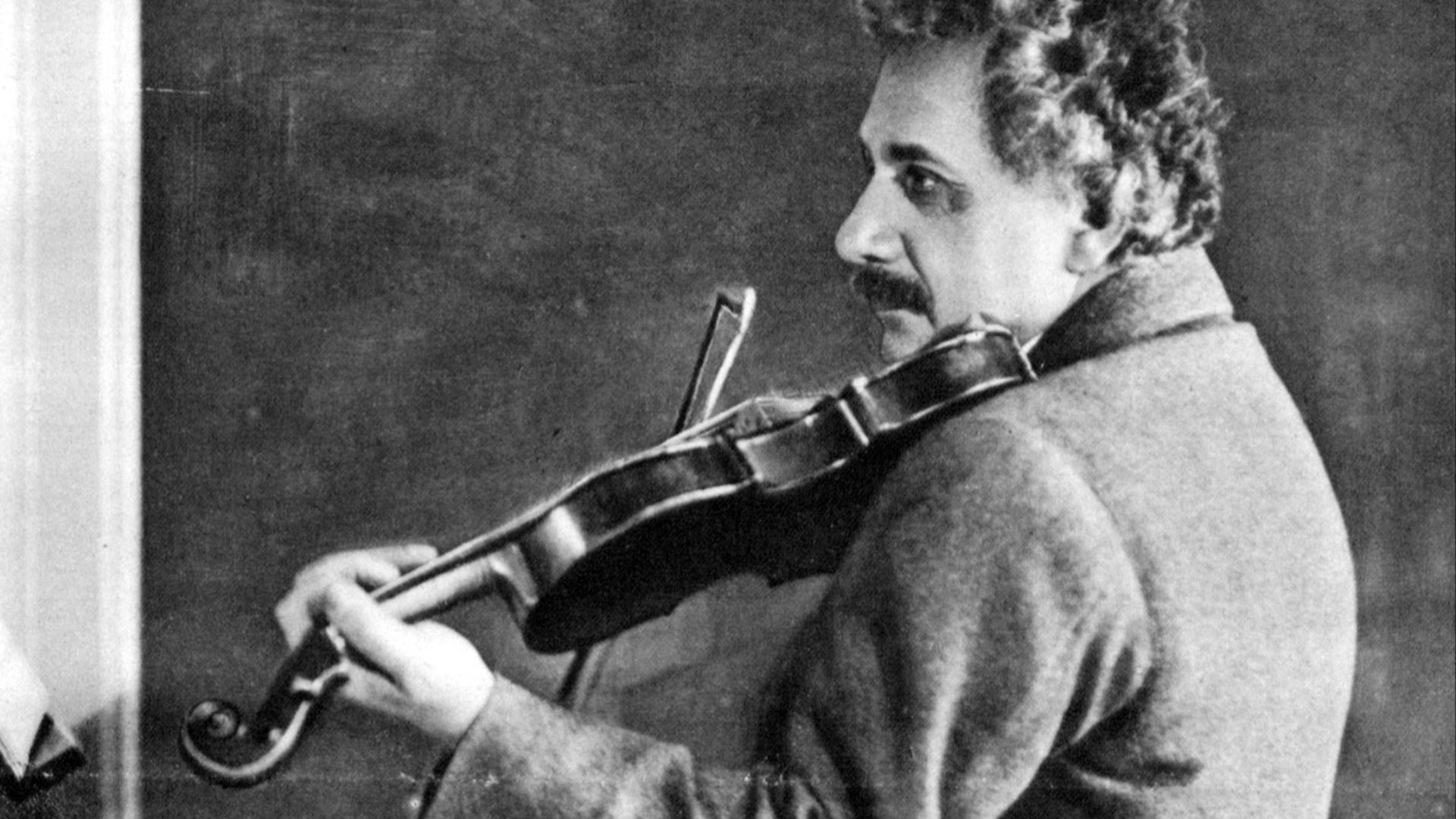

Einstein's Violin Just Sold At An Auction—And It Earned More…

A Visionary's Violin. Wanda von Debschitz-Kunowski on WikimediaWhen you hear…

By Ashley Bast Nov 3, 2025

This Infamous Ancient Greek Burned Down An Ancient Wonder Just…

History remembers kings and conquerors, but sometimes, it also remembers…

By David Davidovic Nov 12, 2025

The Mysterious "Sea People" Who Collapsed Civilization

3,200 years ago, Bronze Age civilization in the Mediterranean suddenly…

By Robbie Woods Mar 18, 2025

Is the golden Age of Humanity Already Behind Us?

Raphael on WikimediaIt’s a very human habit to look back…

By Emilie Richardson-Dupuis Feb 12, 2026

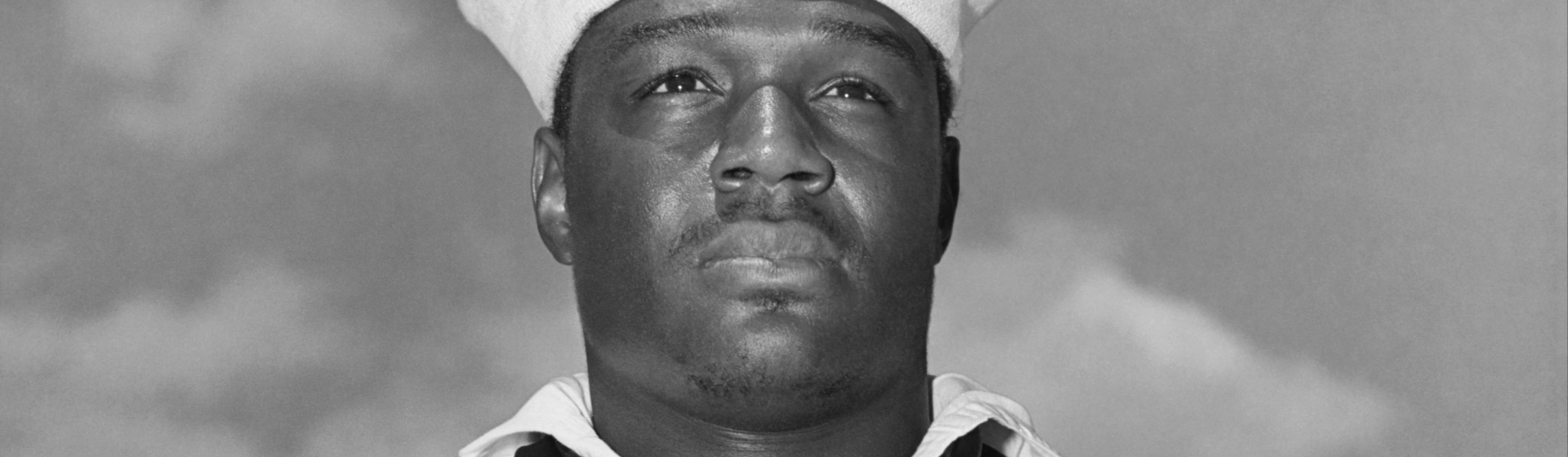

20 Soldiers Who Defied Expectations

Changing the Rules of the Battlefield. You’ve probably heard plenty…

By Annie Byrd Feb 10, 2026