A Fast, Unsettling Reset of Medieval Life

Even those who aren’t certified history buffs have heard about The Black Death, an unbelievable plague that hit Europe in the mid-1300s. It entered with a speed and severity that still feels shocking to read about today. It changed how people worked, worshipped, governed, and even how they thought about health and danger. Its terrifying impact reshaped an entire continent, and we’re here to walk you through what happened and why it mattered.

Friedrich Hottenroth on Wikimedia

Friedrich Hottenroth on Wikimedia

1. It Didn’t Earn Its Nickname Right Away

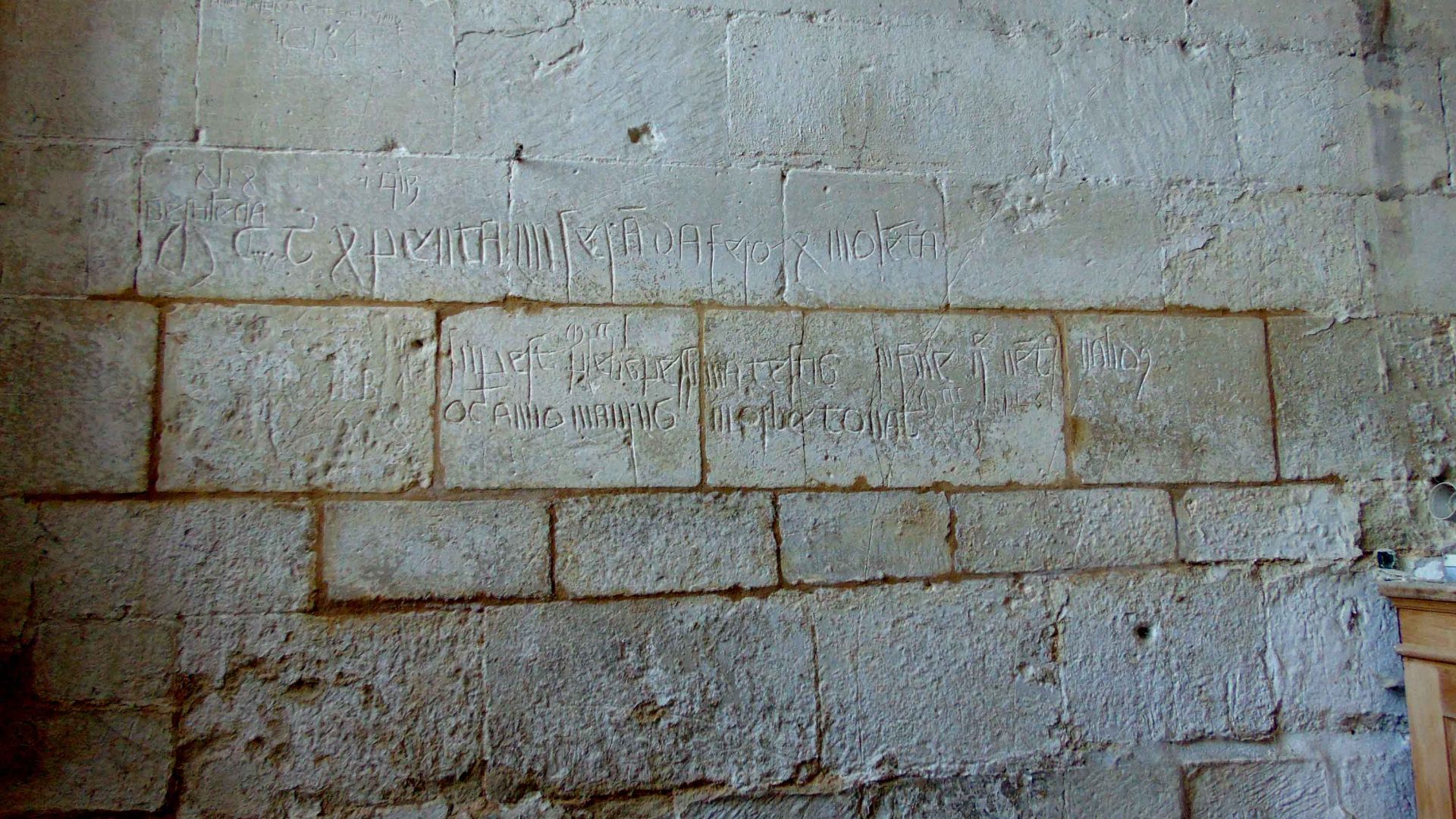

People in the 14th century didn’t usually call it the “Black Death,” since that label became popular later. Contemporary writers more often described it as a “great mortality” or simply “the pestilence.” Should you ever comb through medieval accounts, you’ll notice they focused on the sheer dread and scale rather than a consistent name.

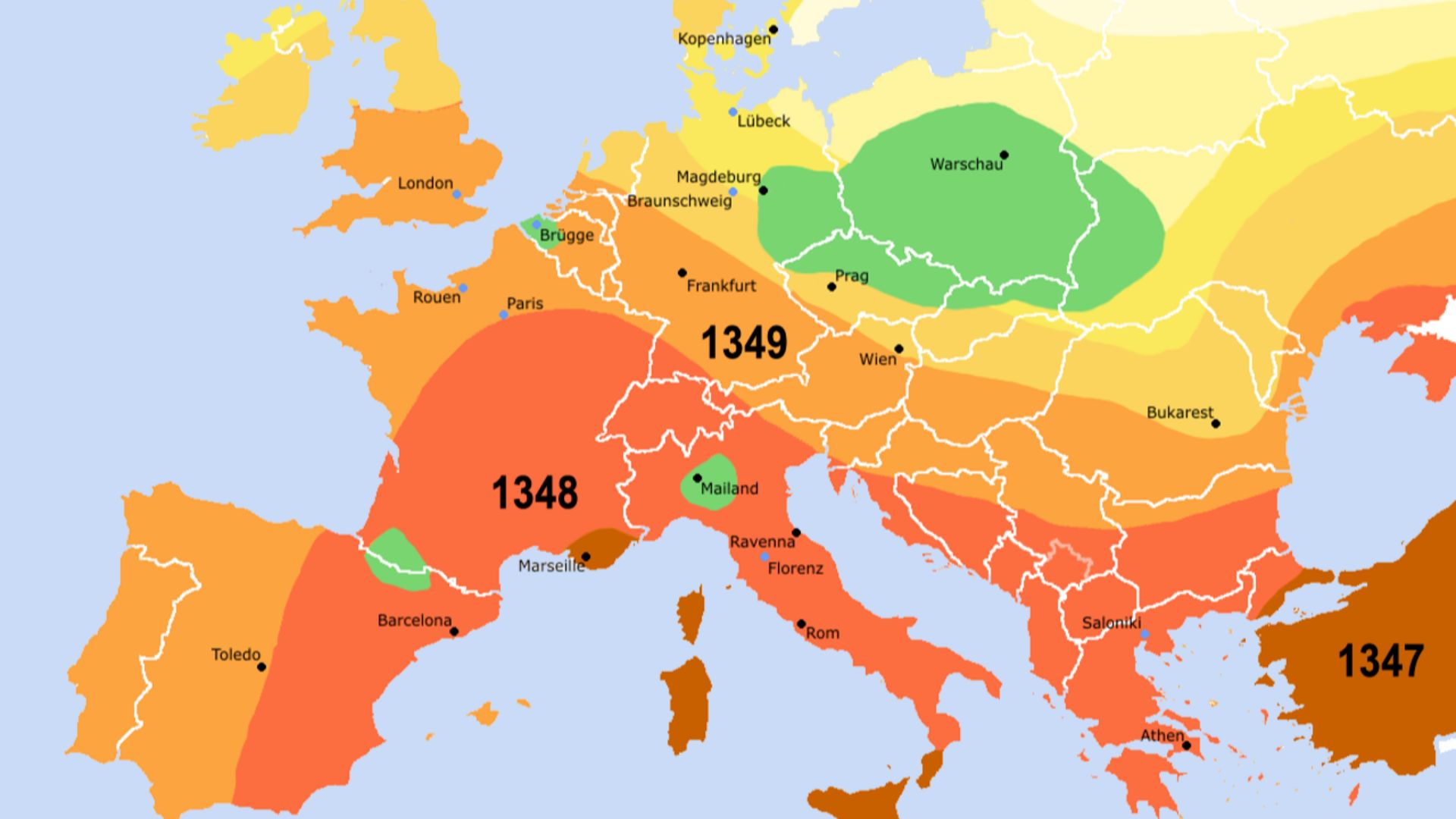

2. It Swept Through Europe

The pandemic’s most infamous European wave is commonly dated from 1347 to 1351. The worst part about it wasn’t that it arrived quickly or surged across regions—it’s that it kept returning in later outbreaks for centuries. Think of those years as the catastrophe’s opening act, not its curtain call.

Original by Roger Zenner (de-WP) Enlarging & readability editing by user Jaybear on Wikimedia

Original by Roger Zenner (de-WP) Enlarging & readability editing by user Jaybear on Wikimedia

3. An Astonishing Number of People Died

Though the exact number is still a little fuzzy, historians estimate that Europe lost roughly 30% to 50% of its population in that first major wave. The reason the exact number varies by region is that records weren’t uniform, and some areas counted poorly. That said, even at the low end, it’s hard to overstate how society buckled under losses that large.

4. Finding the Likely Culprit

A leading explanation links much of the pandemic to Yersinia pestis, a bacterium associated with plague. Evidence from archaeology and historical research supports that it played a major role, though details about transmission routes remain debated.

5. There Was More Than One Form of Plague

The craziest thing about the disease was just how different the symptoms were—which is exactly why it baffled observers. Bubonic plague is famous for swollen lymph nodes, but pneumonic and septicemic forms are also discussed in historical and medical scholarship. Depending on the form and circumstances, the course could be frighteningly fast.

6. Why Cities Were Hit So Hard

We all know that dense populations make it easier for sickness to spread, but the decade’s crowded households and limited sanitation only made it worse. Trade hubs drew constant traffic, and that movement meant fresh opportunities for infection, too.

7. The Role of Trade Routes

The plague moved along routes that merchants and travelers used every day; ships, caravans, and packed inns helped connect outbreaks from one region to the next. You can track its progress on maps and see how commerce unintentionally became a delivery system for disaster.

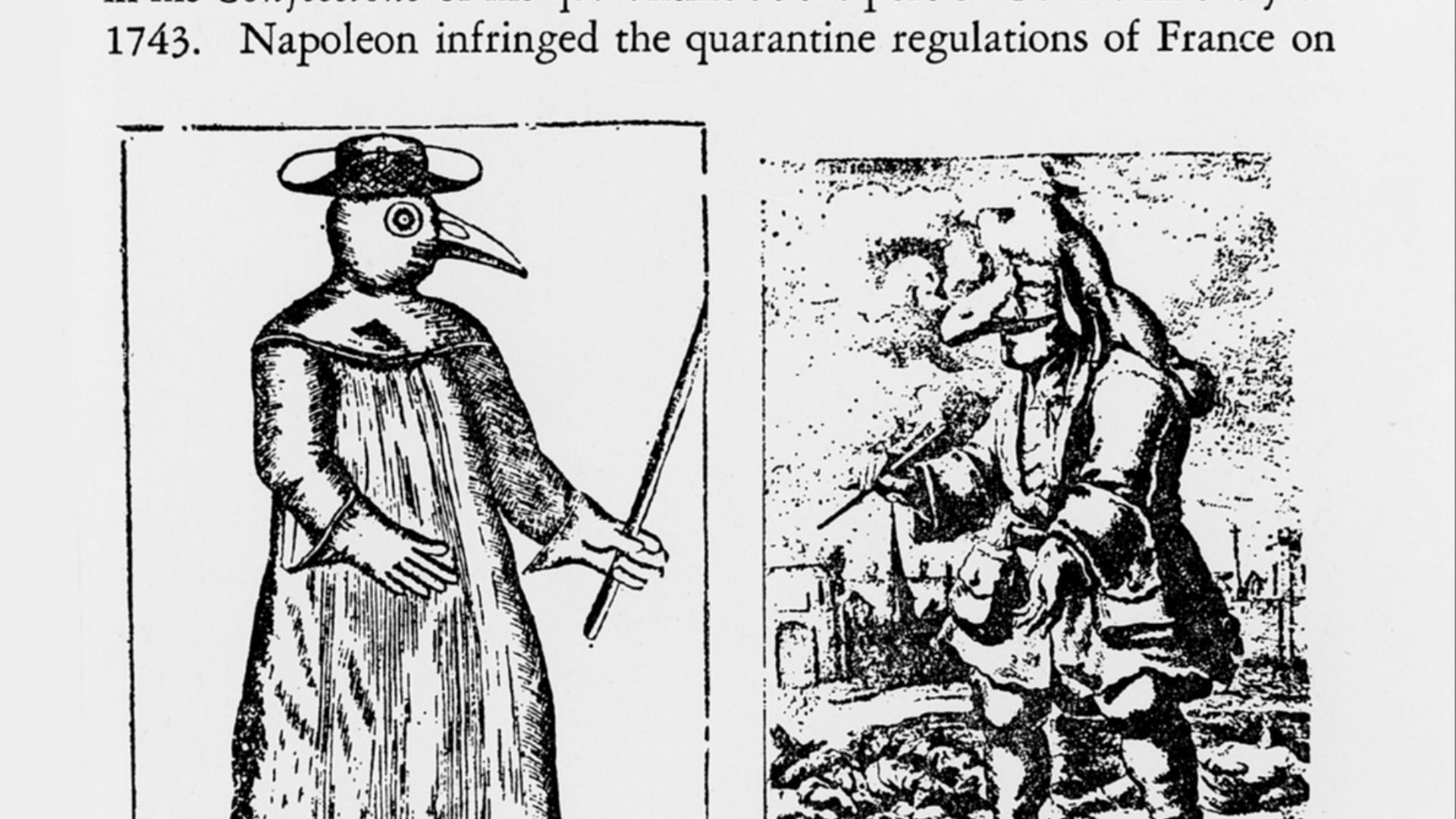

8. Early Quarantine Efforts

Some communities attempted to separate the sick from the healthy, even before the existence of germs was known. Over time, organized quarantine policies emerged, especially in port cities that feared imported disease. While those measures didn’t eliminate plague, they did show that people weren’t passive about the impending threat.

Museums of History New South Wales on Unsplash

Museums of History New South Wales on Unsplash

9. The Meaning of “Forty Days”

The term “quarantine” is often linked to a forty-day waiting period used in certain maritime contexts. But that number didn’t come from a laboratory—it came from administrative reasoning that felt practical at the time.

The Australian National Maritime Museum on Unsplash

The Australian National Maritime Museum on Unsplash

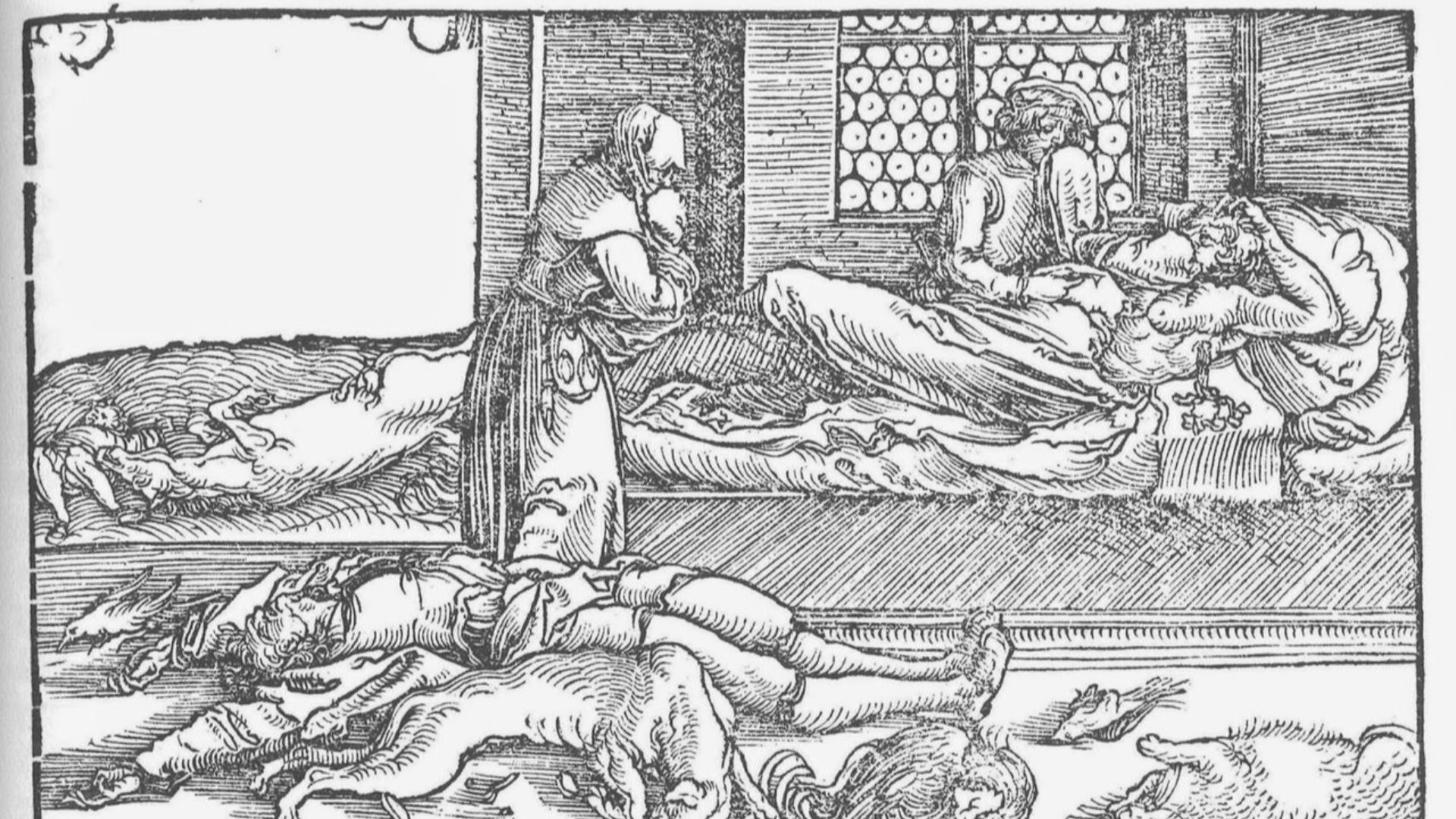

10. The Symptoms People Wrote About

For something that wiped out so many people, it’s no surprise to hear the devastating symptoms. Chroniclers described fever, weakness, and painful swellings that could appear in the groin, armpit, or neck. They also reported rapid decline, sometimes within a few days, which only fueled the panic.

11. Medicine Without Modern Tools

The 1300s didn’t thrive under modern medicine. Medieval strategies leaned on ideas like humors, corrupted air, and imbalances in the body. That meant treatments ranged from herbal remedies to bloodletting, many of which were ineffective or harmful.

Hush Naidoo Jade Photography on Unsplash

Hush Naidoo Jade Photography on Unsplash

12. “Bad Air” and Public Behavior

At the time, many people believed foul smells and “miasma” carried disease, so they tried to avoid stench and breathe “clean” air. Cities sometimes banned certain waste practices or targeted sources of odor as a form of prevention.

Unknown authorUnknown author on Wikimedia

Unknown authorUnknown author on Wikimedia

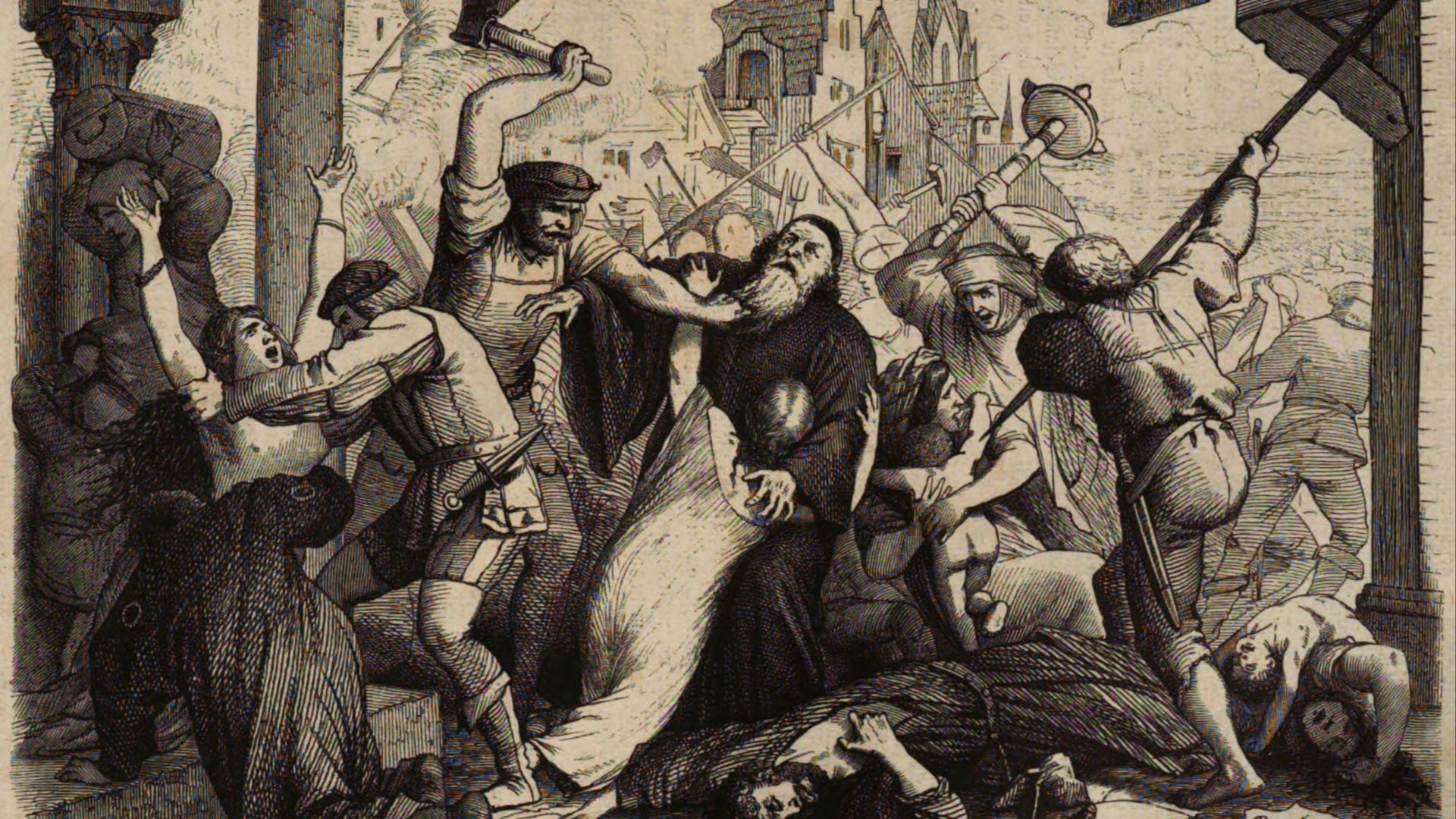

13. It Caused Plenty of Scapegoating and Violence

You can’t really read about the plague without learning a grim lesson in how panic works. During the outbreaks, some communities looked for human villains instead of natural causes. Minorities and outsiders were sometimes accused of poisoning wells or spreading disease on purpose.

14. How Work and Wages Changed

With so many workers dead, labor became scarce in many places. Survivors would sometimes demand higher wages or better terms, which really only upset traditional power structures. Eites weren’t thrilled about workers gaining leverage, which forced governments to try to control pay.

15. The Impact on Farming and Land Use

Fields went untilled in some regions, and marginal farmland was abandoned when communities shrank. Landlords also faced falling rents and fewer tenants, which forced economic adjustments.

16. Religion Under Pressure

People turned to faith for comfort, explanations, and protection, but the scale of death also raised disturbing questions. It wasn’t just the average civilian on their deathbed; clergy died in large numbers, too, and some institutions struggled to replace them. You can sense both devotion and disillusionment in the records, often side by side.

17. Mass Graves and Burial Practices

Normal burial customs couldn’t keep up with the pace, and in some places, bodies were buried quickly in large pits. It sounds unfair, but families and graveyards were overwhelmed, and people didn’t really have a choice.

18. Art and Literature After the Plague

Tragedy often begets art, and after the world reemerged, themes of mortality became more prominent in European culture. Writers and artists referenced death, decay, and spiritual reckoning with a bluntness that matched lived experience.

Pierart dou Tielt (fl. 1340-1360) on Wikimedia

Pierart dou Tielt (fl. 1340-1360) on Wikimedia

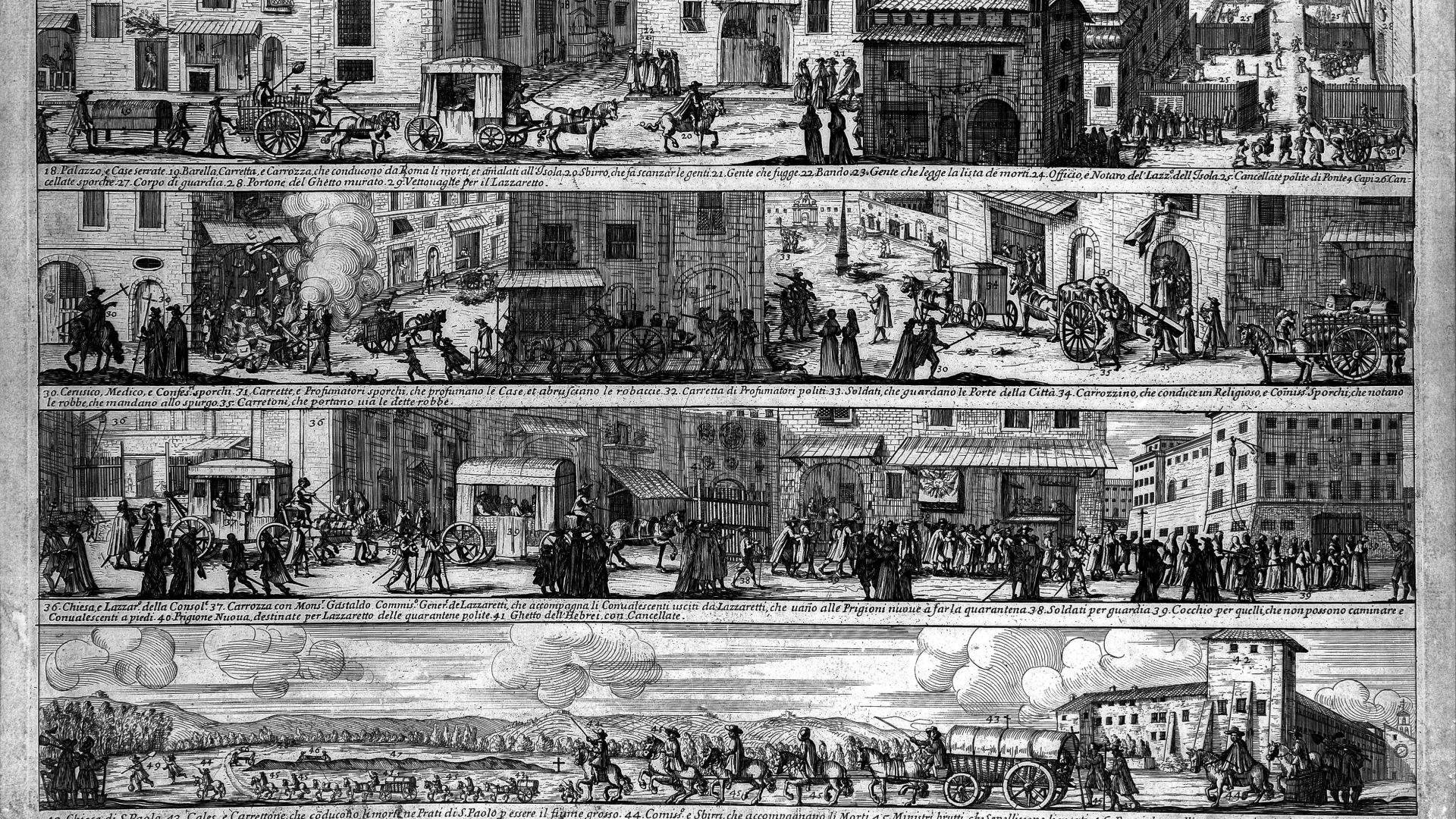

19. Public Health Administration Took Steps Forward

City authorities began experimenting more with regulations around cleanliness, travel, and reporting illness. Officials sometimes tracked cases, restricted gatherings, or managed pesthouses and isolation spaces. Though these tools were crude by modern standards, they helped lay the groundwork for later public health systems.

20. It Didn’t End in 1351

The Black Death’s first wave was the most famous, but plague returned repeatedly in many parts of Europe. Outbreaks flared for centuries, sometimes locally and sometimes widely, keeping fear alive across generations. So, unfortunately, if you’re looking for a tidy ending, history can’t give you one—the plague kept coming back (once in the 1500s, and again in the 1800s).

KEEP ON READING

Ötzi the Iceman’s “Curse”

Mannivu on WikimediaWhen Ötzi the Iceman was discovered in the…

By Emilie Richardson-Dupuis Feb 17, 2026

The Schoolteacher Who Outsmarted the KGB

Dmitry Ratushny on UnsplashShe was a Slovak schoolteacher in her…

By Cameron Dick Feb 17, 2026

The Weird History Of Olympic Medal Designs

DS stories on PexelsOlympic medals look like the simplest part…

By Breanna Schnurr Feb 17, 2026

Appreciating Michael Phelps' Place In Sporting History

Fernando Frazão/Agência Brasil on WikimediaMichael Phelps isn’t just another decorated…

By Rob Shapiro Feb 17, 2026

20 Historical Figures From the 1960s Who Are Still Alive…

The 1960s Aren’t That Far Away, Apparently. The 1960s can…

By Emilie Richardson-Dupuis Feb 17, 2026

20 Facts About The Plague—The Black Death That Wiped Out…

A Fast, Unsettling Reset of Medieval Life. Even those who…

By Annie Byrd Feb 17, 2026