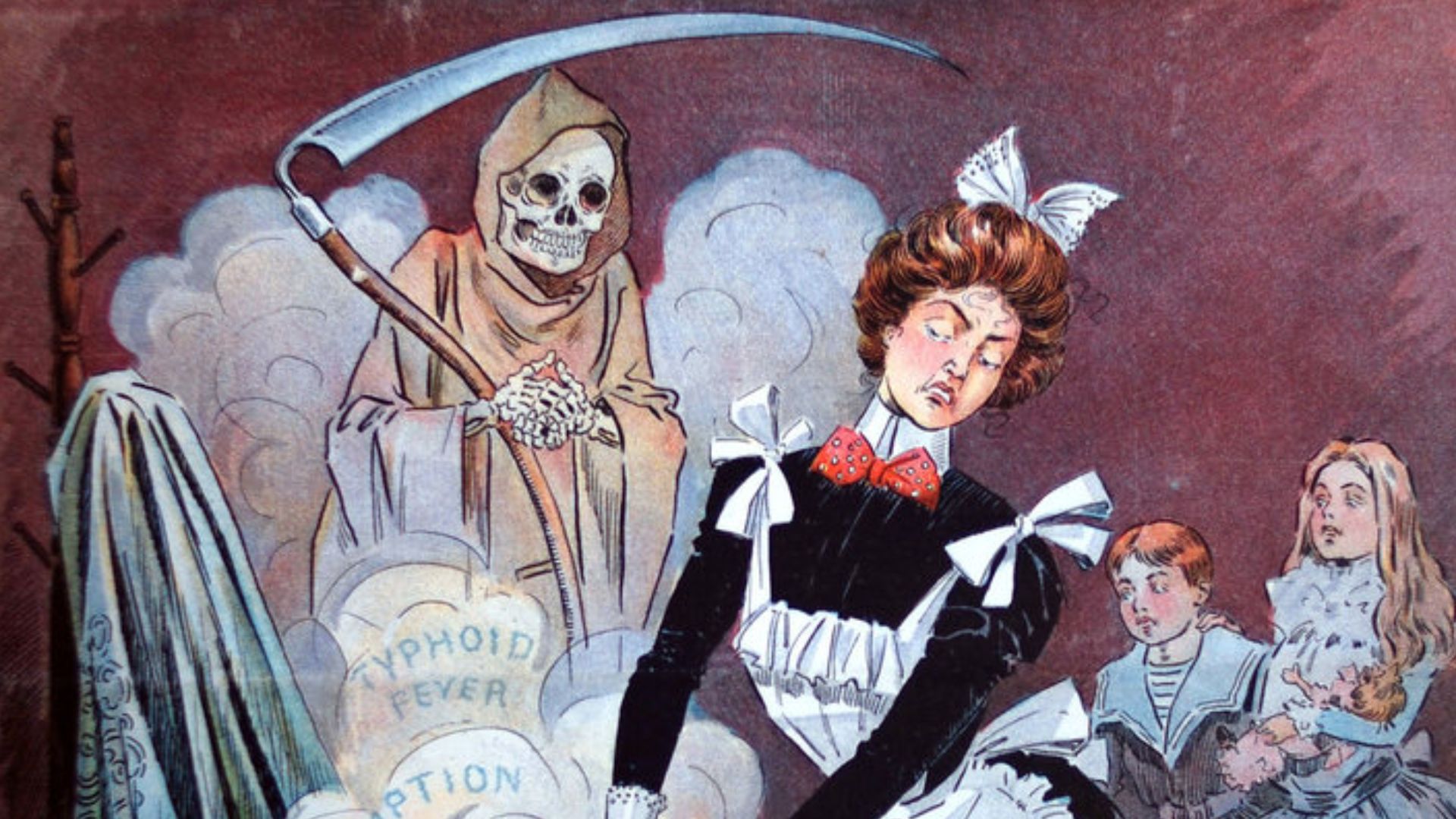

Samuel D. Ehrhart on Wikimedia

Samuel D. Ehrhart on Wikimedia

Most people can picture the Grim Reaper instantly: a robed skeleton, face hidden, scythe angled like a verdict. That image feels ancient because it borrows from older death-figures, but the “full package” you recognize was actually assembled over time rather than handed down intact from one era.

What makes the Reaper stick is how personally the symbol addresses you, even when it’s silent. It doesn’t argue or explain; it simply arrives as a reminder that mortality isn’t theoretical, and it won’t negotiate. After European artists began tying the core features—bones, cloak, and harvesting blade—to death in the late Middle Ages, especially amid plague, the entire figure took on its own identity. Come with us as we explore the history of this ancient being, and just how he wound up as the poster boy for something no one can escape.

Ancient Roots: Death as a Figure You Can Recognize

Long before anyone called it the “Grim Reaper,” Mediterranean cultures experimented with making death legible by giving it a face and a role. In Greek thought, Thanatos functioned as a personification of death, distinct from the broader underworld itself, and artists sometimes rendered him as winged, carrying symbols like an inverted torch that signaled life extinguished. This wasn’t yet the scythe-bearing skeleton, but it set a precedent: death could be embodied, approached, and imagined as an agent rather than an abstraction.

Other figures handled death’s logistics instead of its finality, which mattered for how later cultures pictured “the one who comes for you.” Psychopomps—guides who escort souls—appear across traditions, and in Greek religion, Hermes could serve in that role, conducting the newly dead toward the underworld. When you see later art treat death as a guide or escort, it’s drawing on this older habit of turning transition into a character with a job.

The ferry imagery pushes that idea even further by staging death as a crossing with rules. Charon, described in Greek myth as the ferryman who transports souls across boundary rivers into Hades, embodies the sense that dying involves passage, payment, and separation from the living. Even if the Reaper doesn’t carry an oar, the underlying message survives: you don’t merely stop; you’re taken from one realm to another.

Plague and Pageantry: Medieval Europe Forges the Reaper’s Visual Language

The Reaper’s most recognizable components hardened into place when Europe’s relationship with death became brutally public. Widespread catastrophe, including waves of plague, made mortality a daily spectacle, and artists answered with images that didn’t soften the blow—skeletons, corpses, and personified Death moved from the margins into central scenes. Britannica notes that the Grim Reaper imagery appears in Europe during the Middle Ages, and later accounts emphasize how a skeletal figure and scythe fused into a potent emblem of “reaping” human lives.

In that climate, the Dance of Death (danse macabre) offered a structured, almost ceremonial way to say what the plague screamed: everyone’s equalized. The motif commonly shows Death summoning representatives from every social rank—pope, king, laborer—into a procession toward the grave, a pointed lesson in universality. Reference works tie the concept’s flowering to the late Middle Ages, when memento mori art urged viewers to reckon with life’s fragility.

Specific works and dates underline that this wasn’t a vague mood but an identifiable program of imagery. Scholarship on the Holy Innocents’ Cemetery in Paris discusses an early, influential Dance of Death mural painted in 1424–1425, known today through descriptions and later reproductions. So, when you imagine the Reaper as a communal warning rather than a private nightmare, you’re inheriting that late-medieval impulse to make death visible in shared spaces.

Cloak, Scythe, and Modern Memory: The Reaper Becomes a Global Icon

The scythe is the Reaper’s most aggressive detail, partly because it borrows moral force from ordinary labor. As an agricultural tool, it naturally suggests harvest, and medieval-to-modern symbolism uses that logic to imply lives cut down in sweeping motion, the way grain falls in rows. Even summaries of the figure’s history emphasize that the scythe’s meaning is deliberate: it casts death as a “reaper” who gathers souls the way a farmer gathers crops.

Language helped lock the image into the modern imagination, and the name arrived later than many people assume. The Oxford English Dictionary dates the earliest known use of the noun grim reaper to the 1840s, with early evidence from 1847, which places the label in a world already saturated with earlier death-personifications. In other words, the figure’s visual vocabulary matured first, and the neat English title came afterward.

By the twentieth century, artists could invoke the Reaper with a single silhouette, then bend it toward dread, satire, or philosophy. Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957) famously stages a chess match with the personification of Death, explicitly tying medieval plague atmosphere to modern existential anxiety. The fact that this Death-figure became endlessly referenced and parodied is the clearest proof that the Reaper has outgrown any one theology: you’re not just seeing a monster, you’re seeing a durable cultural instrument for talking about the end.

The Grim Reaper endures because it solves a hard problem: how do you picture something nobody can describe firsthand? By borrowing the logic of harvest, the authority of medieval moral art, and the familiarity of older personifications of death, it turns an invisible boundary into a recognizable figure you can’t easily ignore. You don’t have to believe in a literal skeletal collector to understand the symbol. If the Reaper’s history teaches anything, it’s that cultures keep reinventing death’s face because the subject won’t go away, and neither will our need to give it shape.

KEEP ON READING

The 20 Most Recognized Historical Figures Of All Time

The Biggest Names In History. Although the Earth has been…

By Cathy Liu Oct 4, 2024

10 of the Shortest Wars in History & 10 of…

Wars: Longest and Shortest. Throughout history, wars have varied dramatically…

By Emilie Richardson-Dupuis Oct 7, 2024

10 Fascinating Facts About Ancient Greece You Can Appreciate &…

Once Upon A Time Lived Some Ancient Weirdos.... Greece is…

By Megan Wickens Oct 7, 2024

20 Lesser-Known Facts About Christopher Columbus You Don't Learn In…

In 1492, He Sailed The Ocean Blue. Christopher Columbus is…

By Emilie Richardson-Dupuis Oct 9, 2024

20 Historical Landmarks That Have The Craziest Conspiracy Theories

Unsolved Mysteries Of Ancient Places . When there's not enough evidence…

By Megan Wickens Oct 9, 2024

The 20 Craziest Inventions & Discoveries Made During Ancient Times

Crazy Ancient Inventions . While we're busy making big advancements in…

By Cathy Liu Oct 9, 2024