Olympic medals look like the simplest part of the Games: shiny circles, three colors, quick photo, move on. However, history refused to keep things that tidy. The most basic idea of what a medal is has changed more than most people realize.

Behind every podium moment is a design choice that had to survive committees and budgets. Early modern Olympic winners didn’t even get gold, and one set of Games handed out plaques and prizes that looked more like a world’s fair award than sports hardware. Later, the International Olympic Committee tried to standardize the look, which worked until a famously Roman building showed up where Greek imagery was expected. The result is a timeline where tradition and experimentation keep trading places.

When First Place Was Silver

Unknown authorUnknown author on Wikimedia

Unknown authorUnknown author on Wikimedia

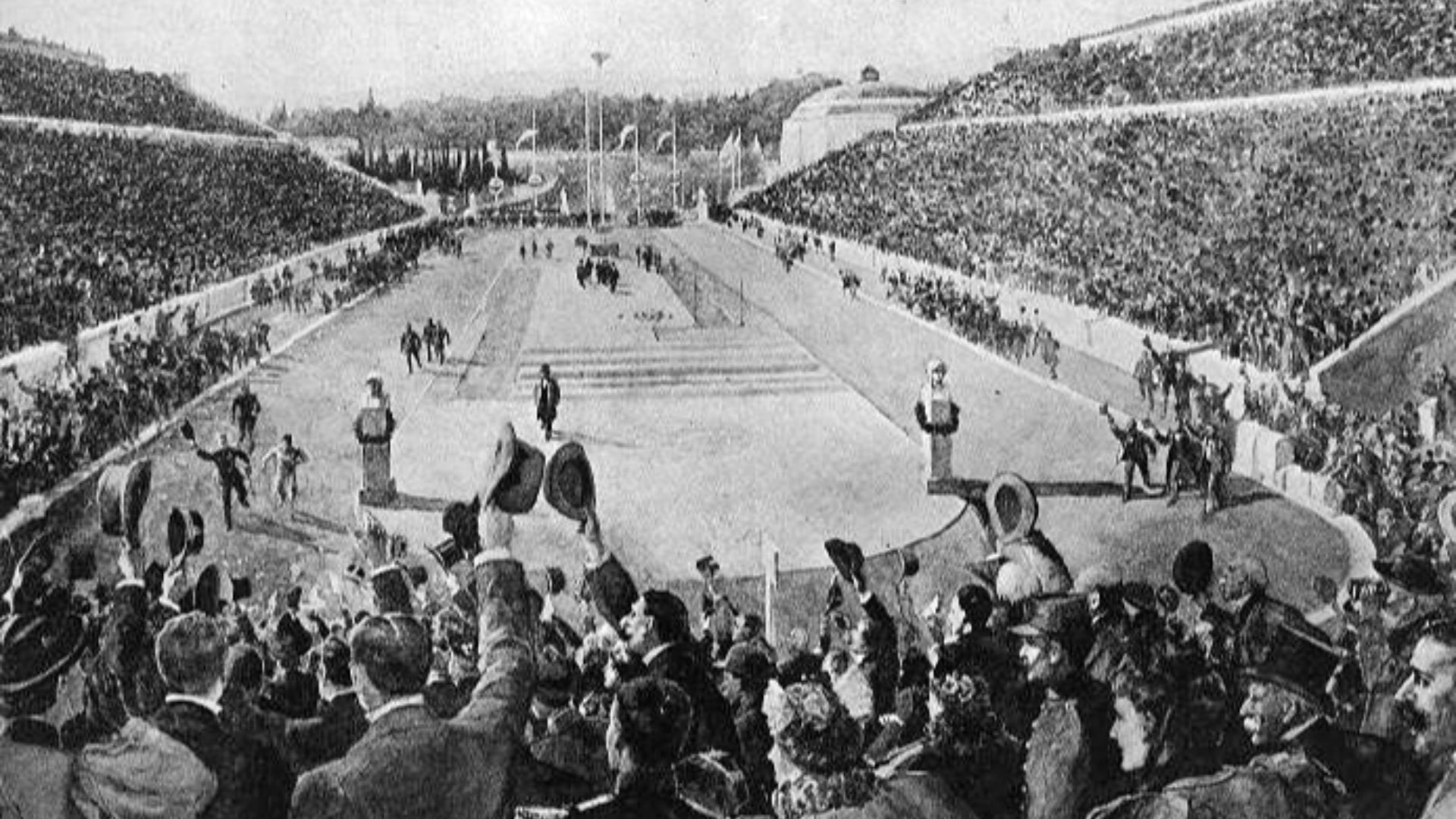

Athens 1896 opened the modern medal era with a twist that surprises anyone raised on gold-silver-bronze podiums. First place received a silver medal, an olive branch, and a diploma, while second place got a bronze or copper medal, a laurel branch, and a diploma. The medal itself leaned hard into mythology, featuring Zeus and winged Victory, in an homage to the Olympics of old.

Paris 1900 took this loose medal system and made it even messier by folding the Games into the Universal Exhibition. The Olympic Museum’s artifact record for a Paris 1900 winner’s plaque describes a piece about six centimeters by 4.2 centimeters, made of silver, and weighing 55 grams, looking more like a piece of Beskar than the classic circular shape we know today. That same record explains that prizes varied by sport, and it quotes the Official Report describing gymnastics awards that ranged from plaques to medals depending on placement.

St. Louis 1904 is where the familiar trio finally arrives as a consistent Olympic practice: gold for first, silver for second, and bronze for third. The Games’ official history calls 1904 the first Olympics, awarding gold, silver, and bronze medals for first through third place. The main difference here was that the medal was fixed to the athlete’s chest with a pin and colored ribbon instead of hanging from the neck.

The Cassioli Template Took Over

Once the Olympics started traveling and growing, consistent medal designs were prioritized. The Olympics’ official medal history for Amsterdam 1928 credits Florentine artist Giuseppe Cassioli with the “traditional” Summer Games obverse, chosen after a competition organized by the IOC in 1921. His Nike, palm, and crown setup came with a built-in blank space for the host city and the Games number.

Olympedia also notes that Olympic medals must be at least 60 millimeters in diameter and three millimeters thick, and that organizing committees design them with IOC approval. We also now know that “gold medal” doesn’t actually mean pure gold. Gold medals today are a mix of 925/1000 silver and a gilding of at least six grams of pure gold. As far as we know, the 1908 and 1912 Olympics were the only two events where winners received solid gold medals.

Cassioli’s Nike became so dominant that it's no surprise it also suffered embarrassing speculation. Reports around Sydney 2000 described a dispute over medals showing a Roman colosseum rather than a Greek temple, and Sydney’s official medal page shows how the host’s identity got pushed to the reverse, with the Opera House, the Olympic torch, and the rings. A separate design clarification says the IOC requested removing the Opera House from the obverse so the Cassioli elements stayed in place.

A Material Switch-Up

Winter Games medals have often acted like the Olympics’ design playground, partly because hosts lean into local craft traditions. Albertville 1992 is a perfect example, with official Olympic medal notes describing medals made “for the first time in glass,” set with gold, silver, and bronze, and entirely hand-made. That same source says Lalique’s production required 35 people and several hundred hours to create 330 medals.

Another design change was made in 2004, again in Athens. The 2004 official medal description says the obverse features the Panathenaic Stadium, and it credits Elena Votsi’s design for combining the eternal flame with the opening lines of Pindar’s Eighth Olympic Ode on the reverse. An IOC news release announcing the new medals even lists production totals: 1,130 gold, 1,130 silver, and 1,150 bronze.

More recently, Sustainability also became part of medal storytelling, primarily with the Tokyo 2020 games. An official Olympics.com post on the Tokyo medal designs says the program collected 78,985 tons of discarded devices, including about 6.21 million used mobile phones, with more than 90 percent of Japan’s local authorities participating. That effort hit collection goals of 30.3 kilograms of gold, 4,100 kilograms of silver, and 2,700 kilograms of bronze by March 31, 2019, turning old tech into the highest honor an athlete can receive.

KEEP ON READING

The story of Ching Shih, the Woman Who Became the…

Unknown author on WikimediaFew figures in history are as feared…

By Emilie Richardson-Dupuis Dec 29, 2025

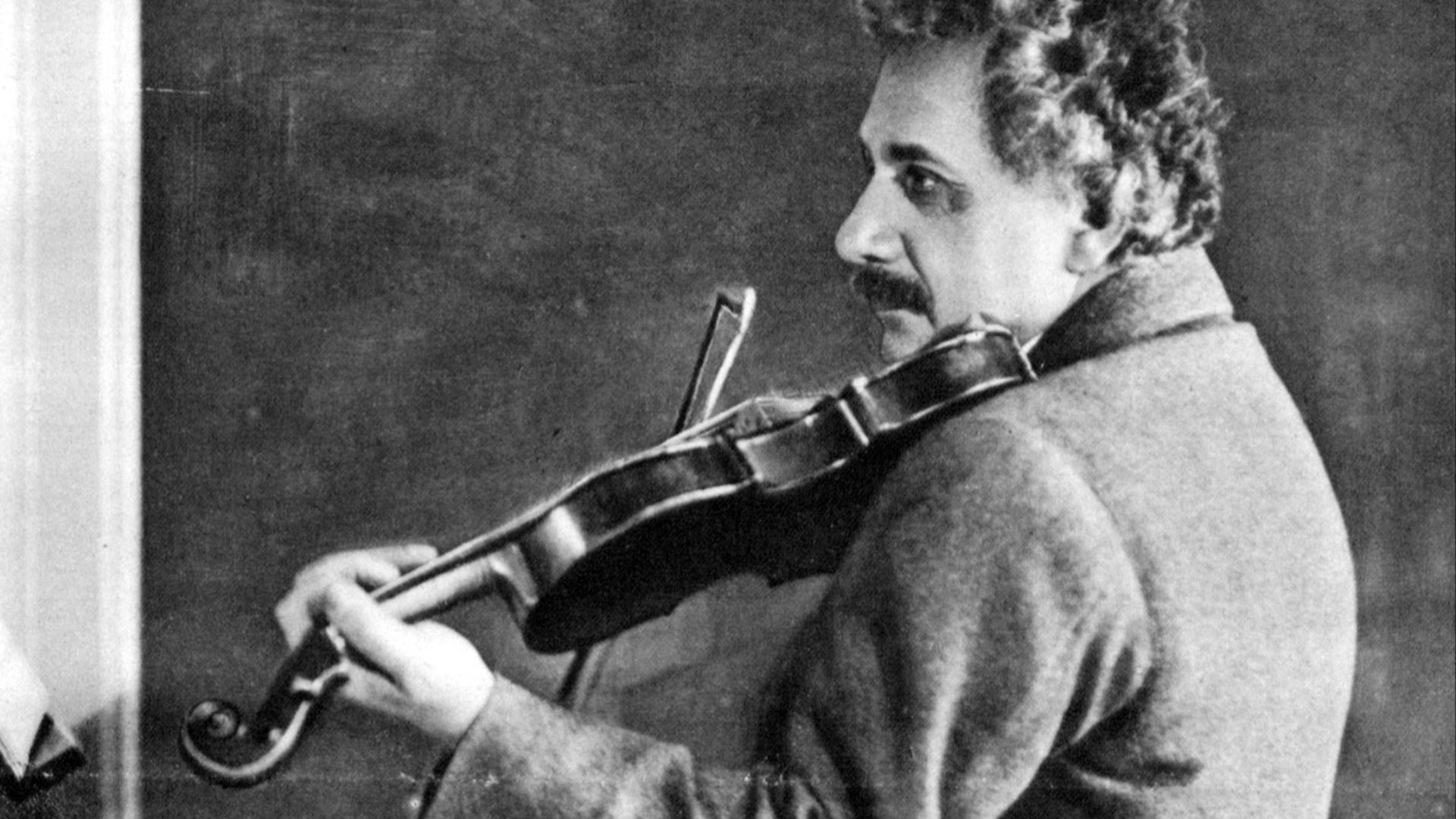

Einstein's Violin Just Sold At An Auction—And It Earned More…

A Visionary's Violin. Wanda von Debschitz-Kunowski on WikimediaWhen you hear…

By Ashley Bast Nov 3, 2025

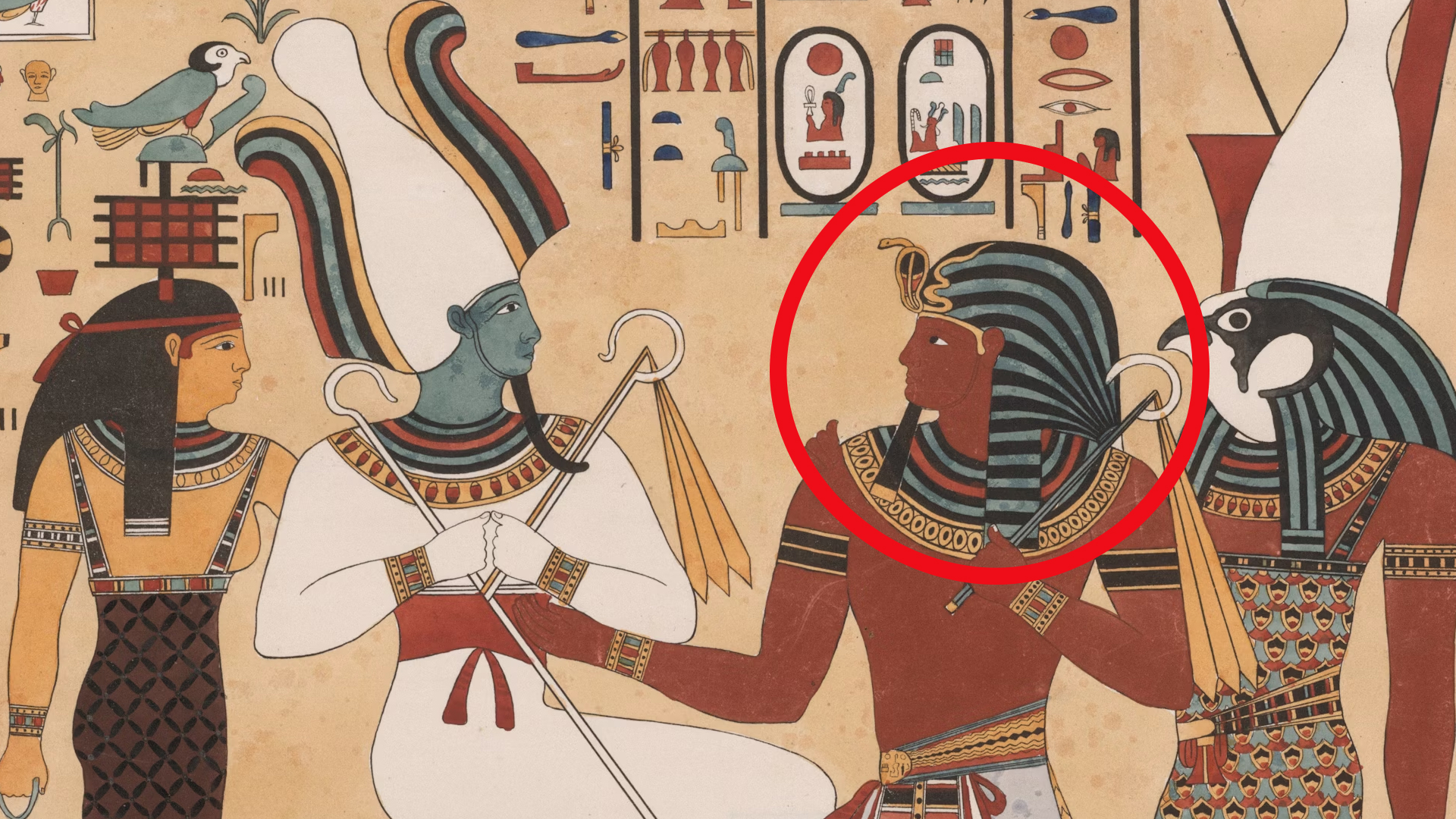

This Infamous Ancient Greek Burned Down An Ancient Wonder Just…

History remembers kings and conquerors, but sometimes, it also remembers…

By David Davidovic Nov 12, 2025

The Mysterious "Sea People" Who Collapsed Civilization

3,200 years ago, Bronze Age civilization in the Mediterranean suddenly…

By Robbie Woods Mar 18, 2025

Ötzi the Iceman’s “Curse”

Mannivu on WikimediaWhen Ötzi the Iceman was discovered in the…

By Emilie Richardson-Dupuis Feb 17, 2026

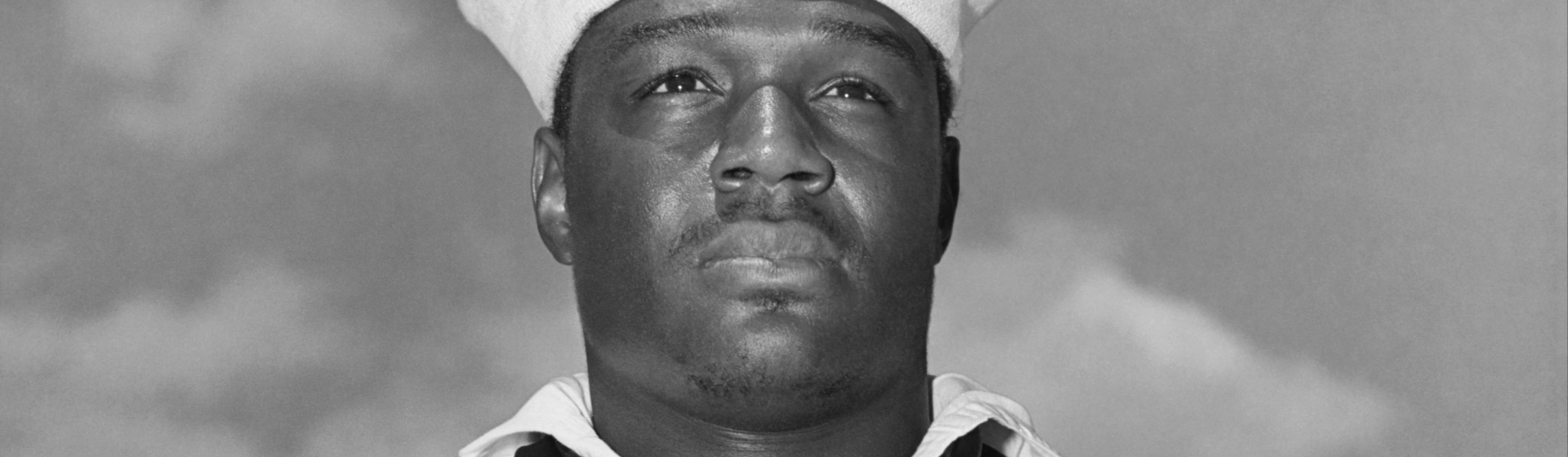

20 Soldiers Who Defied Expectations

Changing the Rules of the Battlefield. You’ve probably heard plenty…

By Annie Byrd Feb 10, 2026