William Notman & Son on Wikimedia

William Notman & Son on Wikimedia

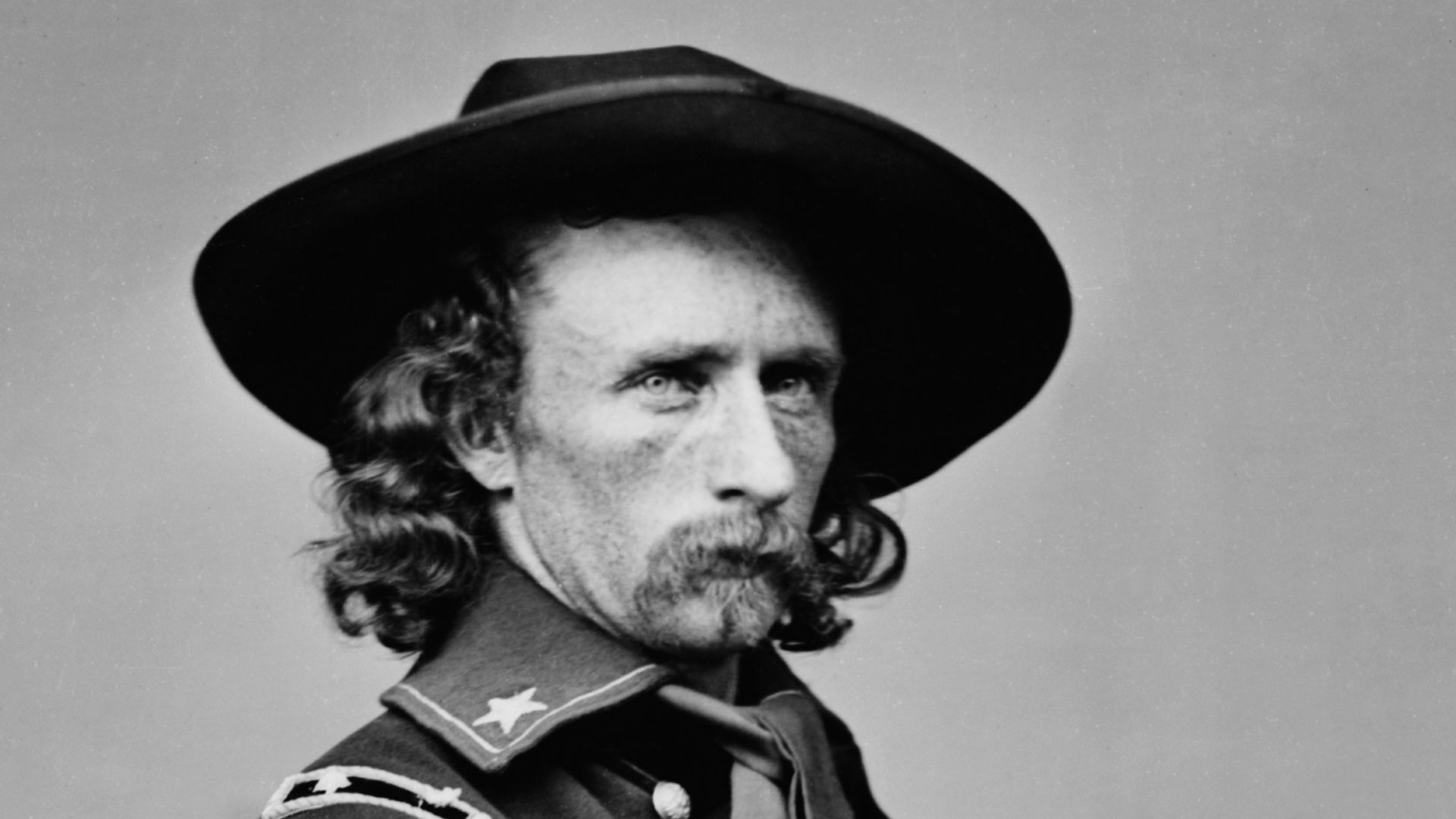

On June 25, 1876, George Armstrong Custer rode into legend—and oblivion. During this military engagement, all 210 soldiers under Custer's immediate command were killed along Montana's Little Bighorn River in what became the most catastrophic defeat the U.S. Army would suffer in the Indian Wars.

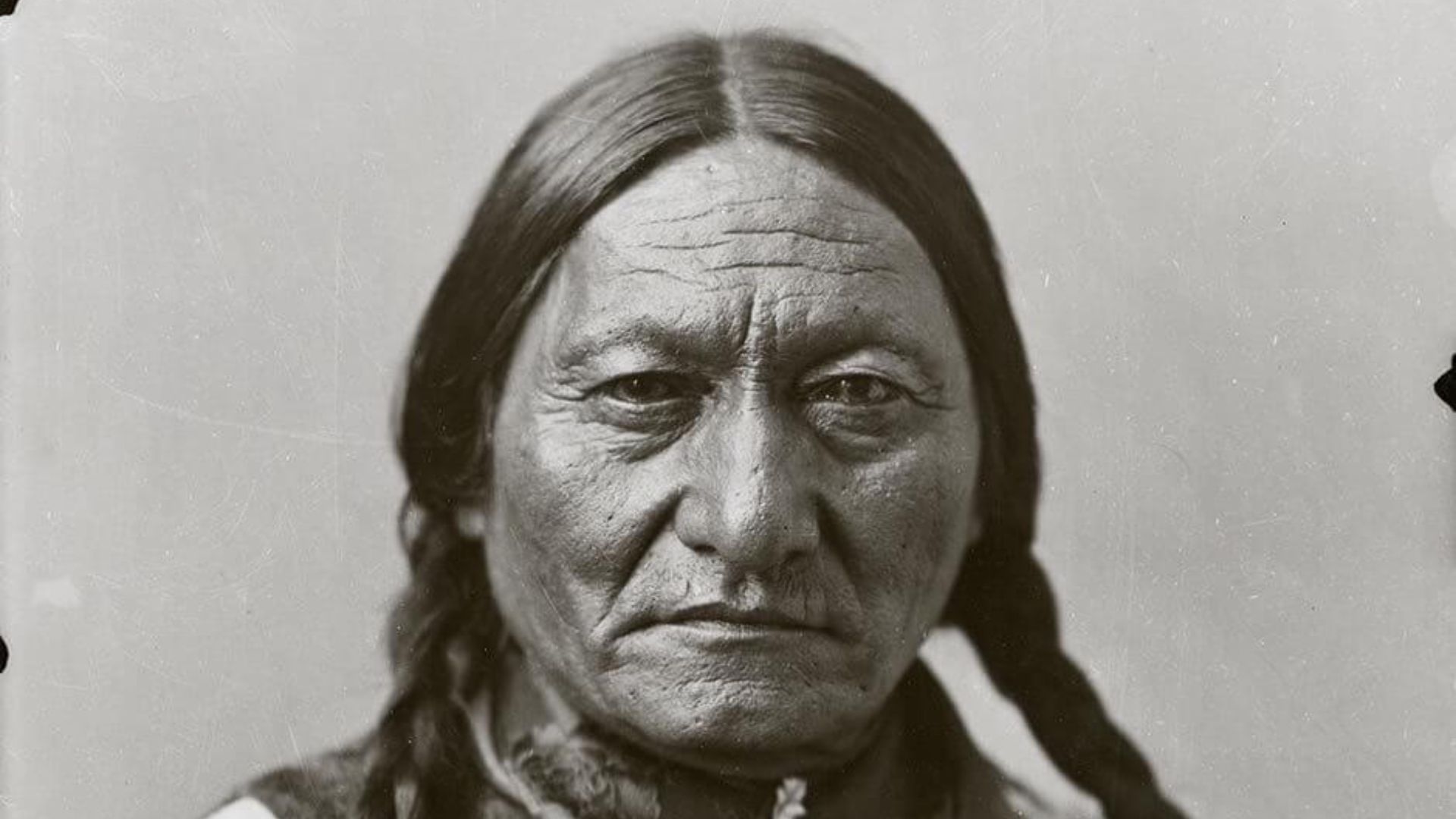

This wasn't some surprise ambush or stroke of bad luck; it was the culmination of years of broken treaties, spiritual preparation, and one man's refusal to bend. Sitting Bull, the Hunkpapa Lakota leader, would go on to become the living embodiment of Native resistance to a government that kept moving the goalposts on them.

The Vision That Foretold Victory

During a Sun Dance on June 6, 1876, Sitting Bull offered one hundred pieces of flesh from his arms as sacrifice and danced until he fainted from blood loss. When he came to, he described soldiers tumbling into their village with their feet pointing skyward—dead men falling from the sky. His people interpreted this as a prophecy of great victory.

This vision came roughly three weeks before Custer showed up, and it electrified the gathered tribes. More than 10,000 Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, as well as some Arapaho had gathered along the river they called Greasy Grass by late spring. They'd left their reservations after the government's insulting ultimatum: return by January 31, 1876, or be considered hostile.

Custer's Fatal Arrogance

Photographer is Mathew Brady (died 1896) and his field staff on Wikimedia

Photographer is Mathew Brady (died 1896) and his field staff on Wikimedia

George Custer was hunting glory, plain and simple. He refused four additional companies of cavalry and two Gatling guns when offered reinforcements. His superiors had given him wide latitude to pursue the enemy, and he took that freedom and created the circumstances of his own undoing.

His plan was a classic hammer-and-anvil attack. Custer intended to hit the village from one side while other forces blocked escape routes. It may very well have worked had Custer not gotten impatient. His scouts found fresh trails on June 23 and 24, and instead of implementing the coordinated strike, he pushed ahead, dividing his already modest force into three battalions.

The Spiritual Leader Who Rallied Thousands

During the period 1868-1876, Sitting Bull developed into one of the most important Native American political leaders. While other chiefs like Red Cloud had moved to reservations and grown dependent on government rations, Sitting Bull maintained his independence, living on the Plains even when it meant isolation. His reputation for "strong medicine" grew precisely because he kept eluding American forces. When threats materialized, warriors from multiple tribes came to his camp seeking his leadership.

The 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie had supposedly guaranteed the Lakota exclusive possession of Dakota territory west of the Missouri River, including the sacred Black Hills. Then gold was discovered in 1874, and suddenly that treaty wasn't worth the paper it was printed on. White miners flooded in, and all Indians were threatened with military action if they didn’t retreat onto their reservations.

The Battle Itself Was Chaos

Unknown authorUnknown author on Wikimedia

Unknown authorUnknown author on Wikimedia

When word spread of the attack, Sitting Bull rallied warriors and saw to the safety of women and children, while Crazy Horse led a large force to meet the attackers. What followed was complete and utter annihilation of Custer's battalion. The Lakota and Cheyenne warriors, fighting to protect their families and way of life, overwhelmed the soldiers through superior numbers and intimate knowledge of the terrain.

Custer's men never had a chance to establish defensive positions. Archaeological evidence suggests Custer attempted to cross the river to threaten fugitive Indian families but encountered resistance and was forced back to what's now called Custer Ridge.

Meanwhile, the other two battalions under Reno and Benteen were pinned down and under siege but managed to hold their positions. They'd live to tell the tale. Custer wouldn't. Neither would any of the 210 men directly under his command.

The Hollow Victory

Victory celebrations were short-lived, as public shock and outrage at Custer's defeat led the government to assign thousands more soldiers to the area. The Army pursued the Lakota and Cheyenne relentlessly, and by deliberately destroying buffalo herds, they eliminated the foundation of Plains Indian life.

In May 1877, Sitting Bull escaped to Canada, while Crazy Horse surrendered at Fort Robinson, Nebraska. The Great Sioux War ended officially on May 7 with the defeat of a remaining Miniconjou band. Sitting Bull would eventually return to the United States in 1881 and spend his final years on the Standing Rock Reservation, his authority as chief no longer recognized by the government.

The Battle of Little Bighorn stands as the greatest Native American military victory against the U.S. Army, but it was also, in a real sense, the beginning of the end of Native resistance. Within a year, Congress had seized the Black Hills and hunting lands that the 1868 treaty had supposedly protected. As for Sitting Bull, he would be shot and killed by Indian police in December 1890, just days before the massacre at Wounded Knee closed the book on armed Native resistance for good.

KEEP ON READING

The Woman Without A Name

Mary Doefour was the woman without a name. In 1978,…

By Robbie Woods Dec 3, 2024

The 10 Worst Generals In History

Bad Generals come in all shapes and sizes. Some commanders…

By Robbie Woods Dec 3, 2024

10 Historical Villains Who Weren't THAT Bad

Sometimes people end up getting a worse reputation than they…

By Robbie Woods Dec 3, 2024

One Tiny Mistake Exposed A $3 Billion Heist

While still in college, Jimmy Zhong discovered a loophole that…

By Robbie Woods Dec 3, 2024

The Double Life And Disturbing Death of Bob Crane

Bob Crane was the star of Hogan's Heroes from 1965-1971.…

By Robbie Woods Dec 3, 2024

The Most Surprising Facts About North Korea

North Korea may be the most secretive state in the…

By Robbie Woods Dec 3, 2024