A Mammoth Language

The history of Chinese is easiest to follow if you keep two tracks in mind at the same time: the spoken language (which has changed dramatically across regions and centuries) and the writing system (which has been remarkably continuous, even as scripts, standards, and reforms evolved). Because written Chinese often preserved older styles long after speech had moved on, you’ll see moments where “Chinese” looks one way on the page while it’s shifting quickly in how people speak it. If you're ready to dive deeper into the history of the language, here are 20 fascinating facts that might just leave you in awe.

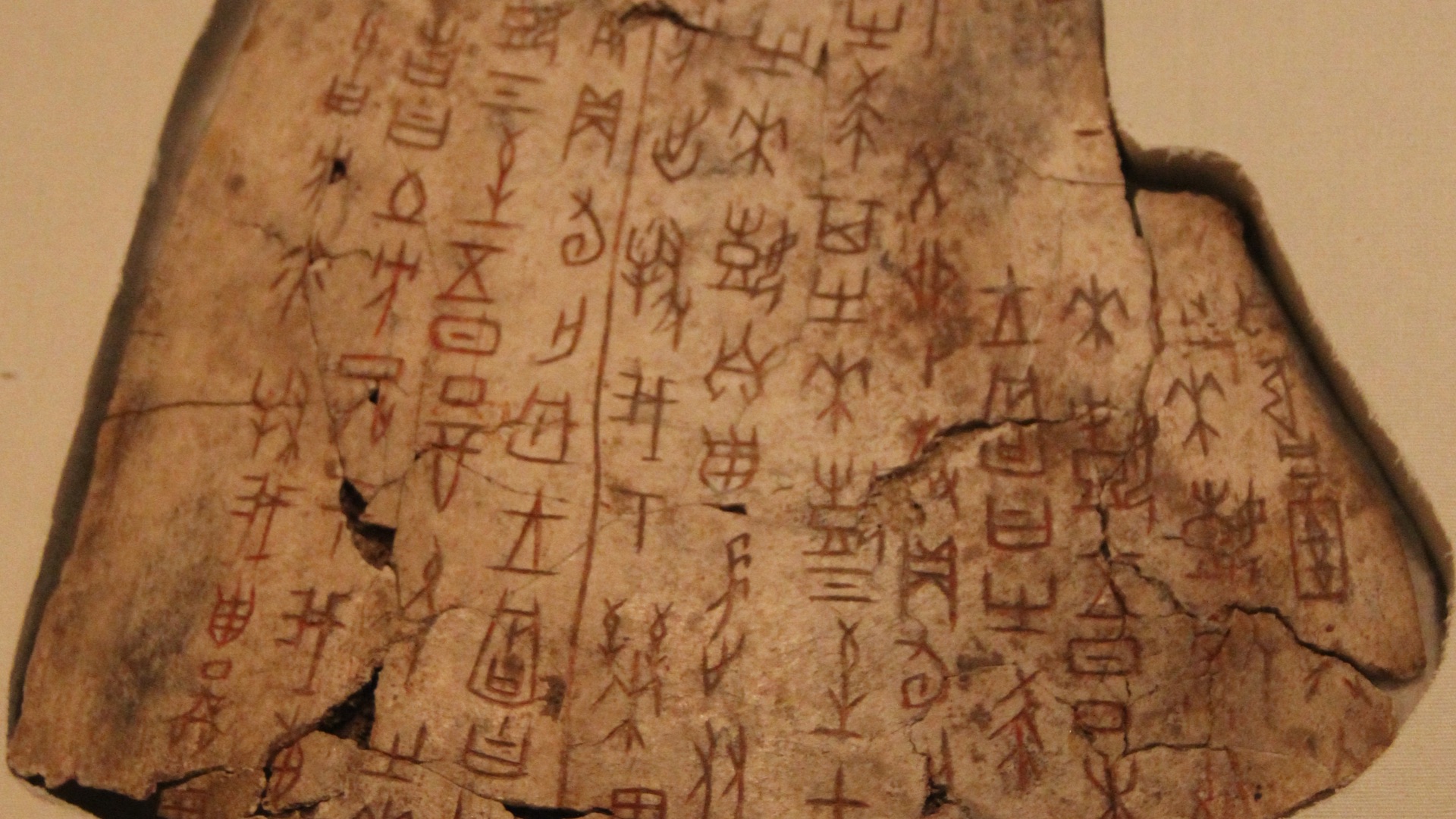

1. Oracle-Bone Inscriptions Anchor the Earliest Big Written Record

Oracle-bone inscriptions are widely treated as the oldest attested form of written Chinese, tied to the late Shang period. They were carved mainly for divination and record the outcomes of official rituals, which makes them unusually valuable for dating early written usage. Even if you never study the script in depth, it’s hard to overstate how central this corpus is for understanding early Chinese writing.

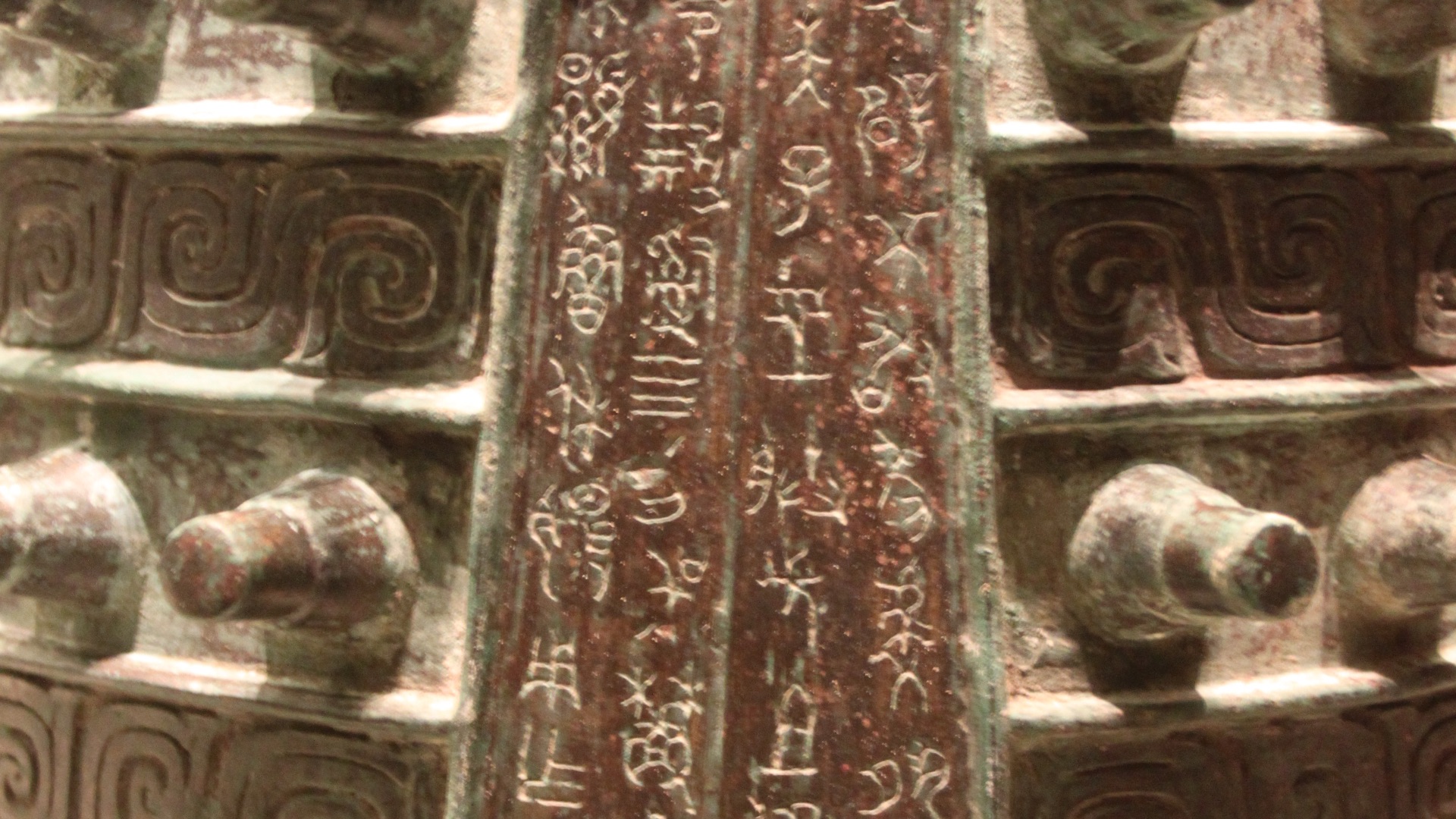

2. Bronze Inscriptions Show Writing Moving Into Public Memory

Inscribed ritual bronzes from the late Shang and Western Zhou dynasties preserve a second major early stream of Chinese writing. These texts often include clan names, commemorations, awards, ceremonies, or accounts of events, which helps you see how writing functioned beyond divination. Because many inscriptions were cast into vessels, they also document how durable writing could be in elite contexts.

3. The Qin Government Standardized Character Forms for Administration

During the Qin dynasty, the state pursued a major standardization of written forms to reduce regional variation that complicated governance. Many summaries connect this standardization with Qin policies under Qin Shi Huang and with the promotion of standardized seal script across the empire. When you track later script history, this moment keeps coming up because it sets a precedent for state-backed language planning.

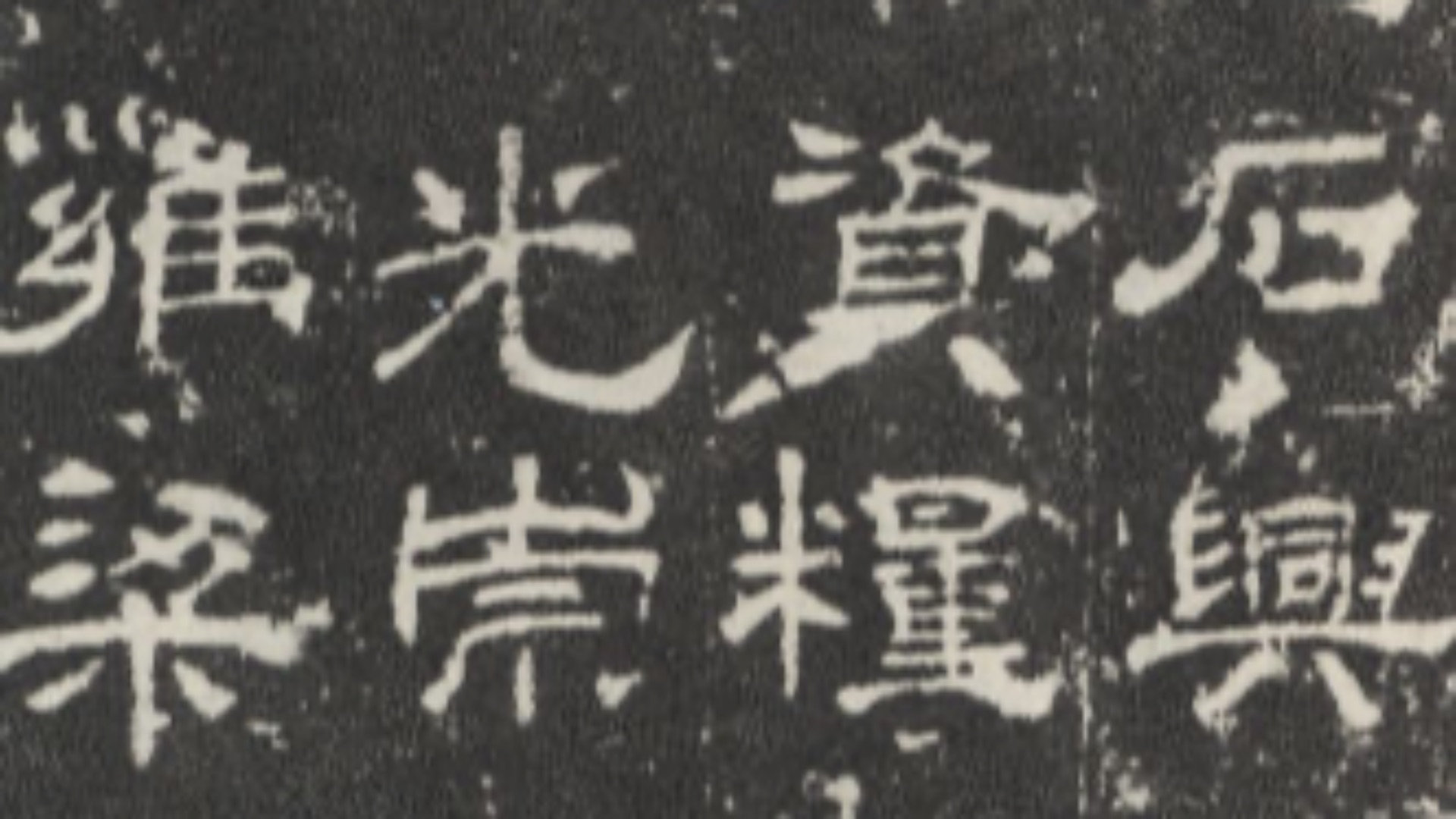

4. Clerical Script Became the Workhorse Style for Records and Documents

Clerical script (lishu) evolved into a practical, brush-friendly style that suited routine paperwork much better than earlier forms. It emerged during the Warring States period and became dominant in the Han dynasty, showing up in both official records and more personal writing contexts. If you’re wondering why later scripts could look so different from seal styles, lishu is one of the key turning points.

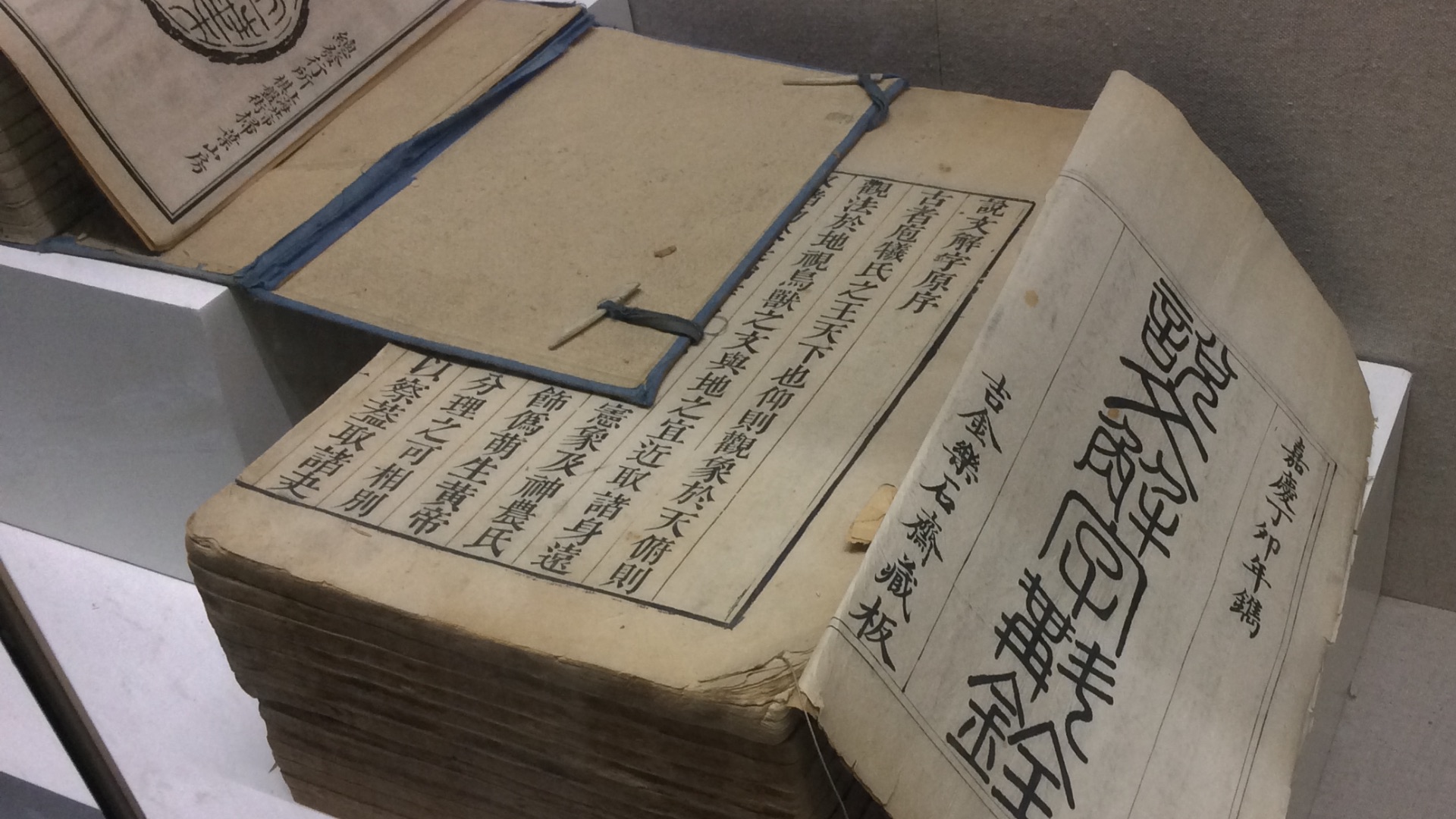

5. Shuowen Jiezi Turned Characters Into a Subject You Could Systematize

The Shuowen Jiezi is a landmark dictionary compiled by Chinese calligrapher Xu Shen around 100 CE during the Eastern Han dynasty. It’s especially known for offering a comprehensive analysis of character structure and for organizing entries under shared components called radicals. That approach shaped how later scholars thought about characters, even when they disagreed with Xu Shen’s explanations.

6. Paper Made Written Chinese Easier to Copy, Store, and Teach

Cai Lun is traditionally credited with developing or improving papermaking around 105 CE, which helped paper become a practical writing surface. Once paper spread, copying and archiving texts became cheaper and more accessible than relying on bamboo slips or silk, which were the principal options at the time.

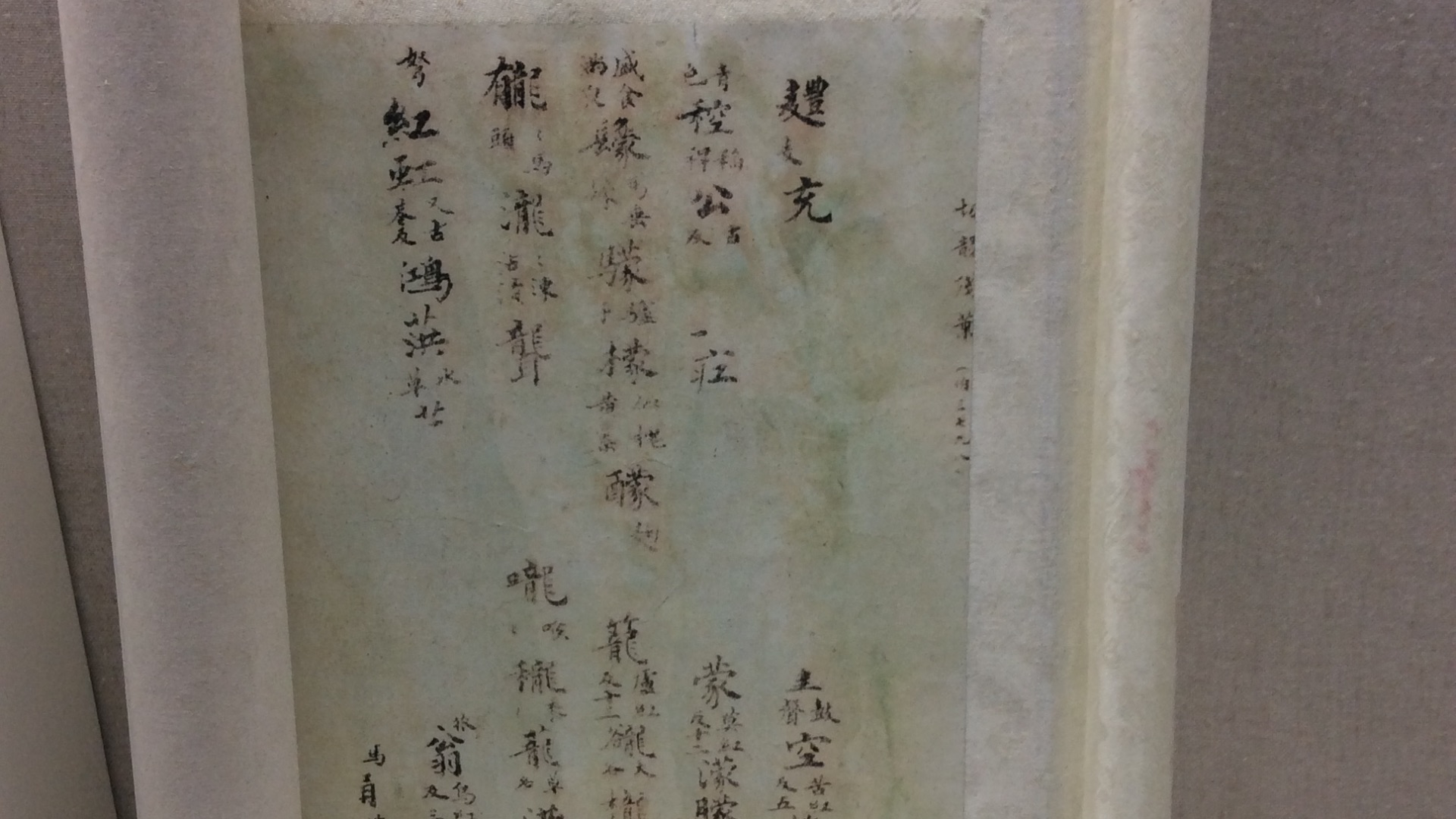

7. Qieyun Offered a “Correct Reading” Reference Across Dialects

Published in 601, the Qieyun was designed as a guide to reading classical texts and it used the fanqie method to indicate pronunciation. It became an essential documentary source for reconstructing Middle Chinese because it preserves categories that later changed in different spoken varieties. Even today, discussions of historical Chinese sound systems often circle back to this book and its revisions.

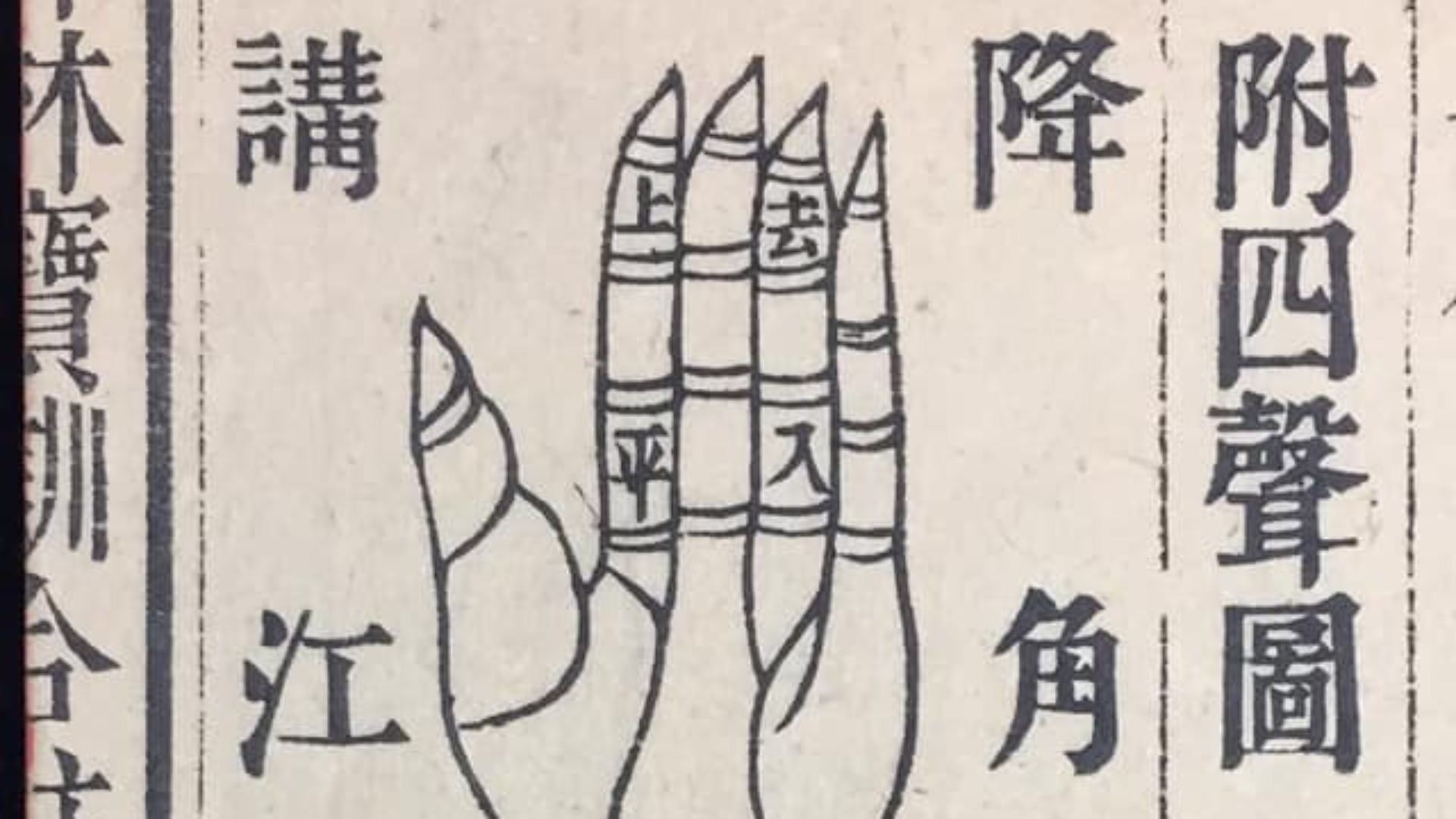

8. The Four Traditional Tone Classes Became a Long-Lasting Analytical Tool

Middle Chinese is commonly described using four traditional tone classes: level, rising, departing, and entering. These categories mattered for poetry and later became a standard framework for comparing how tones split, merged, or disappeared in modern varieties. If you’ve heard that Mandarin lost the “entering” tone while other varieties preserved it differently, this is the historical reference point people mean.

Thích Tịnh Thiện 釋淨善 on Wikimedia

Thích Tịnh Thiện 釋淨善 on Wikimedia

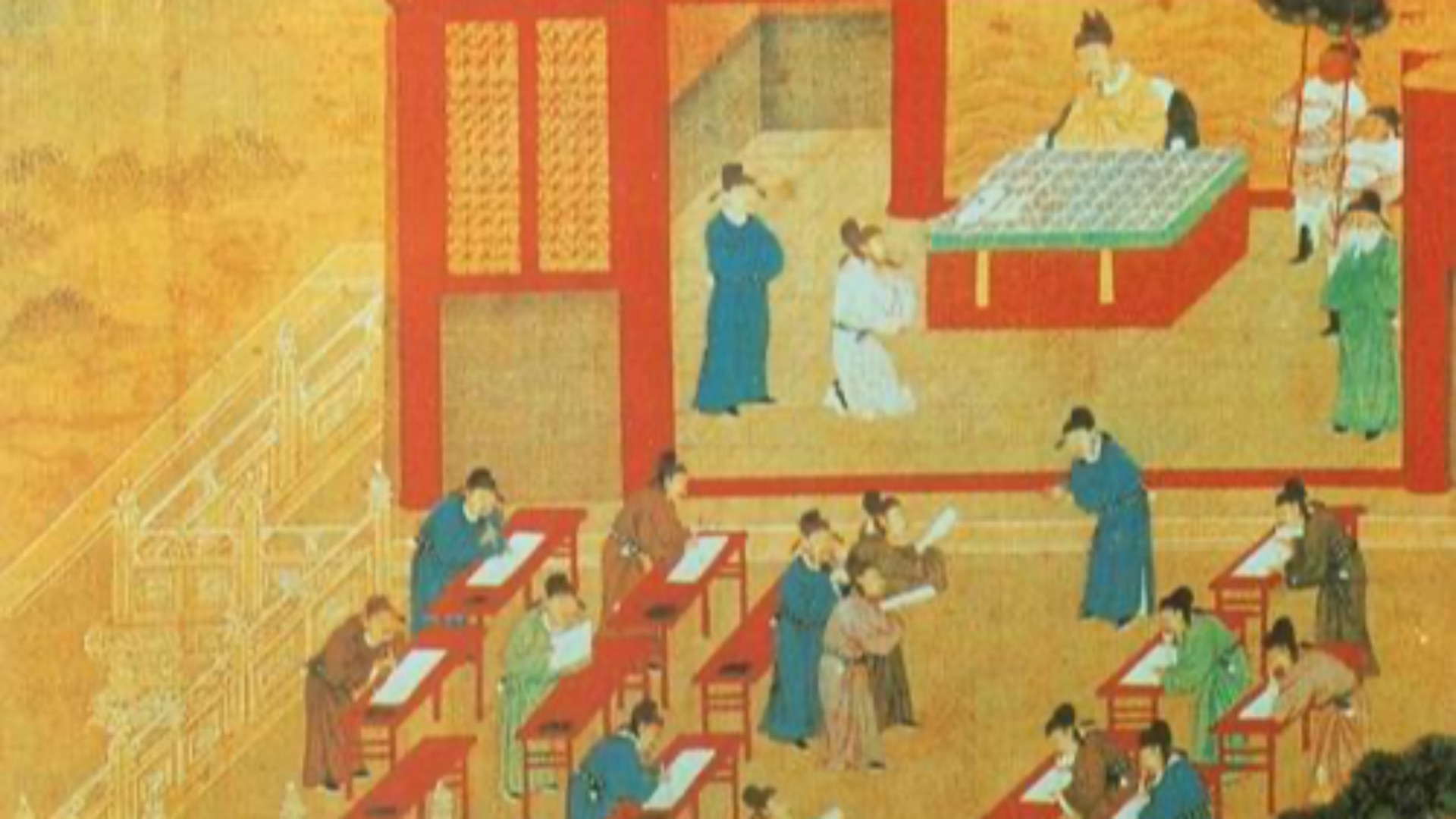

9. The Exam System Reinforced Shared Literary Norms Over Centuries

The imperial examination system used written testing as a major recruitment channel and lasted until its abolition in 1905. Because success depended on mastery of classical texts and elite writing practices, the exams strongly reinforced what educated written Chinese was supposed to look like. This pressure helped stabilize prestigious written norms even while everyday speech remained regionally diverse.

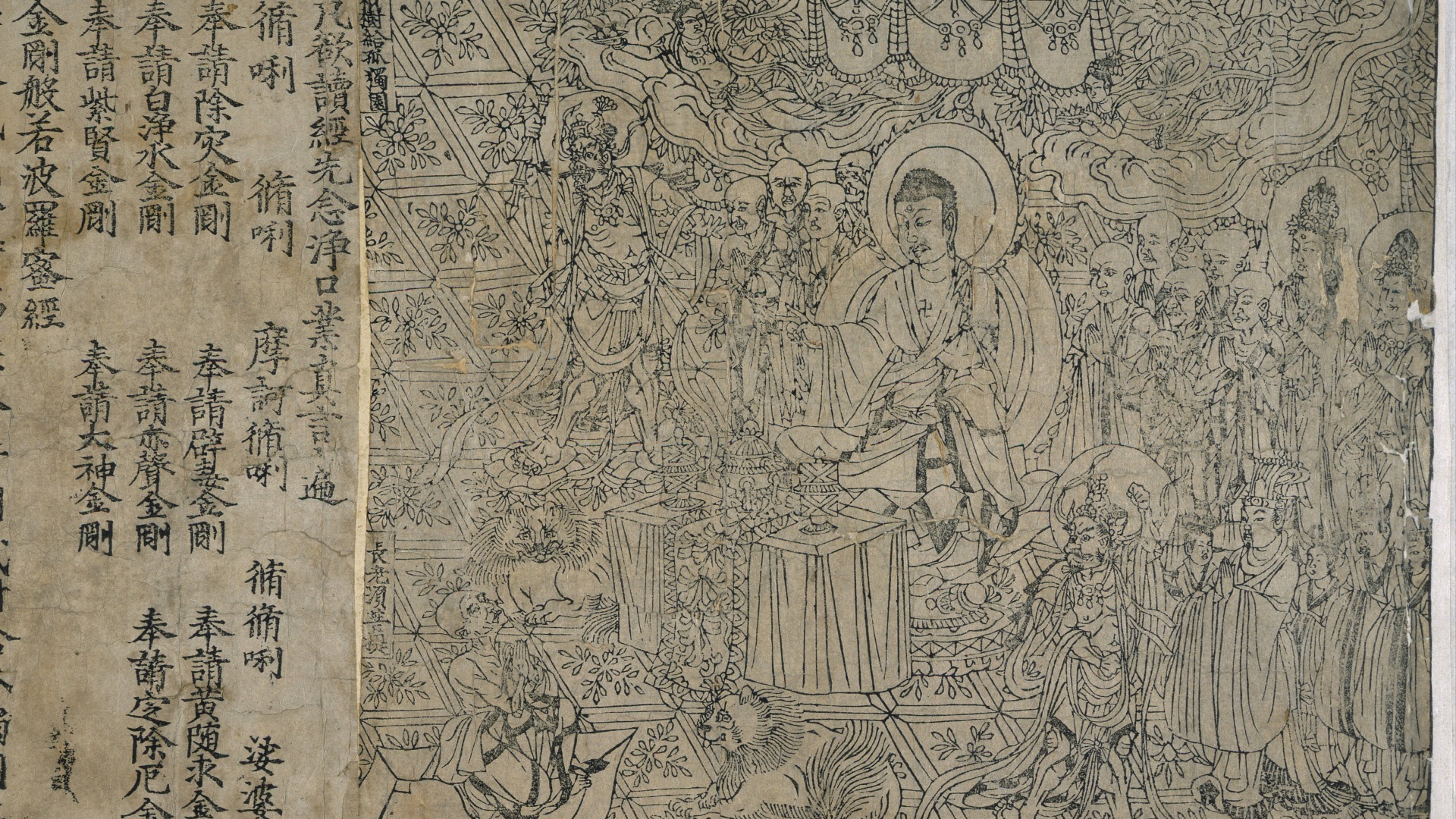

10. Printing Accelerated Text Circulation and Standardized “Authoritative” Editions

Printing technologies enabled much broader dissemination of texts, which changed how quickly written Chinese could spread across regions. A famous milestone is the Diamond Sutra, dated 868, often cited as the earliest surviving dated complete printed book. Once large-scale printing took hold, it became easier to fix canonical versions of texts and teach from more uniform materials.

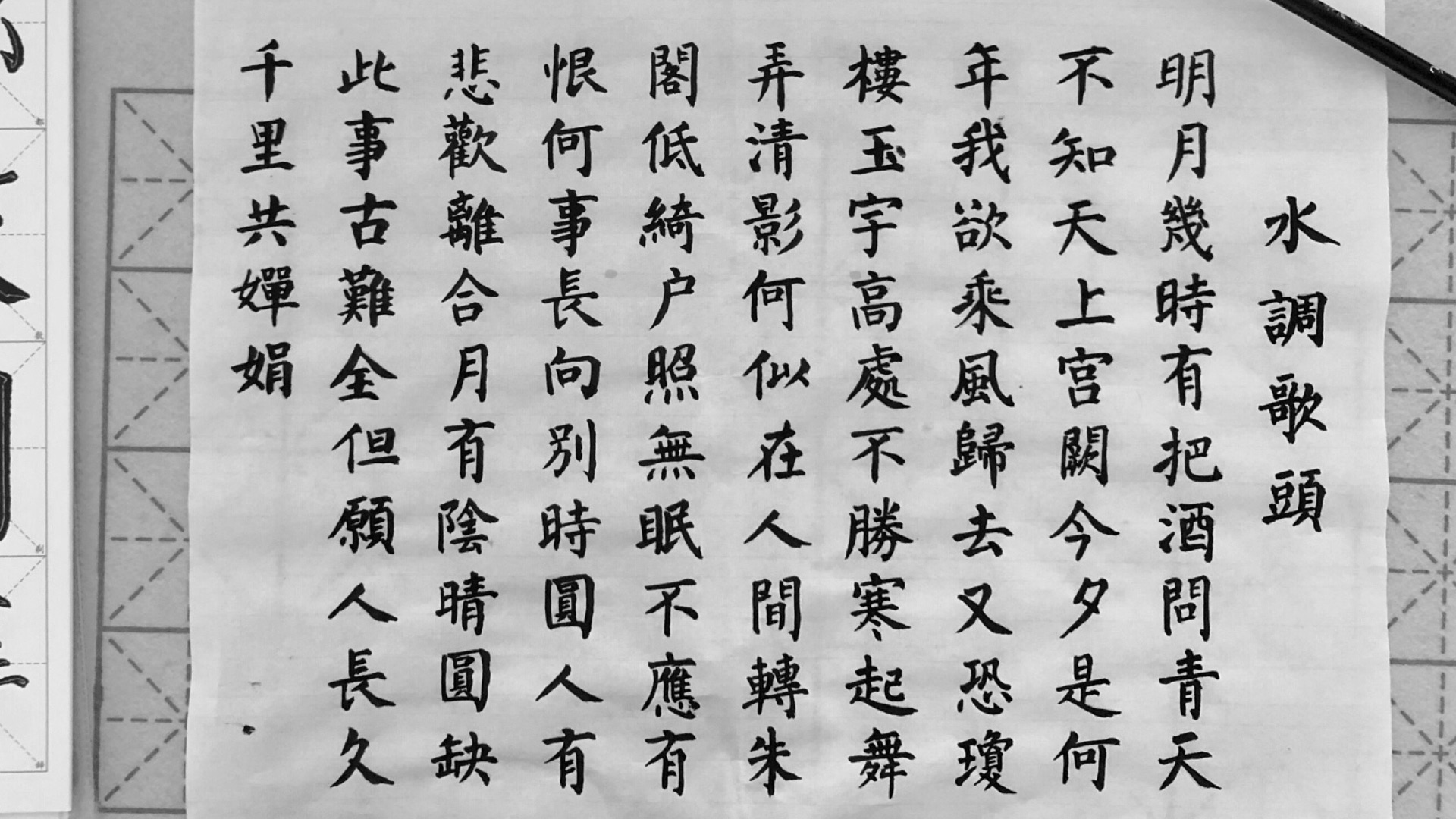

11. Literary Chinese Dominated Formal Writing Until the Early 20th Century

Literary Chinese remained the dominant style of official and scholarly writing in imperial China until the early 20th century. This mattered because the prestige written style could be quite different from what people actually spoke in daily life. The eventual shift away from that older style is one of the biggest visible breaks in modern Chinese language history.

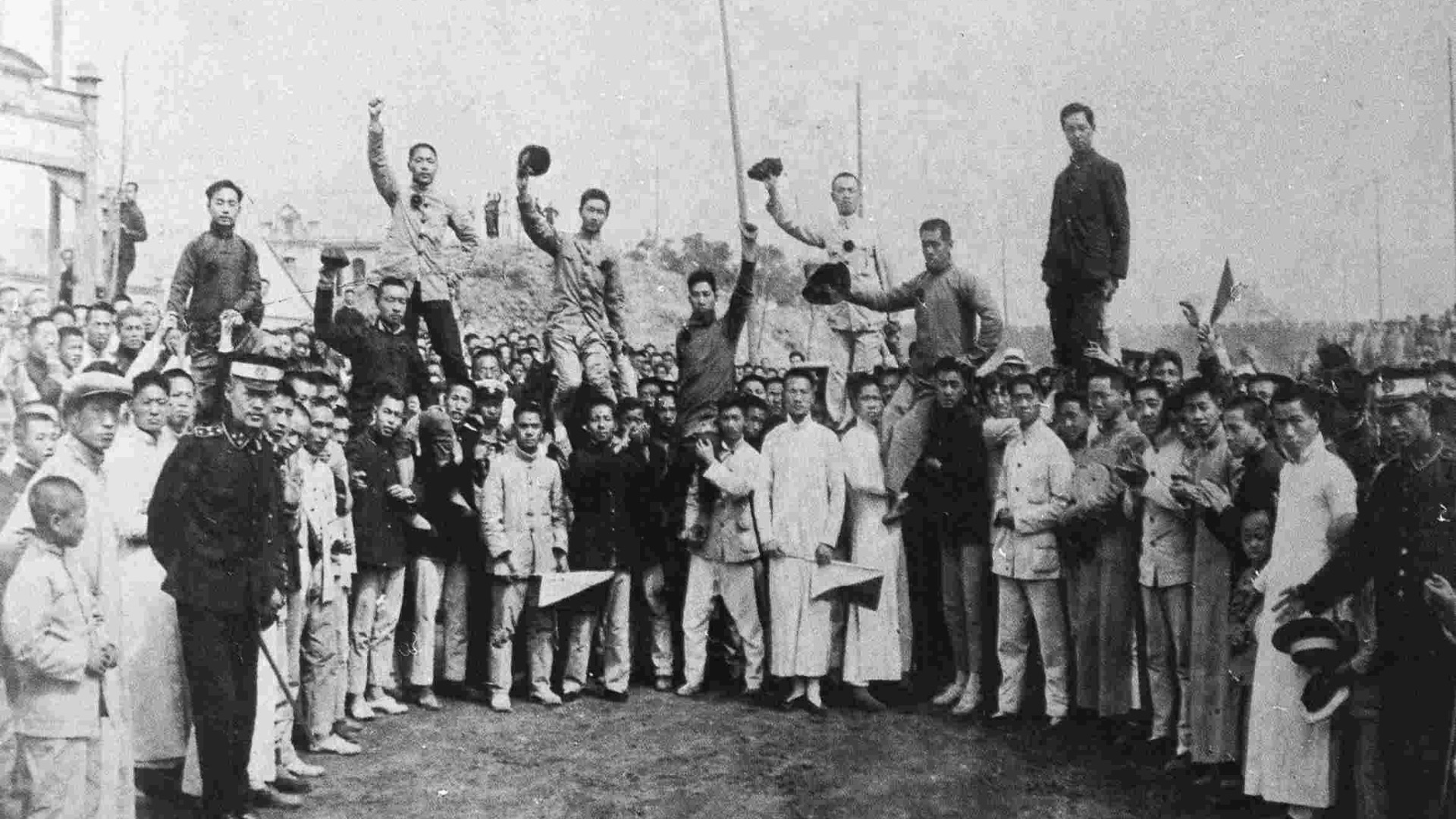

12. The May Fourth Era Pushed Vernacular Writing Into the Center

Reformers associated with the May Fourth period promoted baihua as a modern written style that could replace the 2,000-year-old classical norm, wenyan. Their advocacy made language reform a practical educational issue, not just a literary preference. When you read early 20th-century debates about modernization, the writing-style conflict is often right at the surface.

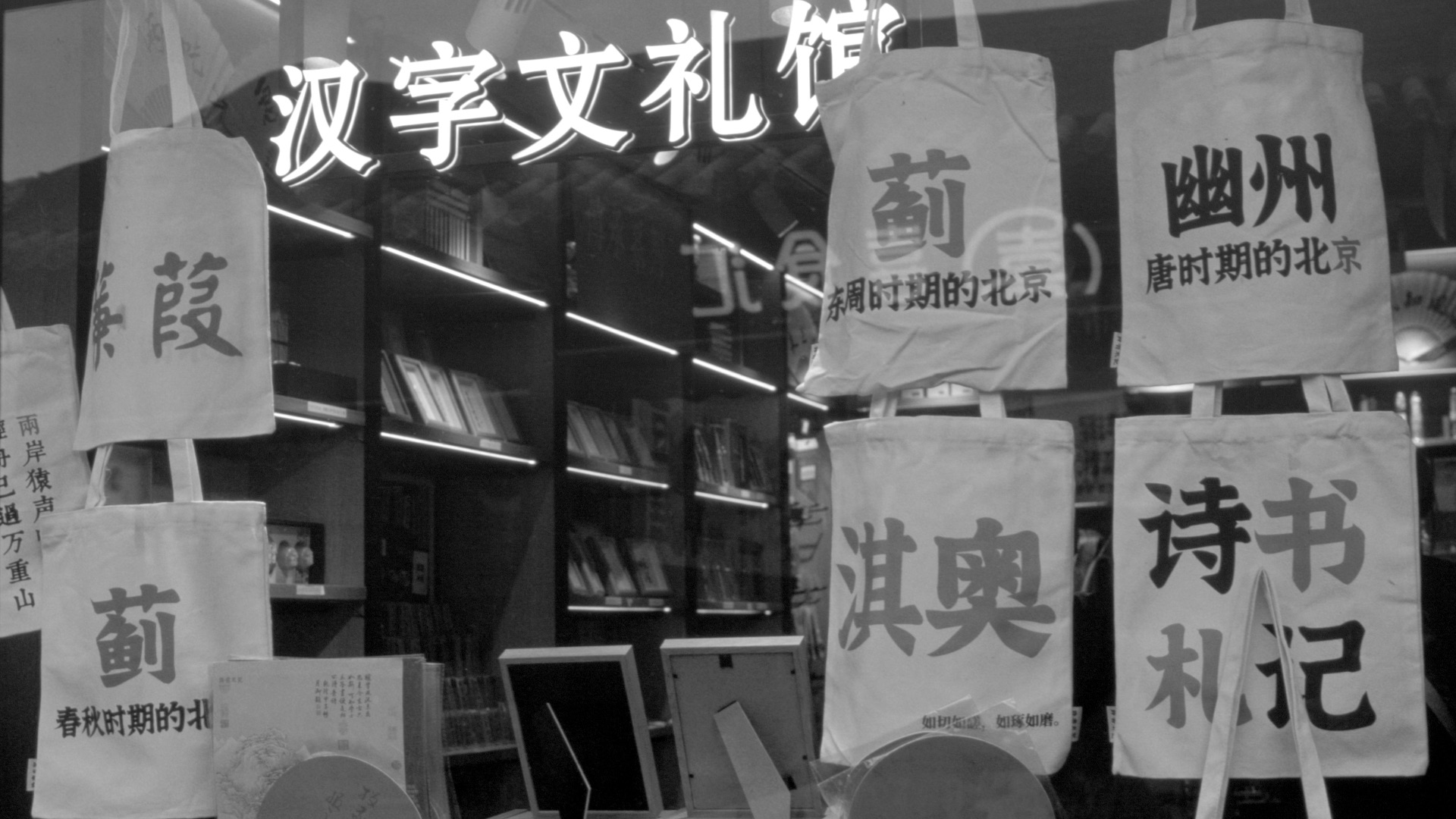

13. Written Vernacular Chinese Became a Shared Medium Across Speech Communities

Written vernacular Chinese (baihua) refers to writing based on spoken varieties, contrasting with the more condensed classical style. Over time, this helped create a common written form that could circulate broadly even when readers spoke different regional varieties at home. It’s one reason modern education and mass media could rely on a more uniform written standard than earlier eras typically allowed.

14. Putonghua Was Defined With a Specific Linguistic Recipe

Putonghua was defined and endorsed in the 1950s with an explicit description tying pronunciation norms to Beijing speech while grounding grammar in northern dialect patterns. That definition matters historically because it neatly states what the “standard” is supposed to be, rather than leaving it as an informal prestige habit. With a definition in place, it becomes much easier for schools, broadcasters, and publishers to enforce consistent standards.

15. Hanyu Pinyin Was Promulgated in 1958 and Became Globally Influential

Hanyu Pinyin was developed in the 1950s and promulgated in 1958 as a standardized romanization system for Standard Chinese. It’s widely used for teaching pronunciation, dictionary ordering, and text input, and it also shaped international spellings of Chinese names and terms. Even if you don’t type in pinyin yourself, you’re likely seeing its conventions whenever Chinese is written in the Latin alphabet.

16. Simplified Characters Were Codified Through Mid-20th-Century Lists

The PRC promulgated a character simplification scheme in 1956, and later published the General List of Simplified Chinese Characters in 1964 as a major standard reference. These documents are central to the modern script history because they formalized what counts as simplified in a way that education and publishing could implement. The details are often debated, but the timeline and the role of official lists are well documented.

17. “Chinese” Spoken Forms Are Commonly Treated as a Cluster of Sinitic Varieties

Linguists often describe the Sinitic branch as containing multiple major groups, and classifications commonly list categories such as Mandarin, Yue, Wu, Min, Hakka, Xiang, Gan, and others. Mutual intelligibility can be limited between some varieties, which is why the label “Chinese” can hide a lot of linguistic diversity. When you separate the writing system from speech, this diversity becomes much easier to understand historically.

18. Sino-Xenic Borrowings Spread Chinese Vocabulary Across East Asia

Sino-Xenic vocabularies refer to large-scale, systematic borrowing of Chinese-origin words into Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese. These layers are historically useful because they reflect conscious attempts to approximate older Chinese sounds when reading Classical Chinese. Linguists still use these patterns when reconstructing historical pronunciation and tracking sound correspondences.

19. Buddhist Translation Helped Expand Specialized Vocabulary and Styles

The long history of translating Buddhist scriptures into Chinese created pressures to represent new concepts and technical terms in readable forms. Modern scholarship often examines the lexical and syntactic features of “Buddhist Chinese” in translated texts, treating it as a distinctive register with measurable language effects. If you’re trying to see how Chinese adapted to new intellectual traditions, these translation corpora are among the most studied examples.

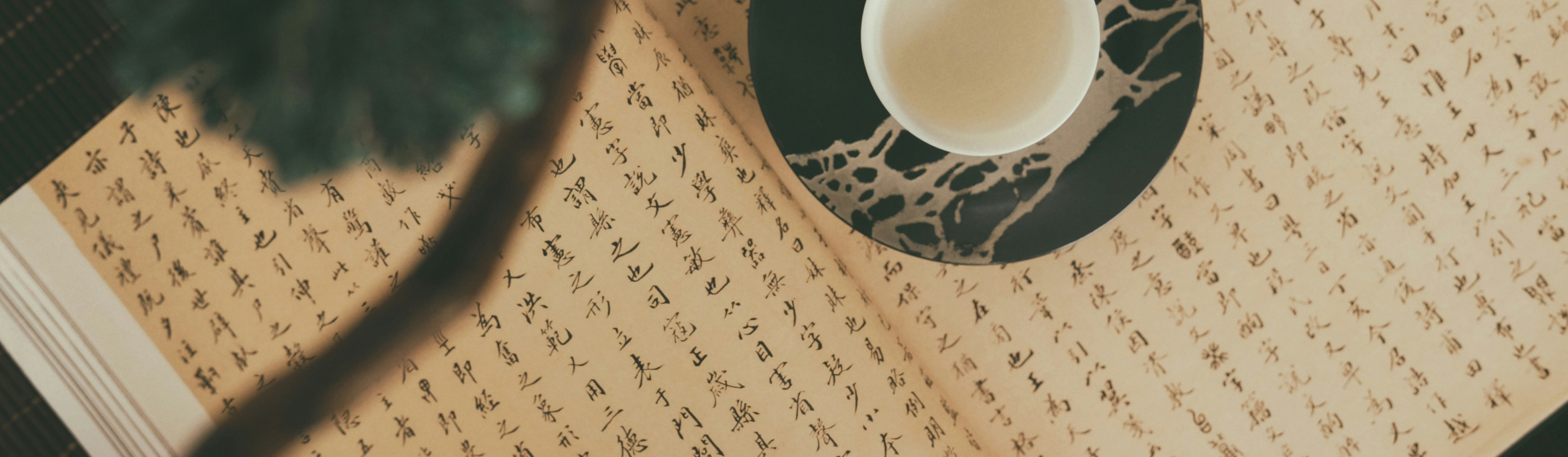

Jose Luis Sanchez Pereyra on Unsplash

Jose Luis Sanchez Pereyra on Unsplash

20. Modern Punctuation Became Mandatory Only in the 20th Century

For much of history, texts were transmitted without mandatory punctuation, and readers relied on conventions or later scholarly marks rather than fixed symbols. Western-style punctuation influenced modern reforms, and mandatory punctuation norms became part of 20th-century standardization in written Chinese. This change altered how texts were formatted and taught, especially in modern publishing and schooling.

KEEP ON READING

20 Powerful Ancient Egyptian Gods That Were Worshipped

Unique Religious Figures in Ancient Egypt. While most people are…

By Cathy Liu Nov 27, 2024

The 10 Scariest Dinosaurs From The Mesozoic Era & The…

The Largest Creatures To Roam The Earth. It can be…

By Cathy Liu Nov 28, 2024

The 20 Most Stunning Ancient Greek Landmarks

Ancient Greek Sites To Witness With Your Own Eyes. For…

By Cathy Liu Dec 2, 2024

10 Historical Villains Who Weren't THAT Bad

Sometimes people end up getting a worse reputation than they…

By Robbie Woods Dec 3, 2024

One Tiny Mistake Exposed A $3 Billion Heist

While still in college, Jimmy Zhong discovered a loophole that…

By Robbie Woods Dec 3, 2024

30 Lost Treasures That Vanished From History

Buried treasure, missing artefacts, legends of ancient gold in them…

By Robbie Woods Dec 3, 2024